What Does the Future Hold

North Korea, Russia, China, India, Brazil, Space...We are at the very beginning of time for the human race. It is not unreasonable that we grapple with problems. - Richard P Feynman

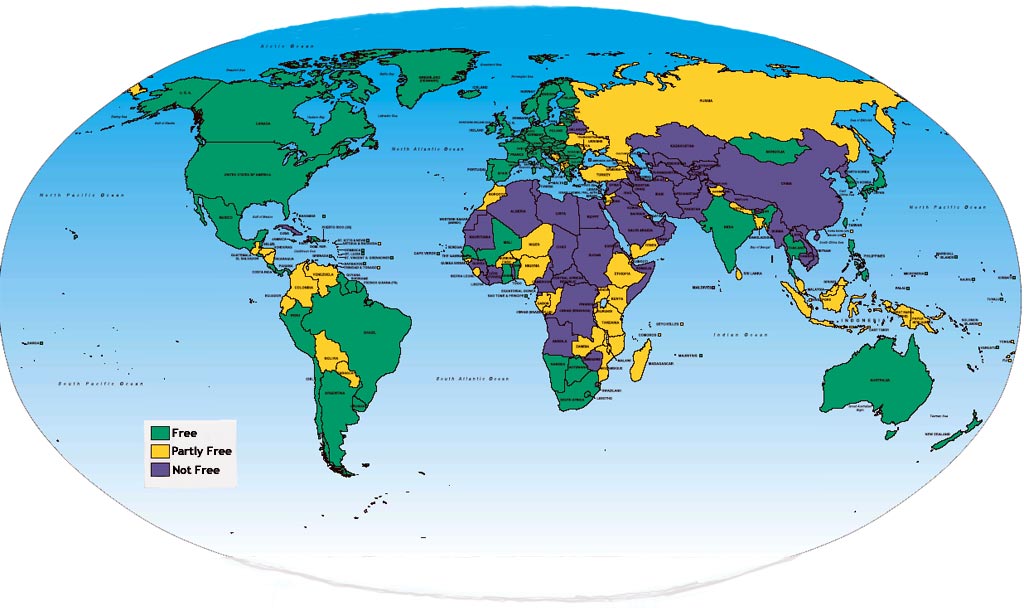

Freedom Today This Map of Freedom reflects the findings of Freedom House's 2004 survey "Freedom in the World", an annual effort that measures gains and losses for political rights and civil liberties in 192 countries and 18 related and disputed territories. In free countries, citizens enjoy a high degree of political and civil freedom. Partly Free countries have some restrictions, often in the context of corruption, weak rule of law, ethnic strife or civil war. In Not Free countries the political process is tightly controlled and basic freedoms are denied. In 2003, there were 2.78 billion people living in Free societies representing 44% of the world's population. There were 1.32 billion people living in Partly Free societies, representing 21% of the world's population. There were 2.21 billion people living in Not Free societies representing 35% of the world's population. Global Trends

Source: freedomhouse.org

The Essential Vladimir PutinA Semi-Authoritarian Present is Russia’s Best Hope for a Liberal Futureby Anatol Lieven

Consider, for a moment, if Putin were to fail. There is no Thomas Jefferson waiting in the wings. Instead, he would almost certainly be replaced by a figure and a movement that are just as authoritarian but more nationalist, more anti-Western, more populist, and less committed to market reform. A Putin meltdown is not out of the question. He began his term with the disastrous decision to reoccupy Chechnya. He may now be moving toward a second blunder, if there is any truth to rumours in Moscow about a future abolition of Russia’s autonomous ethnic republics. Still, the West should wish him well. Why do so many in the West have such a naive faith in Russia’s prospects for rapid reform? The persistent belief that Russia will wake up to free-market democracy is rooted in the success of the former Communist states of Central and Eastern Europe. But the analogy is a faulty one. Compared to Russia, those countries are small and ethnically homogeneous. Russia is a vast fragment of a former empire, and it continues to embrace large, traditional, and impoverished Muslim populations in the North Caucasus. The European successor governments could fall back on pre-Communist statehood and economics. In Russia, Stalinism lasted far longer and was imposed on a far less developed population. The burgeoning nationalism and desire to escape Russian domination in Central and Eastern Europe impelled these states in the direction of NATO and the European Union, enabling their governments to push through deeply unpopular economic and political reforms. In the Soviet Union — with the exception of the formerly independent Baltic states — the historical, economic, and cultural background was very different. Placed in the context of most former Soviet republics, Russia looks better than average in terms of both development and democracy. It is not just the burden of history that makes hope for a rapid transformation in Russia illusory. The country’s dreadful economic decline, social and moral chaos, and rampant corruption in the 1990s shattered the image of economic reform and democracy for the bulk of the population. By 1996, long before the accession of Putin, the combined vote of the liberal parties was already below 12%. Russia’s first taste of democracy was bitter, and fairly or unfairly, those who championed it have been held responsible for policies that created misery for tens of millions while grotesquely enriching a favoured few. So Russia now has no modern mass democratic parties, and without them, any democracy is likely to be a sham. The inchoate frustration of many ordinary Russians flows either to the worn-out former Communists, or to menacing new groups on the populist right. Like their equivalents elsewhere in the world, these far-right parties do not offer serious alternatives to economic reform and could well act as fronts for oligarchic interests. The combination of economic populism and disgruntled nationalism has little to offer, but it could still be potent. In this environment, no Russian government can mobilise broad support for further economic reform. The bulk of the population would be outraged if asked to make additional sacrifices. The strong popular opposition to the recent radical overhaul of Russia’s system of social subsidies was evidence enough of the limited tolerance for reform. Putin’s popularity ratings suffered a steep drop — as much as 20 percentage points in some polls — as a result of his support for the reform. The move depended on Putin’s willingness and ability to defy public opinion. He will need to be stronger still if he is to take on Russia’s oligarchs, whose rise is probably the worst by-product of Russia’s early introduction to democracy. These magnates have a strong grip on the mass media, judiciary, and large parts of parliament. It’s wishful thinking to believe that a fully democratic and law-abiding government would be able to take the oligarchs down a peg. When observers seek parallels for Russia’s condition, they should look not to Europe but to Latin America and parts of Southeast Asia. There, the appearance of democracy has often masked domination by elites who have plundered the state, obstructed economic reform, and murdered journalists and activists who dared to expose their behaviour. This pattern has, in turn, produced periods of populist backlash, which have damaged prospects for economic growth and democratic consolidation still further. Criticism of Putin, often justified, should be leavened with a recognition that on a number of vital issues, he is still pushing economic reform in the face of the entrenched opposition of powerful elites and public opinion. Putin may be an uncomfortable partner, but the West is unlikely to get a better one. In a generation, things may look more hopeful. If they do, it will be due in large part to Vladimir Putin. Anatol Lieven is a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His latest book is America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004) Source: foreignpolicy.com January/February 2005

Source: sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu Population Density, 1995 UN adjusted data {Robinson Projection}

Urban Geography: Getting off the GroundSatellite Imaging Is Helping to Classify Patterns of Urban GrowthLike a good Impressionist painting, a city often requires a bit of distance before its viewer can get a feel for the whole picture. Terra, the newest earth-science spacecraft launched by NASA, America’s space agency, can provide 700km-worth of distance; and William Stefanov, a geologist at Arizona State University, is using this to develop a better understanding of how people create their cities. At this week’s meeting of the American Geophysical Union, in Boston, Dr Stefanov explained how he used data from a satellite-borne instrument called ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection radiometer) to study 12 cities and to classify their growth patterns. Urban planners have long known that cities have different characteristics, but the view from space makes assessing those characteristics faster and more accurate. Dr Stefanov and his colleagues (or, rather, their computers) looked for the boundaries between densely developed areas, which reflect a lot of light because of all the edges and flat surfaces that people like to create, and those with more vegetation, which appear dark by comparison, as nature prefers curves. By focusing on the edges separating dark from light areas, the researchers classified their dozen cities into three types. Six of them, Baghdad, Baltimore, Istanbul, Lisbon, Puebla and Vancouver, are “centralised”: most of their development is concentrated around a “downtown” area, and there is a gradual fading away from this with distance. Three, Albuquerque, Johannesburg and Phoenix, were “non-centralised”: developed more or less evenly over the entire area, but with an abrupt edge. The other three, Chongqing, Madrid and Riyadh, were a mixture of the two types. Other methods of measuring a city’s composition and growth are less precise and more time-consuming than Dr Stefanov’s. They usually involve a combination of aerial photography, ground measurements and door-to-door canvassing. Because that takes so long, it cannot be done frequently. The data from ASTER provide a relatively simple and much faster alternative. Ultimately, the team plans to study 100 cities over 6 years, to try to work out why different cities grow in the way they do. The hope is to tease out the relative contributions to the process of geography, political history, climate, social structure and economics. Working with local experts in each city should provide some answers — and a better idea of how each Impressionistic dot makes up a part of the whole. Source: The Economist print edition 31 May 2001 © 1995-2001 The Economist Newspaper Group Limited all rights reserved

The Growth of Cities

From decade to decade, the amount of rural land that has been consumed by urbanisation is enormous. Between 1982 and 1992, for instance, 19,000 square miles of otherwise rural cropland and wilderness were developed in the US. This would be the equivalent of converting half of Ohio into one big subdivision in a 10-year period, according to the World Resources Institute. Urbanisation is not just an issue in the United States. Right now, researchers estimate that worldwide movement towards cities is growing at 3 times the rate of population expansion worldwide. Only 33% of the planet's population lived in urban areas 10 years ago. Now that number is up to 50%, and in 10 more years roughly 67% of humanity will live in the cities, the World Resources Institute reports. For interesting perspectives, see Aerial Photos of Mexico and Searching High and Wide - particularly note the satellite photo of the city of London at night.

First Five Years of the Net in the 21st Centuryby Danny Bradbury Just a decade ago, the $3 billion flotation of Netscape signalled the start of the mass internet age. The web has conquered the world - and changed our lives... 2001 - Porn, Worms & Viruses The web's dark side asserted itself. Following the spread of the VBS/Loveletter internet worm in 2001, a spate of other worms were released including Sircam, CodeRed and Klez. Meanwhile, an FBI investigation into pædophile websites identified 250,000 suspected users, including 7,200 in the UK. More than 1,200 people were arrested. Today there are 4.2 million pornographic websites - 12% of all sites.

2002 - Online Relationships Friends Reunited began reconnecting old school friends in 2000, growing from 3,000 members in its first year to 4 million at the start of 2002. Meanwhile, a new generation of social websites including Friendster.com and EveryonesConnected.com developed the theme. Today there are more than 300 such sites, including Google's invitation-only service, Orkut.

2003 - Sound & Pictures Apple launched the iTunes Music Store, selling 20 million copy-protected tracks in 7 months. Microsoft's response - the MSN Music Store - wasn't ready until 2004, but research firm Forrester predicts that by 2008 one third of all music sales will be made online. Digital cameras outsold film cameras in the US for the first time.

2004 - Year of the Blog Although the term "weblog" was coined in 1997, 2004 was the year the blog achieved critical mass. Salam Pax, the "Baghdad blogger", became popular - offering a unique insight into life for ordinary citizens during the Iraq war. AOL began to include blogging tools in the latest versions of its software, while Microsoft launched its MSN Spaces blogging service. Today, there are an estimated 14.7 million blogs, with a new one created every 7.4 seconds.

2005 - Online News Citizen journalists are now appearing daily, not just on the big news sites. Nowpublic.com and Scoopt.com offer people the chance to be photojournalists, while podcasting (a grassroots internet radio movement akin to audio blogging) is hugely popular after just one year. A report by the Carnegie Corporation shows that 18- to 34-year-olds in the US are twice as likely to use an internet portal as a printed newspaper for daily news.

Source: belfasttelegraph.co.uk © 2005 Independent News and Media (NI) The internet years falling in the 20th century may be found in the middle of the 2nd page prior to this one.

2050 - and Immortality Is within Our Graspby David Smith Aeroplanes will be too afraid to crash, yoghurts will wish you good morning before being eaten and human consciousness will be stored on supercomputers, promising immortality for all - though it will help to be rich. These fantastic claims are not made by a science fiction writer or a crystal ball-gazing lunatic. They are the deadly earnest predictions of Ian Pearson, head of the futurology unit at British Telecom. "If you draw the timelines, realistically by 2050 we would expect to be able to download your mind into a machine, so when you die it's not a major career problem," Pearson said. "If you're rich enough then by 2050 it's feasible. If you're poor you'll probably have to wait until 2075 or 2080 when it's routine. We are very serious about it. That's how fast this technology is moving: 45 years is a hell of a long time in IT." Pearson, 44, has formed his mind-boggling vision of the future after graduating in applied mathematics and theoretical physics, spending 4 years working in missile design and the past 20 years working in optical networks, broadband network evolution and cybernetics in British Telecom's laboratories. He admits his prophecies are both "very exciting" and "very scary." He believes that today's youngsters may never have to die, and points to the rapid advances in computing power demonstrated last week, when Sony released the first details of its PlayStation 3. It is 35 times more powerful than previous games consoles. "The new PlayStation is 1% as powerful as a human brain," he said. "It is into supercomputer status compared to 10 years ago. PlayStation 5 will probably be as powerful as the human brain." The world's fastest computer, IBM's BlueGene, can perform 70.72 trillion calculations per second (teraflops) and is accelerating all the time. But anyone who believes in the uniqueness of consciousness or the soul will find Pearson's next suggestion hard to swallow. "We're already looking at how you might structure a computer that could possibly become conscious. There are quite a lot of us now who believe it's entirely feasible. We don't know how to do it yet but we've begun looking in the same directions, for example at the techniques we think that consciousness is based on: information comes in from the outside world but also from other parts of your brain and each part processes it on an internal sensing basis. Consciousness is just another sense, effectively, and that's what we're trying to design in a computer. Not everyone agrees, but it's my conclusion that it is possible to make a conscious computer with superhuman levels of intelligence before 2020." He continued: "It would definitely have emotions - that's one of the primary reasons for doing it. If I'm on an aeroplane I want the computer to be more terrified of crashing than I am so it does everything to stay in the air until it's supposed to be on the ground. You can also start automating an awful lots of jobs. Instead of phoning up a call centre and getting a machine that says, 'Type 1 for this and 2 for that and 3 for the other,' if you had machine personalities you could have any number of call staff, so you can be dealt with without ever waiting in a queue at a call centre again." Pearson, from Whitehaven in Cumbria, collaborates on technology with some developers and keeps a watching brief on advances around the world. He concedes the need to debate the implications of progress. "You need a completely global debate. Whether we should be building machines as smart as people is a really big one. Whether we should be allowed to modify bacteria to assemble electronic circuitry and make themselves smart is already being researched. We can already use DNA, for example, to make electronic circuits so it's possible to think of a smart yoghurt some time after 2020 or 2025, where the yoghurt has got a whole stack of electronics in every single bacterium. You could have a conversation with your strawberry yogurt before you eat it." In the shorter term, Pearson identifies the next phase of progress as Ambient Intelligence: chips with everything. He explained: "For example, if you have a pollen count sensor in your car you take some antihistamine before you get out. Chips will come small enough that you can start impregnating them into the skin. We're talking about video tattoos as very, very thin sheets of polymer that you just literally stick on to the skin and they stay there for several days. You could even build in cellphones and connect it to the network, use it as a video phone and download videos or receive emails." Philips, the electronics giant, is developing the world's first rollable display which is just a millimetre thick and has a 12.5cm screen which can be wrapped around the arm. It expects to start production within 2 years. The next age, Pearson predicts, will be that of Simplicity in around 2013 - 2015. "This is where the IT has actually become mature enough that people will be able to drive it without having to go on a training course. Forget this notion that you have to have one single chip in the computer which does everything. Why not just get a stack of little self-organising chips in a box and they'll hook up and do it themselves? It won't be able to get any viruses because most of the operating system will be stored in hardware which the hackers can't write to. If your machine starts going wrong, you just push a button and it's reset to the factory setting." Pearson's third age is Virtual Worlds in around 2020. "We will spend a lot of time in virtual space, using high quality, 3D, immersive, computer generated environments to socialise and do business in. When technology gives you a life-size 3D image and the links to your nervous system allow you to shake hands, it's like being in the other person's office. It's impossible to believe that won't be the normal way of communicating." Source: observer.guardian.co.uk The Observer Sunday 22 May 2005

The Privacy of the Unknown Citizen

Original photo source: metmuseum.org In this Information Age, government computers contain vast amounts of information, gleaned from innumerable sources, on virtually every citizen. Privacy could, in theory, be impossible. Yet most citizens retain a tolerable level of privacy because correlating information from myriad sources into a meaningful picture takes money and time, and is not likely to be undertaken when a citizen does nothing out of the ordinary. Two important questions with regard to privacy today are: How is privacy eroded? What is the cost to an individual to remain “ordinary”, thus avoiding excessive government scrutiny? Privacy erosion in the United States begins at birth; each child receives a social security number within days. Most insurance companies use this number to amass health data, including records on immunizations, blood type, diseases, and even, in some cases, fingerprints and genetic code. When the child begins school, information-gathering is stepped up. Public education during the past 30 years has tended against testing elementary school children for knowledge of content, instead emphasising psychological assessment and ability to conform to the group. Whilst a "test" is an objective measure of a child's ability to solve a problem, an "assessment" is a social scientist's speculation about the environmental conditioning of the child. As an example, in W H Auden’s poem "The Unknown Citizen", the government made several assessments of ordinary citizen JS/07/M/378 before erecting a marble monument in his honour. Since the 1980s, the Educational Quality Assessment, used in Pennsylvania and seven other states, has asked students about attitudes, worldviews, and opinions, mostly via hypothetical situations and self-reports. The EQA tells educators it is seeking the student's "locus of control" and determining whether he will "conform to group goals." After graduating and getting a job, employers’ personnel departments pick up where the schools left off, checking their employees’ credit, health, driving and police records. Merchants, through “loyalty cards”, amass detailed records of individual buying habits and can provide insurers (and, when necessary, the IRS and police) data on alcohol, cigarette, candy, red meat, prescription drug and adult diaper purchases (among other embarrassing revelations). Cross-matching, information-sharing and data-trafficking capabilities allow for comprehensive consumer profiling. On the other hand, information is a commodity with a cost. If no flag is raised, no one is likely to assemble the information amassed on a particular person. Children can be home schooled. Employees can keep their heads down at work, pick no fights, be punctual, hardworking, and seldom absent. Purchases can be made in cash and the discounts that use of loyalty cards brings can be forgone. Careful driving, no arrests, no phone calls to drug dealers, and bills paid mostly on time assist an individual in staying relatively invisible. But this invisibility has a price. No protest marches, no civil disobedience, no fiery letters to editors, no splashy lawsuits, no subversive poetry, no visiting dissidents’ websites, and no political careers are wise as these actions reduce privacy. However, such actions also bring colour to life. Unfortunately, more colour means more celebrity. Pop star Michael Jackson, the late Princess Diana, and presidential paramour Monica Lewinsky are examples of colourful celebrity extremes who lost virtually all privacy and incurred a great deal of government scrutiny by becoming exceedingly publicly visible. None were known to particularly relish the total loss of privacy. But all were financially compensated in some measure. Conversely, some individuals, such as Mark Chapman, murderer of popular singer/songwriter John Lennon, and Charles Manson, mastermind of the Tate/La Bianca murders and leader of a demented group called The Family, voluntarily opt for public attention and celebrity without sufficient talent to achieve it in a positive way. Until they became murderers, these two were essentially invisible. Now, they are notorious. Each has websites and fan clubs and, if allowed, could earn huge sums by writing books and appearing in movies. But they are not allowed – each is incarcerated, probably for life. Not “making waves” means a citizen will probably be able to maintain a comfortable degree of privacy despite the intrusion of computerised government record-keeping. However, this privacy may ultimately be purchased at tremendous cost, as it may preclude the achievement of a life of excellence by curbing curiosity and limiting exploration. Maintaining an “ordinary” interface to the world could cause scholarships to be forfeited, income to be reduced (perhaps by a considerable amount) and pride and a sense of self-worth to be abridged, thus impacting lifetime happiness. Some people will find the cost intolerable and may attempt, through flamboyant or criminal behaviour, to ensure they are noticed, regardless of consequence. Are the rest free? Are they happy? The question is absurd: had anything been wrong, we should certainly have heard.

For more on modern history including both widely-known and little-known facts, opinions (mine and others), a few political cartoons, some photos, a map or two, rants, politicians,

geology, speculation and more, click the "Up" button below to take you to the Index for this History section. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment

In the West, hostility toward Russian

President Vladimir Putin (right) stems from two beliefs: that Russia should move quickly toward Western-style democracy and that there is a strong, popular, liberal opposition ready to lead

such a transformation. The first is mistaken, the second, pure fantasy. It will take at least a generation for Russia to build the foundation for a modern market economy

and democracy. It’s an uncomfortable reality, but, for the foreseeable future, only a semi-authoritarian government such as Putin’s can keep Russia moving in the right

direction. If Putin weren’t there, we’d soon miss him.

In the West, hostility toward Russian

President Vladimir Putin (right) stems from two beliefs: that Russia should move quickly toward Western-style democracy and that there is a strong, popular, liberal opposition ready to lead

such a transformation. The first is mistaken, the second, pure fantasy. It will take at least a generation for Russia to build the foundation for a modern market economy

and democracy. It’s an uncomfortable reality, but, for the foreseeable future, only a semi-authoritarian government such as Putin’s can keep Russia moving in the right

direction. If Putin weren’t there, we’d soon miss him.