Money and Power: These Mean War

Humans Can Be So RevoltingEvery new society is soon in need of a graveyard and a prison. - Nathaniel Hawthorne European wars, especially between those between Britain and France, were generally over commercial rivalry. The American and French Revolutions were outgrowths of the conflicts of the Seven Years War (1754 - 1763) (also called the French and Indian War) - which, despite its name, was not the French fighting the Indians (or even the Native Americans) but was the French once more fighting the British. Revolution in AmericaThe first 2 years of this 9-years-long war were a state of undeclared fighting, so it ended up (inaccurately) just being called the Seven Years War. During this time, Spain was not a leading power - and become even more diminished as time progressed. At this time, Spain owned Florida, Mexico and South America. France owned Quebec and Louisiana. Britain owned the 13 colonies – though smaller than the other countries’ holdings, these had a greater population (at least of Europeans - see "The Imperial Slaughterhouse" below for more on the diseases Europeans took with them wherever they went). Canada was only very sparsely populated at this time. The British felt that their colonies were an extension of their homeland, whereas the French were still going through the Mercantilist period - they felt that they should import nothing, so their holdings in North America were purely for resource gathering of raw materials.

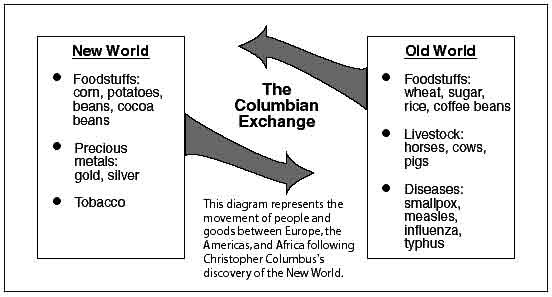

The Columbian Exchange The fighting between the French and the British began over a dispute about the Ohio River Valley region - the boundary was not clearly established. Colonel George Washington was in charge of defending Virginia for the British. Washington tried to settle a conflict over a piece of property on the border; fighting broke out and the French leader was killed. This was the opening salvo of the war. In 1759, British General Wolf captured Quebec. In 1760 Montreal fell. After that, the Peace Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763. France gave up all of Canada to the British. They also decided to give their Louisiana Territory to Spain as they wished to become allies. Spain had lost Florida to the British, so the Louisiana Territory was sort of a peace offering. The end result was that France lost its presence in North America entirely except for a few of the Caribbean islands. In the end, Britain emerged as the predominant power. This set the stage for the American Revolution - since the French were gone, the colonists no longer needed help from Britain to protect them from the world’s most dynamic fighting force – the French. Also, after 150 years of settlement in America, the colonists had built a separate identity and no longer closely resembled the British. At least 1/3 of the Americans weren’t even British. Americans now traded with other countries and had their own legislative bodies. They felt in charge of their own destiny.

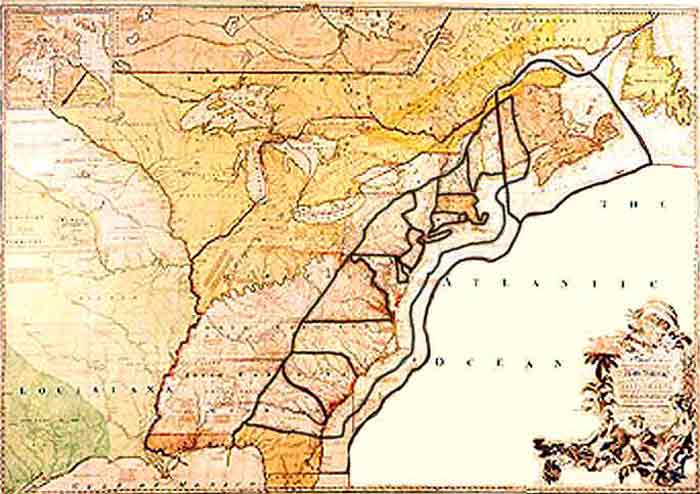

Map of the 13 Original Colonies Made in 1755 (Library of Congress) The Enlightenment had brought new ideas regarding “Natural Law.” Americans now felt they had a right to oppose any monarch who overstepped his authority. They felt they had a right to better than second-rate status, which is what Britain was assigning them. Also, the colonists had a strong frontier mentality and, due to all that undeveloped land, they were ready to expand westward. However, Britain felt that there were too many hostile natives (many tribes had earlier sided with the French); Britain passed a proclamation forbidding exploration – the new territory was off limits. This offended American colonists, as they wished to claim this land. Another major factor was the Stamp Act. Britain was far in debt (roughly £150 million) due to the expense of fighting the Seven Years’ War, and they felt that since the war benefited the colonists, the colonists should pay for it. They decided that a means to get the money was through a tax. The Stamp Act stated that all papers flowing through the colonies had to have a stamp on it proving it had been paid for – this even included decks of playing cards. Outrage followed as this had never before been done before in the 150 years that the colonies had been established. The British heretofore had maintained a hands-off policy, especially on taxes. Now the Brits were acting like parents, not partners. It wasn’t the money that rankled so much as the relationship. The American people felt that taxes were something that only their own leaders should collect. They felt that the British had no right to impose ANY taxes on them, much less levy something so drastic as the Stamp Act. They didn't so much mind paying the money, but they felt their own legislative branches should have handled its imposition and collection. Soon, tax enforcers found themselves subject to mob violence; they were frequently tarred and feathered. While it was Parliament, not King George, who was to blame, sometimes King George was the brunt of ill-will. After a few years, Britain realised the Stamp Act wasn’t actually bringing any money into their coffers, so they repealed it. This fixed nothing, however, because they made it clear to the colonists that the law was only repealed it because it wasn’t generating enough. They still maintained that they had the RIGHT to levy whatever taxes they chose - and, in fact, they did levy more taxes, which were met with the same results - mob violence, speeches, philosophes circulating propoganda, et cetera. Next came the Tea Act, which the British imposed to cease the smuggling of Dutch Tea and force the colonies to buy British tea. This culminated in 1773 in an act of rebellion called the Boston Tea Party. Americans stormed British boats and dumped all the tea into the Boston Harbor. This would have been a good time for Britain to drive a wedge in between Americans because sentiment was divided at this point as the Boston Tea Party had taken protest to an extreme. However, the Brits react badly: they closed the Port of Boston and demanded total compensation. They instigated the Intolerable Acts demanding restitution; they stripped the state of Massachusetts of its right to govern after deciding that that state was the protagonist. They forbade citizens to meet in public spaces and stated that British troops would quarter themselves in private homes - by force if necessary. All this led to a meeting in Philadelphia which came to be called the First Continental Congress. There, they decided to boycott all British products. A plea was forwarded to King George, but he ignored them. By 1775, the first open conflict occurred. At Lexington and at Concord, there were a clashes between British troops and American soldiers (called "Minute Men" because they could be ready to fight in a minute). The first shot was fired at Lexington – it later came to be called “the shot heard ‘round the world.” A year later, America finally declared her independence. (Thomas Paine’s book Common Sense was influential in causing this decision to be reached.) Finally, in a unanimous vote (with the exception of New York, who abstained), the Continental Congress approved separation. On 7 June 1776 Richard Lee stood up in congress and uttered a resolution that forever changed the course of American History.

This resolution set a chain of events into action that would led to the writing of the Declaration of Independence (drafted by Thomas Jefferson) and finally to its adoption, and to American Independence on 4 July 1776. It is interesting that Jefferson, an Enlightenment thinker, applied the thinking of John Locke in that he blamed King George III for everything, not Parliament – America declared that Parliament had no authority over them - this was because the idea of Natural Law - that all are entitled to Life, Liberty, and Property - superseded all monarchal power and if a monarch violated this precept, it was right that he or she be overthrown. The first draft of the Constitution contained a ban against slavery, but this was dropped later so as not to offend the Southern states. Once the Declaration was signed, America received a major boost after the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, and as a result, managed to convince France to provide them with aid. The French were still sore about the Seven Years’ War, saw that the Americans were winning, and decided to go along with them so that they would remain allies in the future. Under Louis XVI, the French provided funds and troops. At the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, the French provided naval support in the form of a blockade, preventing British forces there from getting re-enforcements of troops and supplies. This allowed George Washington to trap the British garrison at Yorktown, Virginia. British merchants began to urge that the war be over so that trade with the colonists could resume. Finally, the British pulled out, and in two years, another Treaty of Paris was signed (this one in 1783). Independence was granted to America and they were given control of all land west to the Mississippi boundary.

Territorial Growth of the US America still faced a problem, however, as they had to decide what kind of government they needed – would more power reside with the Federal government or

with the state government? They needed a central governing authority now that the King was gone. This was met with a lot of controversy. Finally, they decided

to have a weak central government primarily aimed at national defence. This was outlined in a document called the Articles of

Confederation. But this didn’t really solve enough problems and things still weren’t working. The states lacked standardisation, making travel and trade more

difficult. So the Constitutional Convention was held to come up with something new. Out of that came the Constitution, a masterly

compromise. It stated that there would be a strong central government, but its powers were limited to those specifically stated.

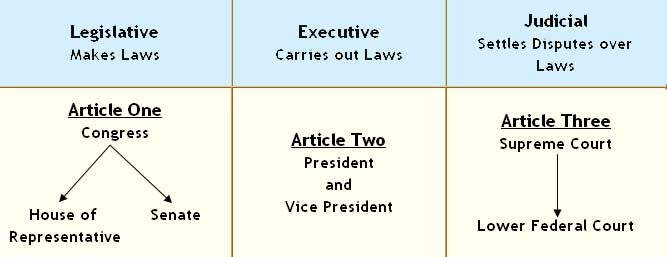

Branches of Government Established by the US Constitution The constitution was the work really of two men: Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison. Hamilton was an aristocrat who always looked down upon the "uneducated classes" and thought only the elites were able to adequately govern. (See A Teensy Piece of History for a tidbit on Hamilton.) He would probably not have been opposed to a monarchy. However, he was counterbalanced by James Madison, who was a follower of the Enlightenment thinkers, and felt that you really should give power to the people. He felt that they could have a strong central government, but that it could be a Republic. This went against 2000 years of history, as no working form of government, apart from monarchies, had ever existed for such a large nation. Madison felt that the old notion of it being impossible to have a Republic for such a large country was just wrong. To prove this, he pointed to other philosophers, such as David Hume, a Scottish philosopher, who felt that, as long as there were sufficient checks and balances, competing factions and interests would cancel each other out, causing everyone to work together. (The electoral college is the primary reason the US can be called both a Republic and a Democracy.) Finally, the system in use today came about, with only slavery left to work out. Interestingly, American political parties evolved out of a split in public opinion over the French Revolution. Revolution in FranceThe road to revolution in France was not nearly as (relatively) peaceful as in the US. It was long, bloody, and did not result in anything quite so concrete or positive being decided. There were three main causes of the revolution:

During the reign of Louis XV (Louis XIV’s great-grandson), most of Frances’ wealth came from trade. This caused the port cities to get all the money, and so the non-coastal cities were back in the dark ages and never saw any reward for their labour. Louis XV reigned for 60 years. He was seen as weak and easily manipulated. (For example, he had a mistress who exerted power publicly and made him lose face.) His poor personality and public image caused a decline in the idealism that characterised the Age of Absolutism. He died in 1774. His most famous quote was, “After me, the deluge.” (He was right about that.) Louis XVI was Louis XV’s grandson. He was the one who helped the nascent America during their revolution – which had seemed like a good investment at the time, but it put a real strain on the French economy, which was already performing badly. On top of this, France was squabbling with Russia, and Louis' wife, Marie-Antoinette, was from Austria, a supporter of Russia. Deteriorating economic conditions caused things to come to a head, finally leading to the French Revolution. Since the country was broke, Louis had decided to raise taxes. Of the Three Estates, he exempted the First Estate (the Clergy) and the Second Estate (the Nobility) from taxation. Only the Third Estate (the peasants and the bourgeoisie or merchant class) was left to shoulder the increasingly heavy tax burden. Since the Third Estate comprised 80 - 90% of the population, the time was ripe for revolution. Versailles went from being a source of pride to being seen as a symbol of decadence. There were outbreaks of violence, and many places refused to pay the taxes which had been imposed. The Absolute Monarchy was no longer holding together. Louis responded by reinstating an old idea, namely the Estates General, an organisation of elected representatives designed to reduce royal power. It had not met in 175 years when it was called on to meet once more at Versailles. All Estates had their representatives; however, as so much time had passed, there was quarreling over the exact etiquette that should be followed. If each Estate got one vote, the Third Estate would always be overruled, even though they represented the vast majority of the people. So the Third Estate recommended one person, one vote. This reform was blocked, however, so the Third Estate broke off and changed its name to the National Assembly. Three days later, officials at Versailles locked them out of their meeting place. In defiance, the National Assembly met in a nearby indoor tennis court and produced the Tennis Court Oath. This oath stated that members needed to stick together, to continue meeting until they got their way. They felt that the sovereignty of the people resided in the people themselves and in their elected representatives. A resolution was issued which stated that sovereignty had been moved from the king to the people. One week later, Louis XVI stated that he would allow the Assembly to meet together to hammer out a constitution. This was seen as an initial victory for the peasants and this encouraged the people. The masses in Paris felt that since they had won a concession, they needed to take action to ensure future victories. Apparently, they decided one such action was to storm The Bastille, an armory, presumably to seize the arms so that they couldn’t be used against the people. This act turned out to be mainly symbolic because there were no arms to speak of in the Bastille to seize and there were only about 6 prisoners at that time. The action was bloody, but the peasants won. Oddly, they felt they had somehow finally been freed (but the worst was yet to come). Immediately, some of the onerous taxes were repealed. After some debate, the National Assembly came up with the Declaration of the Rights of Man (Thomas Paine contributed to this). Some of the key features were that "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights," "Mankind's natural rights, are Liberty, Property, Security, and Resistance to Oppression" and "Every man is assumed innocent until proven guilty." There were also some freedom of expression clauses and assurances of representative forms of government. There was pressure during the writing of the declaration for the rights to apply to women as well (they were intended only for men). So women were given the right to divorce and to hold property - but not to vote nor to hold office.

Eventually, Louis realised that he would be in grave danger if he did not acquiesce, and so he agreed to a constitutional monarchy. However, he took several months to decide this, and that was a little too long - mobs were taking matters into their own hands, palace guards were killed, and finally Louis and his family were temporarily taken to Paris for their safety, where they were held virtually as prisoners. Due to the anarchy breaking out, mobs were common, and a war with Britain somehow started. Things were spiraling out of control. At this point came the ascendancy of Napoléon Bonaparte. The French Revolution was a bit more desperate than the American one. The Americans weren’t trying to overthrow the British style of government – they just wanted to return to the laissez faire policy they thought had existed in the past. Plus, America was wealthy – they were not starving. They were less heavy-handed in their reforms. They did not really have to overthrow a preexisting government, and the Enlightenment figures in America were a lot more passive. In France, the peasants and the philosophes did not always agree, though they thought they did at first. France was plagued by misunderstandings, incompetence, impatience, and greed. France looked to America for guidance.

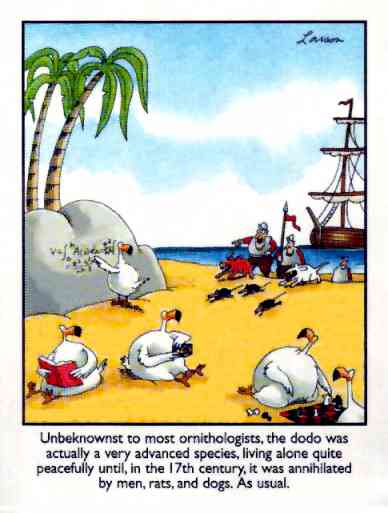

The Imperial SlaughterhouseNature [is] that lovely lady to whom we owe polio, leprosy, smallpox, syphilis, tuberculosis, cancer. - Dr Stanley N Cohen Romanticism and Colonial Disease by Alan Bewell Living as we do in an era of the "globalisation of disease", threatened by new killer viruses jetting around the world, we have become more aware of the role of disease in shaping human history. And in no sphere is that more evident than in the blood-drenched chronicles of imperialism. Wherever Europeans went, they brought ghastly epidemics - smallpox, typhus, tuberculosis - to virgin populations entirely lacking resistance. The results were devastating. During the century following Christopher Columbus, in many zones of the New World up to 90% of the indigenous population was wiped out - germs were far more lethal than guns in expediting the work of conquest. Over the course of the next three centuries, some 20 million slaves then had to be shipped to the Americas to fill the labour vacuum, and they in turn brought in their wake the characteristic African diseases of malaria and yellow fever. It would be a mistake for us to assume that our post-colonial times are the first to appreciate the medical disasters wrought by empire-building. Compassionate contemporaries were under no illusions, as Alan Bewell stresses in his skilfully written, cross-disciplinary book. "Wherever the European has trod, death seems to pursue the aboriginal," rued the sensitive young Charles Darwin in his Beagle journal, shortly before the Tasmanian aborigines were driven into extinction, largely by white men's diseases. Particularly sensitive to this melancholy plight were the English Romantics, sympathising with victims and siding with the people against the powerful. The artist and poet William Blake never ceased to expose the plague of empire, and he found worthy successors in Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron, who himself fell victim to fever while fighting on the side of the Greeks against the curse of the Ottoman Empire; and even the increasingly reactionary Samuel Coleridge remained fervent in his hatred of the slave trade. Bewell brings out well the Romantics' dramatic vision of the toll taken by imperial conquest upon the health of all parties. In poetry and prose alike, Romantic circles portrayed the hubris of the colonial slaughterhouse. The health of natives was undermined by settlers' diseases; slaves were brutalised, not least by syphilis passed on by masters' lusts; and Europeans fell like flies themselves, above all, those hard-living and hard-drinking soldiers sent to garrison the outposts of West Africa and the Caribbean. Out of 350 men sent to the Gold Coast in 1782, only seven were alive and on duty three years later. Despatched to quell a slave rebellion on St Domingue, 40,000 French soldiers died, allowing Haiti to come into existence, the first black state in the New World. Like Coleridge in his Rime of the Ancient Mariner, William Wordsworth, too, was particularly effective in conveying the plight of "tropical invalids". Returning from duty overseas, pallid and haggard, their constitutions wrecked, ex-soldiers were treated as pariahs, disowned by all for bearing the stigma of colonial dirty work. It is no accident that it was Mary Shelley who, with the first cholera pandemic approaching, produced in The Last Man (1826) a futuristic novel about the eradication of the entire human race by a new killer plague emerging out of the East, nature's punishment for human vainglory. The tropics also did rhetorical service as a mirror held up to home at a time of industrialisation. The living conditions of the masses in "darkest England" were routinely likened to those of Indian or African natives. "The room of a fever patient, in a small and heated apartment in London, with no perflation of fresh air," opined the sanitary reformer Thomas Southwood Smith, "is perfectly analogous to a stagnant pool in Ethiopia, full of the bodies of dead locusts. The poison generated in both cases is the same." Cholera introduced a terrifying tropical disease into the very homes of the English, the retribution of the Orient. As in the subjugated empire, the disease was widely read as symptomatic of the filth and disorder of the masses, indeed, a manifestation of the "democracy fever" that arose with the Reform Bill of 1832.

Sickness from Abroad: Father Thames Presents His Offspring Perhaps galvanised by putrefaction and pauperism at home, Romantic attitudes to colonial disease were complex. On the one hand there was a pervasive fatalism. With their steamy swamps and rotting vegetation, the tropics were inherently pathogenic, according to the dominant miasmatic theories of disease aetiology set out in James Lind's Essay on the Diseases Incidental to Europeans in Hot Climates (1768) and elsewhere. Sensible diet, lifestyle and "seasoning" (acclimatisation) might reduce the risks, but torrid climes were inevitably white men's graves. Yet Romanticism also possessed a Promethean streak. Through the application of science, energy and will, progress could transform the environment, drain swamps, fell forests, introduce sweet air, and clean up settlements; humanitarianism could make the "heart of darkness" as hygienic as temperate parts. The Romantic dream of environmental transformation thus expressed a noble ideal, not dissimilar to the imperialist "white man's burden". As Bewell insists, these facts require us to abandon any simplistic vision of the Romantics as pure nature-lovers. Readers familiar with this field will find that Romanticism and Colonial Disease sometimes reploughs furrows recently turned by others. Jane Eyre is recycled as an imperial novel, and the ambiguous attitudes of Thomas De Quincey towards the East (it brought cholera and the bitter-sweet opium to which he was addicted) are again discussed. And, strangely for a professional literary critic, Bewell is at his weakest when practising textual criticism, some of his readings being forced or far-fetched. We are told, for instance, that "And gathering swallows twitter in the skies", the evocative final line of John Keats' ode "To Autumn", incorporates a reference to the sore throat from which the poet had been suffering as a result of his encroaching tuberculosis, making swallowing difficult. Readers will surely find that interpretation hard to swallow. Overall, however, this is a confident addition to the growing study of the history of environmental protest. It used to be said that if there was any justification of imperialism, it was the medical benefits it had conferred. As early as the romantics, that could have been dismissed as special pleading. Roy Porter is at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 183 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE, UK Source: Nature Vol 404 23 March 2000

For more on modern history including both widely-known and little-known facts, opinions (mine and others), a few political cartoons, some photos, a map or two, rants, politicians, geology, speculation and

more, click the "Up" button below to take you to the Index page for this History section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment