Thought Constraints

Women Failing to Push Job ProspectsSometimes I think you have to march right in and demand your rights, - Somewhere on the Web

by Michael Bachelard Women sell themselves short in the workplace, lack negotiating skills and fail to put their hands up for new jobs and big pay rises, thus keeping their average pay below that earned by more aggressive men, the Australian Institute of Management has found. Public and private sector managers surveyed by the institute agreed men were more likely to promote themselves and seek out senior mentors to shepherd them up the ranks, and less likely to believe experience was a prerequisite for a high-paid job. As a result, men earn salaries commensurate with their potential, while women are paid according to what they have actually achieved. Institute of Management NSW chief executive Graeme Burns said the persistent problem of the pay gap between men and women was exacerbated by a workplace culture that considered leaving work to have a family as losing valuable career time. The institute held a series of focus groups with public and private sector managers after its salary survey showed the pay gap between men and women was up to 42% in some middle-management sectors, and the gap had not narrowed in 10 years. Mr Burns said corporate practice and culture were to blame, as well as entrenched attitudes. "Women are constrained by their own thinking and domestic circumstances," he said. Managers surveyed agreed the issue was a big problem for corporate Australia. "Unless women are placed in a position where they are supported and have the ability to stand up for more senior positions, then we are missing out on a huge bank of talent," Mr Burns said. One female manager said that when she asked a room full of men who among them wanted her job, almost all put their hands up. The same question to a group of women drew only a few volunteers. When it came to negotiating promotions, women were unwilling to ask for high salaries. Instead of negotiating arrangements that fulfilled their needs, they were more likely to trade off career development and higher pay in return for reduced hours and greater flexibility. Culturally, businesses should recognise that career paths were no longer linear, and taking time off for children was not career death but was little different from spending time in another job, Mr Burns said. The groups said the problem was as bad in the public sector as the private sector, despite more flexibility in the public service. One public sector manager saw little prospect of change in his department. "We won't see a female in the top three jobs in my lifetime," he said. But Recruitment Solutions managing director John Stewart said technology could change things more quickly than that by allowing more flexibility about where and how work was done. Organisations needed to change their culture by adopting more flexible work practices for both men and women, taking the emphasis off a solely linear career path, Mr Burns said. Source: The Australian Wednesday 11 April 2001

New Zealand Is One of the BEST and It's Still This Bad!Got Skills, Got Degree, but Not Salaryby Jan Corbett In the 20 years that 38-year-old Linda had been working for the same corporation she has watched as younger men have been promoted ahead of her. This year she thought her time had come. Although she now has a senior manager's role, Linda (not her real name) applied for further promotion to head office. She was told they were looking for someone with leadership skills and, because she had led teams of people before, she knew she had no problems there. With no family commitments, she also knew there were no issues about moving to a new city. Assessing the field of applicants, she thought her only real competitor for the job was a slightly older woman. So you can imagine the quiet fury with which she questioned her superiors when she found the job had gone to a younger man with technical, not leadership, experience. Of course they did not like being challenged over their decision, which is why so few women take that step. In her reflective moments she could see it made better business sense to appoint someone who didn't have to be relocated to fill the job and who would have been made redundant otherwise. He was the less-expensive option. And she is still prepared to believe there are opportunities with this company, which is why she has asked to remain anonymous. She has decided to be even smarter in how she plays the game. To be sure she doesn't miss out next time, she is studying for her MBA with, she says, a number of other women who like her have hit the glass ceiling and are ensuring they have all their armour in place next time they get the chance to smash through it. But she admits her commitment and loyalty to the company have waned. When lawyer Frances Joychild was working for the Human Rights Commission, she remembers how her telephone would ring about once a fortnight with an inquiry from a woman executive in a large company who had discovered a male colleague of the same or even more junior rank was either being paid more or being offered training or promotion opportunities not extended to her. These women "were hurt, depressed and demoralised", says Joychild. But they seldom laid formal complaints for fear of the long-term repercussions, the least of which would be having to resign. Linda says she would never lay a complaint because "it's a small network and you need these people to give you a reference". Stories like this go at least some way to explaining why, a full 30 years after it became illegal to pay a woman less than a man for doing the same job, women still earn less than men. Certainly this situation is not unique to this country. In Britain, for instance, women on average earn 82% of what men do. But the Census statistics showing women's median income for the year to March 2001 was $14,500 and men's was $24,900 do little to explain what is going on for individual women in the income stakes. That's because some of that gender pay gap can be explained by the average being dragged down by women who choose to work part-time, or not at all, or take less demanding roles for family reasons. When Statistics New Zealand did further research into the gender pay gap it found hours worked was a significant factor, although there is no accompanying research equating the number of hours spent at the office with productivity or effectiveness. The more telling gap is the disparity in the hourly income rate - women's is 84% of men's - but that, too, can be attributed to women taking jobs that pay less than men's. And jobs that women have traditionally done are invariably undervalued relative to men's traditional jobs. For instance, nurses and primary school teachers not only pay for their own training but are paid far less than police, who are paid to train. A first-year nurse begins on around $24,000, a teacher $29,000 and a new constable $46,000. The most astounding statistics instead come from university graduate surveys showing, for instance, that male commerce graduates start out in their careers earning on average nearly $5000 more a year than women of the same age with the same qualifications. And we're talking about women in their early 20s who are unlikely to have family demands piling on them just yet. Trudi McNaughton, executive director of the Equal Employment Opportunities Trust, refers to these results as clear evidence that the gender pay gap is not just about women taking time out to have children. She admits some of it might be explained by the type of jobs women graduates take. But just as often "it's to do with gender stereotyping in pay negotiations". From her discussions with male employers McNaughton has learned that when male job applicants demand more money they are viewed as just the sort of ambitious person the organisation needs. "But if women negotiate hard, a number of male managers have told me they find that intimidating. "If women get a negative response when they're assertive about salary it's not surprising they don't go for the top dollar in employment." Consider the surveys comparing men and women of similar age in similar senior positions. Executive recruitment company Sheffield released one in July showing executive women were earning 80% of the amount their male counterparts took home. And the older the women are, the greater the gap, suggesting ageism as well as sexism, according to Sheffield principal Simon Hart. Young women who therefore think equality is almost theirs have yet to see what happens to them as they age. While younger women in the survey of 1,200 are earning 96% of what the men earn, women aged over 55 are earning only 65% of the men's salaries. Yet 43% of the women executives have postgraduate qualifications, compared with only 27% of the men. While Hart says his consultants have not seen gender pay discrimination at the time an executive is appointed, "clearly something happens down the track". Hart thinks it may be that women are spending fewer hours in the office, but are working at home after the children are in bed, unseen by their superiors. Or it may be that they are not pushy about pay like the men. But as Trudi McNaughton has already pointed out, that's a losing strategy for women too. From her experience of interviewing eager young job-seekers, Maureen Eardley-Wilmot, past-president of Business and Professional Women and the co-owner of a city-based computer forensics firm, has seen that last factor in action. She describes how a young woman will apply for a job with the firm, say she is earning $28,000 but is prepared to drop to $25,000 to get the job. The male applicant will announce that he expects to be paid $35,000. If the firm wants to hire the young man, it will usually offer him $30,000. He will most likely accept, "but he'll let you know he expected $35,000 and that you're lucky to get him". The woman will be grateful to have been offered the job. "It's incredible that we're still seeing these gaps," says Hart, who sees the need for more research to discover exactly what is going on. The explanation could be that women executives simply do not perform as well as the men, but he doubts it. It could also be that women simply do not know what men are being paid. Frances Joychild believes the Privacy Act and the decline of collective bargaining have counted against women. The only way they find out what others are being paid is by chance. Joychild cites a case she was involved in 4 years ago where a senior woman executive discovered from a fax that a man more junior to her was being paid $15,000 more. The employer's argument was they had to pay a premium to get a man to work in the particular area. But she says official complaints like these are rare, because women have too much to lose by getting on the wrong side of their employer. Those who seek redress through the commission tend to be the young and unskilled with no other option and nothing to lose. Simon Hart says the only executive group where there is pay parity is human resource managers - a female-dominated niche. He thinks weight of numbers has levelled the field. Or it could be that they know most about salary scales. Career coaches say pay and conditions are two topics that women don't gossip about enough. Trudi McNaughton agrees, and says it can be worse where women are in the minority at work and not part of the office social networks like the regular crowd who drink after work or play rugby together. Such informal information networks can be more available to men than women. Not only does the rise of individual employment contracts and the demise of collective awards make it more difficult for women to assess their market value, but, according to Food and Service Workers Union general secretary Darien Fenton, the shift to a casualised workforce has made workers at the bottom of the heap more vulnerable to exploitation - and they tend to be women and more likely Maori and Pacific Island women. Not only is there a gender pay gap, but an ethnic one as well, meaning these women suffer a double whammy. In some cultures, says McNaughton, it is not acceptable to seek reward on your own behalf. Fenton says her own rise through the union movement to CTU vice-president has been a struggle achieved through "sheer bloodymindedness and the support of other women". She says she battles with that old bogey that "you're not womanly if you're tough". And because unions were forced to retrench during the last decade, many of the middle-management jobs held by women went, leaving "a log jam of men at the top". Apart from the basic injustice of women in comparable jobs earning less than men, it will ultimately lead to a burden on all taxpayers, according to the newly formed Women In Super organisation. It wants not only to encourage women to save for their retirement, but to change the way superannuation schemes are structured to reflect the fact that women with children have breaks in their earning years, or lose the benefits of their spouse's policy if the relationship ends. These issues for women clearly transcend class boundaries. So what are women supposed to do when being submissive doesn't get them anywhere and being assertive gets them even less? One piece of advice is to find out as much about the market rates and phrase your demands as being in line with those, rather than as a statement about your personal worth. Talk to a recruitment agency and get them to do some of that work. Trudi McNaughton's advice is to seek out jobs with companies that are EEO members and make it clear that's why you want to work for them. Fact file

Contact Jan Corbett at jan_corbett@nzherald.co.nz Source: nzherald.co.nz 2 September 2002 See also:

Revengeby Sue Dow, Palmerston North She'd charmed me all morning. Blonde, manicured, all smiles. "You remember me, then?" "To be honest - no." "Rosedale College. 1978. You dumped me. Wanted to spread your wings. Life experience you called it." My face fell. "Lynne Dobson?" "About your application. We're wanting more technical scope. And more life experience." Source: Book of Incredibly Short Stories by Brian Edwards Tandem Press 1997

Source: dumbentia.com

Expressing Anger Garners Power, Position and StatusWRATH, n. Anger of a superior quality and degree, appropriate to exalted characters and momentous occasions; as, "the wrath of God," "the day of wrath," etc... - Ambrose Bierce by Alan Mozes New York - Ambitious for a big promotion, a substantial raise, or merely some more raw power over others? If so, anger may indeed be your friend. New research suggests that controlled displays of outrage, defiance, and indignation is perceived as a sign of elevated position and status. "We definitely know that when people express anger they appear more dominant and strong, and when people saw someone express anger they thought that person was a lot smarter then someone who expressed a different emotion - namely sadness - and would confer on them a higher status,'' said study author Dr Larissa Z Tiedens. Tiedens conducted her research as a professor in the Graduate School of Business at Stanford University in California. Tiedens found that, overall, the study participants were more likely to support, vote for, learn from, promote, hire, give higher wages to, and view as competent any of the individuals who expressed their feelings in terms of anger rather than sadness. The study findings are published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Tiedens examined Stanford students' willingness to support and confer status to a person expressing sadness or anger. In one experiment, subjects watched two videos of former president Bill Clinton and two of an unknown political candidate. In a second set of experiments, employees at a software company rated their coworkers in terms of emotions, and the status they held in the company. And in the final experiment, students in a business class participated in role playing, and then rated the person after the encounter. She noted that displays of sadness were perceived as a sign of weakness - although such individuals were considered to be more warm and likeable. Displays of anger were seen as a sign of strength. Those people were thought to have a sense of "rightness" and the ability to get things done. Tiedens concluded that while being likeable is a desirable social trait it does not seem - at least in the short-run - to figure into estimations of how worthy an individual is of higher status and greater power. In an interview with Reuters Health, Tiedens suggested that the connection made between anger and status is relatively straightforward and easy to understand. "In my view, it's a pretty simple sort of mechanism where we use other people's anger expression as a signal of who they are and what their personality is like and what their capabilities are,'' she noted. "When we express anger what we're communicating is that 'I'm right and someone else is wrong'... and we want to confer status on those people who are right." However, Tiedens cautioned that tantrum-like expressions of anger may not have the same positive effect - perhaps leading to the perception that the individual is out of control. Short term gains that result from displays of anger may not help one hold on to the brass ring over time - even if it helps one to get it in the first place, according to anger expert, Dr Brad Bushman, a social psychology professor at Iowa State University. "I think that anger and aggression works in the short run, in that people who express their anger usually get what they want immediately,'' he told Reuters Health. "The problem is the long-term effect of this expression. It damages relationships with other people so although the person does gain status at the time it's not a very effective strategy in the long-run. But there's no doubt that people who express their anger usually get what they want." Source: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2001;80:86-94 as reported in Reuters Health Tuesday 23 January 2001

Anger Plays Key Role in Human Cooperationby Anil Ananthaswamy It¹s not love, affection or even blatant self-interest that binds human societies together - it's anger, according to Swiss researchers. They made the unsettling discovery while trying to fathom what makes people cooperate. Traditional explanations, such as kinship and reciprocal altruism, rely on genetic relationships or self-interest. These work for animals, but fail for humans because people cooperate with strangers they may never meet again, and when the pay-off is not obvious. Such cooperation can be explained if punishment of freeloaders or "free-riders" - those who do not contribute to a group but benefit from it - is taken into account. However, in real life, punishment is rarely without cost to the punisher. So why should someone punish a free-rider? Because of emotionally driven altruism, says Ernst Fehr, an economist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. All for OneTo test this "altruistic punishment" hypothesis, Fehr and his colleagues played an experimental game with six groups of four students each, in which real money was at stake. Each member was given 20 monetary units (MUs) to keep or invest in a group project. For every MU invested, the return for the group was 1.6 MUs, which was divided equally among the four members. So if only one person chose to invest, putting in 1 MU, she got back only 0.4 MU. But if everyone invested the full 20 MUs, they each ended up with 32 MUs, making total cooperation worthwhile. Investment, therefore, was always in the interests of the group, but never in the interest of the individual doing the investing. A free-rider would benefit from not investing. She could just gain from the money invested by others. After a series of six games, in which members' investments were anonymous and everyone invested simultaneously, Fehr found that members contributed an average of 10 MUs in the first game. But cooperation quickly unravelled, says Fehr. Contributions dropped to 4 MUs by the sixth game. Negative EmotionsSo Fehr decided to allow members to punish free-riders in their group, but at a cost. If a member punished another, it cost the punisher 1 MU and the punished 3 MUs. In six such games the average investment was always higher than in those without punishment, increasing to over 16 MUs. The threat of punishment sustained cooperation. Crucially, the punishment was an altruistic act, as the punisher would never encounter the same free-rider again. To understand the motive behind altruistic punishment, the researchers questioned the students about their emotions. They found that anger appeared to be the cause. "At the end of the experiment, people told us that they were very angry about the free-riders," says Fehr. "Our hypothesis is that negative emotions are the driving force behind the punishment." "It's a great experiment," says Herb Gintis, an expert on human cooperative behaviour at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. Social policies which do not provide an outlet for such emotions will fail, he says. In the 1980s, for instance, people revolted against the welfare state in the US because they felt that perceived freeloaders were not being taken to task. Journal reference: Nature volume 415 page 137 09 January 2002 Source: newscientist.com 9 January 2002 See also:

"Office Rage" Hits New LevelsMore than half of all office staff in the UK have become so angry at work they have nearly punched a colleague, according the results of a survey. Some 53% of workers have been brought to the brink of violence by "office rage", with loud-mouthed colleagues cited as the main cause. Malfunctioning computers, excessive workloads and interruptions during telephone conversations were also found to make employees' blood boil. The research, carried out by recruitment agency Pertemps, found that women were the most likely to nearly resort to violence while their male colleagues were more inclined to shout. Pertemps chairman Tim Watts said: "The latest annual British Crime Survey reveals 1.3 million incidents of violence at work, involving 604,000 workers. There are several pieces of legislation relating to violence in the workplace, including the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. It is important that employers are aware of their responsibilities in this area." Regular consultation between employers and employees to identify potential areas of conflict was vital to prevent workers being pushed over the edge, he added. The study, based on research among 450 office workers across Britain, found that 64% of those surveyed get angry at colleagues shouting across the office and talking over people at meetings. IT problems caused 53% to lose their temper, followed by excessive workloads (51%) and interruptions while on the phone (37%). Some 60% lost their temper regularly at work but although men shouted more than women (67% compared with 46%), women had the strongest desire to hit people who had upset them (51% compared with 39%). Asked how they coped with anger, nearly a third of respondents (31%) said they ignored the person responsible; 23%, the majority of whom were women, made a cup of tea, while 15% cursed under their breath. Eight per cent admitted to hitting their malfunctioning computer. The survey found that productivity is affected when staff are in a bad mood with 74% saying they did not work as well while angry. Fifteen per cent said they worked slower when their boss was angry for fear of making a mistake. Anger was said to have a detrimental effect on morale by 81% of respondents while 47% said longer hours, more responsibility and tighter deadlines had led to more cases of office rage in the last couple of years. Source: thisislondon.com This Is London 13 August 2002 © Associated Newspapers Limited

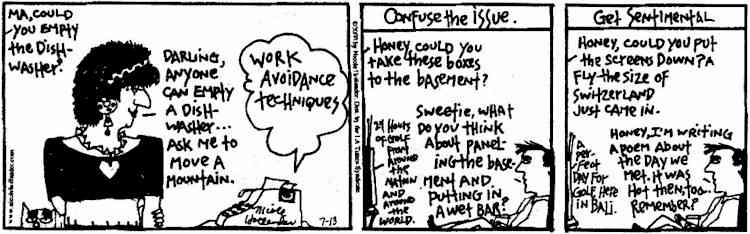

Work Avoidance

Source: Funny Times August 2000

For articles related to working including why, which career, bosses, time constraints, focus, trends, gender issues, pay differentials, getting laid off, getting re-hired, dependents, part-time work and

balancing work and values click the "Up" button below to take you to the Index page for this section on Working. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment