Neurologically Atypical

Carnegie Mellon and University of Pittsburgh Scientists Discover Biological Basis for AutismIf the human brain were so simple that we could understand it, we would be so simple that we couldn't. - Emerson M Pugh Pittsburgh - A team of brain scientists at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh have made a groundbreaking discovery into the biological basis for autism, a mysterious brain disorder that impairs verbal and non-verbal communications and social interactions. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, the researchers have found numerous abnormalities in the activity of brains of people with normal IQs who have autism. The new findings indicate a deficiency in the coordination among brain areas. The results converge with previous findings of white matter abnormalities in autism. (White matter consists of the "cables" that connect the various parts of the brain to each other). The new findings led the researchers to propose a new theory of the basis of autism, called underconnectivity theory, which holds that autism is a system-wide brain disorder that limits the coordination and integration among brain areas. This theory helps explain a paradox of autism: Some people with autism have normal or even superior skills in some areas, while many other types of thinking are disordered. In explaining the theory, Marcel Just, one of the study's lead authors and director of Carnegie Mellon's Center for Cognitive Brain Imaging, compared the brain of a normal person to a sports team in which the members cooperate and coordinate their efforts. In an autistic person, though some "players" may be highly skilled, they do not work effectively as a team, thus impairing an autistic's ability to complete broad intellectual tasks. Because this type of coordination is critical to complex thinking and social interaction, a wide range of behaviours are affected in autism. The research team believes these are the first findings in autism of differences in the brain activation patterns in a cognitive (non-social) task. The study produced two important new findings that help make sense of previous mysteries: The autistic participants had an opposite distribution of activation (compared to the control group) in the brain's two main language areas, known as Broca's and Wernicke's areas. There was also less synchronisation of activation among key brain areas in the autistic participants compared to the control group. To obtain technically acceptable fMRI data from high-functioning autistic participants, the researchers flew in people with autism from all over the eastern United States. High-functioning participants with autism (with IQ scores in the normal range) are rare, accounting for about 10% of all people with autism. Using non-invasive fMRIs, the team looked at the brains of 17 people with autism and 17 control subjects as they read and indicated their comprehension of English sentences. In both the healthy brains and in the brains with autism, language functions were carried out by a similar network of brain areas, but in the autism brains the network was less synchronised, and an integrating centre in the network, Broca's area, was much less active. However, another centre, Wernicke's area, which does the processing of individual words, was more active in the autism brains. The brain likely adapts to the diminished inter-area communication in autism by developing more independent, free-standing abilities in each brain centre. That is, abnormalities in the brain's white matter communication cables could lead to adaptations in the grey matter computing centres. This sometimes translates into enhanced free-standing abilities or superior ability in a localized skill. These findings provide a new way for scientists and medical researchers to think about the neurological basis of autism, treating it as a distributed system-wide disorder rather than trying to find a localized region or particular place in the brain where autism lives. The theory suggests new research to determine the causes of the underconnectivity and ways to treat it. If underconnectivity is the problem, then a cognitive behavioural therapy might be developed to stimulate the development of connections in these higher order systems, focusing on the emergence of conceptual connections, interpretive language and so on. Eventually, pharmacological or genetic interventions will be developed to stimulate the growth of this circuitry once the developmental neurobiology and genetics of these brain connections are clearly defined by research studies such as these. The research team is jointly headed by Just, the D O Hebb Professor of Psychology at Carnegie Mellon, and Dr. Nancy Minshew, professor of psychiatry and neurology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and director of its Center for Autism Research. Individuals with High Functioning Autism and Asperger's Syndrome between 10 and 55 years of age who are interested in participating in similar studies can send email to autismrecruiter@upmc.edu or call Nikole Jones at 412-246-5481. Source: websitetoolbox.com 27 July 2004

Scientists Say Most Can Read Mindsby Ker Than Empathy allows us to feel the emotions of others, to identify and understand their feelings and motives and see things from their perspective. How we generate empathy remains a subject of intense debate in cognitive science. Some scientists now believe they may have finally discovered its root. Most of us are essentially mind readers, they say. The idea has been slow to gain acceptance, but evidence is mounting. Mirror NeuronsIn 1996, three neuroscientists were probing the brain of a macaque monkey when they stumbled across a curious cluster of cells in the premotor cortex, an area of the brain responsible for planning movements. The cluster of cells fired not only when the monkey performed an action, but likewise when the monkey saw the same action performed by someone else. The cells responded the same way whether the monkey reached out to grasp a peanut, or merely watched in envy as another monkey or a human did. Because the cells reflected the actions that the monkey observed in others, the neuroscientists named them "mirror neurons." Later experiments confirmed the existence of mirror neurons in humans and revealed another surprise. In addition to mirroring actions, the cells reflected sensations and emotions. "Mirror neurons suggest that we pretend to be in another person's mental shoes," says Marco Iacoboni, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine. "In fact, with mirror neurons we do not have to pretend, we practically are in another person's mind." Since their discovery, mirror neurons have been implicated in a broad range of phenomena, including certain mental disorders. Mirror neurons may help cognitive scientists explain how children develop a theory of mind (ToM), which is a child's understanding that others have minds similar to their own. Doing so may help shed light on autism, in which this type of understanding is often missing. Over the years, cognitive scientists have come up with a number of theories to explain how ToM develops. The "theory theory" and "simulation theory" are currently two of the most popular. Theory theory describes children as budding social scientists. The idea is that children collect evidence - in the form of gestures and expressions - and use their everyday understanding of people to develop theories that explain and predict the mental state of people they come in contact with. Vittorio Gallese, a neuroscientist at the University of Parma in Italy and one of original discovers of mirror neurons, has another name for this theory: he calls it the "Vulcan Approach," in honour of the Star Trek protagonist Spock, who belonged to an alien race called the Vulcans who suppressed their emotions in favour of logic. Spock was often unable to understand the emotions that underlie human behaviour. Gallese himself prefers simulation theory over this Vulcan approach. Natural Mind ReadersSimulation theory states that we are natural mind readers. We place ourselves in another person's "mental shoes," and use our own mind as a model for theirs. Gallese contends that when we interact with someone, we do more than just observe the other person's behaviour. He believes we create internal representations of their actions, sensations and emotions within ourselves, as if we are the ones that are moving, sensing and feeling. Many scientists believe that mirror neurons embody the predictions of simulation theory. "We share with others not only the way they normally act or subjectively experience emotions and sensations, but also the neural circuits enabling those same actions, emotions and sensations: the mirror neuron systems," Gallese said. Gallese points out, however, that the two theories are not mutually exclusive. If the mirror neuron system is defective or damaged, and our ability to empathise is lost, the observe-and-guess method of theory theory may be the only option left. Some scientists suspect this is what happens in autistic people, whose mental disorder prevents them from understanding the intentions and motives of others. Tests UnderwayThe idea is that the mirror neuron systems of autistic individuals are somehow impaired or deficient, and that the resulting "mind-blindness" prevents them from simulating the experiences of others. For autistic individuals, experience is more observed than lived, and the emotional undercurrents that govern so much of our human behaviour are inaccessible. They guess the mental states of others through explicit theorising, but the end result is a list - mechanical and impersonal - of actions, gestures and expressions void of motive, intent, or emotion. Several labs are now testing the hypothesis that autistic individuals have a mirror neuron deficit and cannot simulate the mental states of others. One recent experiment by Hugo Theoret and colleagues at the University of Montreal showed that mirror neurons normally active during the observation of hand movements in non-autistic individuals are silent in those who have autism. "You either simulate with mirror neurons, or the mental states of others are completely precluded to you," said Iacoboni. Source: news.yahoo.com Wednesday 27 April 2005 from LiveScience.com

Assault on Autism:

|

| Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Institute of Medicine. 2004. Immunization Safety Review: Vaccines and Autism. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Available at www.nap.edu. | |

| Hornig, M, D Chian, and W I Lipkin. 2004. Neurotoxic effects of postnatal thimerosal are mouse strain-dependent. Molecular Psychiatry 9 (September) : 833 - 845. Abstract available at dx.doi.org. | |

| Shi, L, N Tu, and P H Patterson. In press. Maternal influenza infection is likely to alter fœtal brain development indirectly: The virus is not detected in the fœtus. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. Abstract available at dx.doi.org. | |

| Shi, L . . . and P H Patterson. 2003. Maternal influenza infection causes marked behavioural and pharmacological abnormalities in the offspring. Journal of Neuroscience 23 (Jan. 1) : 297 - 302. Available at www.jneurosci.org. | |

| Waly, M . . . and R C Deth. 2004. Activation of methionine synthase by insulin-like growth factor-1 and dopamine: a target for neurodevelopmental toxins and thimerosal. Molecular Psychiatry 9 (April) : 358 - 370. Abstract available at dx.doi.org. |

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Vaccine Program) has an autism prevalence fact sheet available at www.hhs.gov.

Further Readings:

Bower, B 2004. Brain development disturbed in autism. Science News 166 (July 31) : 78. Available to subscribers at www.sciencenews.org.

______. 2002. Autism leaves kids lost in face. Science News 161 (June 29) : 408. Available to subscribers at www.sciencenews.org.

Christensen, D 2001. Vaccine verity. Science News 160 (August 18) : 110 - 111. Available at www.sciencenews.org.

Harder, B 2002. Study exonerates childhood vaccine. Science News 162 (November 30) : 349. Available to subscribers at www.sciencenews.org.

Travis, J 2003. Autism advance: Mutated genes disrupt nerve cell proteins. Science News 163 (April 5) : 212. Available to subscribers at

www.sciencenews.org.

Sources:

|

Lisa A Croen Division of Research Kaiser Permanente – California 2000 Broadway Oakland, California 94612 |

Beth Crowell 208 South Street Box 801 Housatonic, Massachusetts 01236 |

Michael Cuccaro Duke University Center for Human Genetics DUMC Box 2903 Durham, North Carolina 27710 |

|

Richard Deth Northeastern University 312 Mugar Hall 360 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 |

Mady Hornig Mailman School of Public Health Columbia University 722 W 168th Street, Room 1801 New York, New York 10032 |

National Alliance for Autism Research 99 Wall Street Research Park Princeton, New Jersey 08540 Website: www.naar.org |

|

Craig Newschaffer Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions 615 N Wolfe Street, E6040 Baltimore, Maryland 21205 |

Paul H Patterson Division of Biology, 216-76 California Institute of Technology Pasadena California 91125 |

Isaac Pessah 4117 Meyer Hall University of California, Davis One Shields Avenue Davis, California 95616 |

|

Andy Shih National Alliance for Autism Research 99 Wall Street Research Park Princeton, New Jersey 08540 |

Thomas Wassink University of Iowa Department of Genetics 1178 Medical Laboratories Iowa City, Iowa 52242 |

Andrew Zimmerman Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Kennedy Krieger Institute 707 North Broadway Baltimore, Maryland 21205 |

Source: sciencenews.org Science News 13 November 2004 Vol 166 No 20 p 311 © Science Service all rights reserved

To subscribe to Science News (print), go to kable.com. To sign up for the free weekly e-LETTER from Science News, go to www.sciencenews.org.

![]()

Immune System, Blood Altered in Autism

Children with autism show different immune system responses from children without the condition, and these might be measured in the blood for a possible screening test, US researchers reported. Two studies presented to a conference on autism help support other research that suggests subtle differences in the immune function of children with autism. Autism is a brain disorder usually seen as children become toddlers. Affecting an estimated 2 to 5 out of every 1,000 children, autism has a spectrum of symptoms that include difficulty with social interaction and repetitive behaviours. No one knows what causes autism, although experts have largely rejected purported links with childhood vaccines.

Scientists at the 4th International Meeting for Autism Research in Boston presented studies looking at the blood of children with autism. Judy Van de Water of the University of California, Davis, and colleagues separated immune cells from 30 children with autism and 26 non-autistic children aged 2 to 5. They mixed in toxins and bacteria. In response to bacteria, the researchers saw lower levels of immune signalling proteins called cytokines in the group with autism. These children also had irregular responses to a plant protein, but not to other toxins or to a measles, mumps and rubella vaccine. "Understanding the biology of autism is crucial to developing better ways to diagnose and treat it," Van de Water said in a statement.

A second team at the same centre took blood samples from 70 children aged 4 to 6 with autism and from 35 other children. The children with autism had 20% more immune system cells called B cells and 40% more natural killer cells. There also seemed to be differences in other proteins in the blood, although the researchers are still sifting through the data. "From these results we think it is highly likely that there are differences we can detect in blood samples that will be predictive of the disorder, though we are still some years away from having an actual diagnostic blood test for autism," said researcher David Amaral, who led the study.

What good would this do, as there is no cure? "There is a growing view among experts that not all children with autism are 'doomed to autism' at birth," Amaral said in a statement. "It may be that some children have a vulnerability, such as a genetic abnormality, and that something they encounter after being born, perhaps in their environment, triggers the disorder," he added. "Studying the biological signs of autism could lead to new ways to prevent the disorder from ever occurring. And even if it can't be prevented, intervening early in life - ideally shortly after birth - could greatly improve the lifetime outlook for children with autism."

Source: news.yahoo.com Thursday 5 May 2005

![]()

On the Other Hand...

Source: "Autism: Out of the Deep freeze" The Economist print edition 9 January 2003

![]()

What Is Autism?

Research suggests levels of autism have increased 10-fold over the last decade. Autism is a developmental aberration that affects the way a person communicates and interacts with other people. People with autism cannot relate to others in a meaningful way. They also have trouble making sense of the world at large. As a result, their ability to develop friendships is impaired. They also have a limited capacity to understand other people's feelings.

Autism is often also associated with learning disabilities. Reality to an autistic person can be a confusing, interacting mass of events, people, places, sounds and sights. There sometimes seems to be no clear boundaries, order or meaning to anything. A large part of life is spent just trying to work out the pattern behind everything.

Triad of Autistic Impairments

Manifestations vary with the severity of the disability. Changes occur with age, especially in those with higher levels of ability; different aspects of the behaviour pattern are more obvious at some ages than at others.

Education and the social environment can have marked effects on overt behaviour; in a very structured setting, with one to one attention, the autistic behaviour may not be shown in any obvious way. It should also be remembered that all children have their own personality, which affects their reaction to their disabilities.

| Impairment of social interaction - The most severe form is aloofness and indifference to other people although most enjoy certain

forms of active physical contact and show attachment on a simple level to parents or carers. In less severe forms, the individual passively accepts social contact, even showing some pleasure in this, though he or she does not make spontaneous approaches. Some children or adults with the triad approach other people spontaneously, but do so in an odd, inappropriate, repetitive way and pay little or no attention to the responses of the people they approach. Among the most able adolescents and adults, the social impairment may have evolved into an inappropriately stilted and formal manner of interaction with family and friends as well as strangers. It has been suggested that the problem underlying social impairment is lack of the in-built ability to recognise that other people have thoughts and feelings - the absence or impairment of a so-called "theory of mind". | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Impairment of social communication - A lack of appreciation of the social uses and the pleasure of communication is always present

in one form or another. This is true even of those who have a lot of speech, which they use to talk "at" others and not with them. A lack of understanding that

language is a tool for conveying information to others is another typical example of the communication impairment. Some are able to ask for their own needs but have

difficulty in talking about feelings or thoughts and in understanding the emotions, ideas and beliefs of other people. Many are unable to convey or comprehend information by using gesture, miming, facial expression, bodily posture, vocal intonation et cetera. Some more able people do use gestures but these tend to be odd and inappropriate. Those with good vocabularies have a pedantic, concrete understanding and use of words, an idiosyncratic, sometimes pompous choice of words and phrases, and limited content of speech. Some verbal autistic people are fascinated with words and word games but do not use their vocabularies as tools of social interaction and reciprocal communication. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Impairment of imagination - In children, inability to play imaginatively with objects or toys or with other children or adults is

an outward manifestation of this impairment. A tendency to select for attention minor or trivial aspects of things in the environment instead of an imaginative understanding

of the meaning of the whole scene is often found (for example attending to one earring instead of the whole person, a wheel instead of the whole toy train). Some of these children display a limited range of imaginative activities, which may be copied, for example, from tv programmes, but they pursue these repetitively and cannot be influenced by suggestions from other children. Such play may seem very complex, but careful observation shows its rigidity and stereotyped nature. Some read particular types of books, such as science fiction, but the interest is limited and repetitive. Some confuse fiction and reality and tell rambling stories they seem to believe are true. Some do not know the difference between dreams and reality. Many lack understanding of the purpose of any pursuits that involve comprehension of words and their complex associations, for example, social conversation, literature, especially fiction, subtle verbal humour (though simple jokes may be enjoyed). There is a consequent lack of motivation to indulge in these activities, even if the necessary skills are available. In adults, the proper development of imagination is shown in the ability to use past and present experiences (both one’s own and other people’s, the latter from personal social communication and books, plays and films) in order to predict consequences of actions and make plans for the short and long term future. This aspect of the mature imagination is conspicuously lacking in people with autistic spectrum disorders, whatever their level of ability. The consequence of the impairment of imagination is a very narrow range of repetitive activities or special interest. These can take simple or complex forms. Children of higher levels of ability tend to show more complex routines. The following are only some examples of stereotyped activities. The possible variations on this theme are endless. Simple stereotyped activities include:

Complex stereotyped activities involving objects include:

Complex stereotyped activities involving routines include:

Complex verbal or abstract repetitive activities include:

|

Other Features That May Be Present

In addition to the essential diagnostic criteria listed, there are some other features that are common but not essential for diagnosis.

| Problems affecting formal language (in addition to the essential communication impairments mentioned above) including difficulties in comprehension and use of speech as in developmental language disorders | |

| Odd responses to sensory stimuli, such as hypersensitivity to sound, fascination with visual stimuli, dislike of gentle touch but enjoyment of firm pressure et cetera | |

| Poor motor co-ordination including clumsiness, odd gait and posture | |

| Over or under activity | |

| Abnormalities of mood, such as excitement, misery | |

| Abnormalities of eating, drinking, sleeping | |

| Physical disabilities, such as epilepsy, sensory impairments, Down’s syndrome or any other | |

| Additional developmental disorders affecting language, reading, writing, number work et cetera | |

| Psychiatric conditions, such as depressions, anxiety, catatonia, "psychotic states" | |

| Disturbance of behaviour such as aggression, self injury, running away, screaming et cetera | |

| Special skills. About 10% of children with autistic spectrum disorders have some special skill at a much higher level than the rest of their abilities - for example, music, art, numerical calculations or jigsaw puzzles. Some have a remarkable memory for dates and things that particularly interest them. For example, people with Asperger syndrome often develop an almost obsessive interest in a hobby or collection. Usually their interest involves arranging or memorising facts about a specialist subject, such as train timetables, Derby winners or the dimensions of cathedrals. |

Source: www.nas.org.uk The National Autistic Society's introduction to the autistic spectrum disorder

Internet link: National Autistic Society www.oneworld.org/autism_uk

![]()

Love Is a Many-Moleculed Thing

by Lewis Wolpert

The most characteristic feature of autism is the child's lack of a theory of other people's minds. The classic test for this involves putting a sweet in a red box in front of John and Mary and then sending Mary out of the room. The sweet is moved to the blue box and John is asked where Mary will look for it when she returns. If John is autistic he will say Mary will look in the blue box as he cannot understand what Mary would really think. Such children have severe social behaviour difficulties.

A different view from Hobson's is that because many suffering from autism have special skills in, for example, maths and music, their mode of thought is biased towards local rather than social thinking. The cause of autism remains unknown as does the reason why many more boys are autistic than girls.

Source: guardian.co.uk Sunday 24 March 2002 from an Observer review of The Cradle of Thought by Peter Hobson

![]()

Neurologically Atypical: Different Sensory Experiences/Different Worlds

by Olga Bogdashina

Since the first identification of autism in 1943 (Kanner) a lot of research has been carried out to study this condition from different perspectives. What has not been taken into account by the experts in the field, however, is the opinion of the "native experts" - autistic individuals themselves. Despite the fact that many people with autism have tried to communicate their views and insights, these attempts have mostly passed without much professional notice, one of the reasons being, their views and insights are unconventional to the majority of people (so-called "normal" people).

"Different" does not mean "abnormal" or "defective", and "normalcy" is a very relative term, as the "norm" is often applied to the performance of majority, and it is more justifiable to term it "typical". To avoid having to use the term "normal", autistic people at Autism Network International have introduce a new term - "Neurologically Typical" (NT) to describe non-autistic people.

No two autistic people appear to have the exactly same patterns of sensory-perceptual experiences. It is vital to understand the way autistic people experience the world, as often very well-meaning specialists are failing people with autism (and) most (autistic people) have not been helped at all, many have felt degraded and some have been harmed (Gerland, 1998) because of the misunderstanding and misinterpretation of the condition.

Understanding of the way autistic people experience the world will bring respect to people with autism in their attempts to survive and live a productive life in our world instead of unacceptance often exhibited by the general public.

Autistic people seem to perceive everything as it is. It is sort of "literal perception", for example, they may see things without interpretation and understanding (literal vision). There is much evidence that one of the problems many autistic people experience is their inability to distinguish between foreground and background stimuli (inability to filter foreground and background information). They are often unable to discriminate relevant and irrelevant stimuli. What is background to others may be equally foreground to them; they perceive everything without filtration or selection.

As Donna Williams (1996) describes it, they seem to have no sieve in their brain to select the information that is worth being attended. It can be described as "gestalt perception", that is, perception of the whole scene as a single entity with all the details perceived (not processed!) simultaneously. They may be aware of the information others miss, but the processing of "holistic situations" can be overwhelming. Their difficulty to filter background and foreground information caused by gestalt perception leads to rigidity of thinking and lack of generalisation. They can perform in the exactly same situation with the exactly same prompts - a familiar room may seem different and threatening if the furniture has been slightly rearranged, for example. Autistics need sameness and predictability to feel safe in their environment. If something is not the same, it changes the whole gestalt of the situation and they may not know what they are expected to do. It brings confusion and frustration. Paradoxically, autistic people have much more trouble with slight changes than with big ones. For example, they can cope with going somewhere unfamiliar much better than with changes in the arrangement of the furniture in their room.

On a perceptual level the inability to filter foreground and background information may bring sensory overload. Autistics are bombarded with sensory stimuli. They are "drowned" in them. For individuals with "auditory gestalt" perception, extreme effort must be made to understand what is being said if there is more than one conversation going on in the room or more than one person speaking at a time. They are bombarded with noises from all directions. If they try to screen out the background noise they also screen out the voice of the person they try to listen to.

Olga Bogdashina received her Phd in Linguistics from Moscow Linguistics University and her MA Ed Autism from Sheffield Hallam University. Olga’s son, aged 13, is autistic. She has worked extensively in the field of autism as teacher, lecturer and researcher, with a particular interest in sensory-perceptual and communication problems in autism.

Source: autismtoday.com

![]()

Murdering to Dissect

by Edward Skidelsky

Book Review

Hobson pursues what it is to be human by investigating a group of people who are in many ways distinctly unhuman - autistics. Autistics are not always retarded; they may be exceptionally intelligent. Their specific problem is understanding other human beings. It is only with great difficulty that they learn to recognise human beings as human beings, distinct from mere things. "I really didn't know there were people until I was seven years old," said a young autistic adult. "I then suddenly realised there were people. But not like you do. I still have to remind myself that there are people." Autistics, in other words, have to "work out" that there are other people. This is what Descartes and many other philosophers following him thought that we all do. But the very strangeness of autistics demonstrates that this is not how most of us relate to others. It illuminates, by contrast, how our knowledge of other minds is direct, not inferential. Hobson quotes Wittgenstein:

My attitude towards him is an attitude towards a soul. I am not of the opinion that he has a soul.

Autistics, you might say, are not of the opinion that other people have souls.

To demonstrate this, Hobson devised an experiment that could almost have been inspired by a remark of Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein noticed that it is very hard to detect the expression of a face drawn upside down, even if it is accurate in all its physical details. Expression, in other words, is not simply a summation of physical details; it is a total "Gestalt". Hobson asked two groups of children, one autistic and one non-autistic, to sort upside-down faces according to their expression. The autistic group performed much better. This is because, Hobson concludes, "the 'emotions' were no longer recognisable as emotions when the faces were presented upside down. Effectively, the task was reduced to one of pattern or feature recognition." The exercise having thus been rendered meaningless from an emotional point of view, the autistics had the upper hand.

Autistic children, he notes, do not engage in symbolic play like normal children. They will not spontaneously pick up a matchbox and pretend it is a car; they instead spend their time in meaningless, mechanical rituals, such as spinning a wheel. Hobson offers an interesting explanation for this. To use symbolism is to treat one thing as another thing. Our ability to do this is based on our capacity to step outside our minds, to see things from another person's point of view. From about the age of 12 months, normal infants can "shift perspectives" in this way. They can identify their mother's attitude and incorporate it into their own attitude. This is precisely what children with autism cannot do. Hobson argues that this basic human capacity for empathy prepares the ground for language and all other specialised forms of symbolism. "One can use symbols only if one has the kind of emotional life that connects one with the world and others." Emotion is, as the title of the book suggests, "the cradle of thought".

Source: newstatesman.co.uk Monday 25th March 2002

![]()

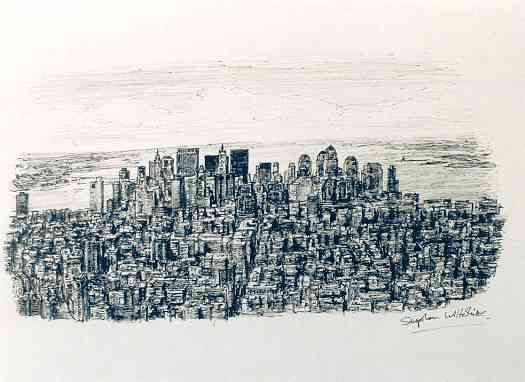

Triumph in Adversity

Stephen Wiltshire has been the subject of numerous documentaries and one man exhibitions

since his discovery in the 1980's when he was 9. He is an autistic savant who retains virtual

photographic memory recall of people and places, enabling him to draw, with near perfect accuracy,

representations of city skylines and architectural scenes. Some of his drawings measure

over 9ft in length, others are much smaller; all possess his astonishing virtuoso draughtsmanship skills.

by Hugh Freeman

Review of An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales

by Oliver Sacks

Knopf/Picador 1995

Puzzling neurophysiologically is autism, illustrated here by two unusually gifted people. The "savant" artist Stephen Wiltshire is already well known through his topographical drawings, but Sacks - who has spent much time with him - ends up largely baffled by what is missing in him as a person: "all our models ... break down before him." Autism affects nearly one in 7,000 people, half of these never use speech and 95% lead very restricted lives. Even the few gifted ones show "a radically different, almost alien mode of mind and being". Their gifts, though, seem to support Howard Gardner's advocacy of separate forms of intelligence, each with its own algorithms. The autistic are impaired in social interaction, communication and imagination, lacking a normal ability to perceive their own and others' state of mind. In the end, Sacks regrets that proper understanding may demand both technical and conceptual powers that are for now beyond our capabilities.

Source: Nature Vol 377 12 October 1995

![]()

Differences Found in Autistic Brains

Researchers have identified structural differences in the brain of people with autism that may explain why they have problems communicating and socialising. Scientists used computerised imaging techniques to pinpoint differences in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain.

Autism is a developmental disability that affects the way a person communicates and interacts with other people. People with autism cannot relate to others in a meaningful way. They also have trouble making sense of the world at large. As a result, their ability to develop friendships is impaired. They also have a limited capacity to understand other people's feelings.

The scientists examined brain tissue from 9 autistic patients and 9 people who did not have the condition. They focused on structures within the brain known as cell minicolumns which play an important role in the way the brain takes in information and responds to it. The cell minicolumns of autistic patients were found to be significantly smaller, but there were many more of them.

Researcher Dr Manuel Casanova said the increased amount of cell minicolumns in autistic people could mean that they are constantly in a state of overarousal. Their poor communication skills could be an attempt to diminish this arousal.

Brainstem Damage

Previous research has suggested that autism is linked to damage to a part of the brain called the brainstem in the early stages of development. It is thought that this early injury might somehow interfere with the proper development or wiring of other brain regions resulting in the behavioural symptoms of autism.

A spokesperson for the UK National Autistic Society said the new research was consistent with this theory. "If the ability for complex communication is due to the subtle wiring of the millions of minicolumns found throughout the brain then any early impairments in development could explain the difficulties faced by people with autism spectrum disorders in the world. Potentially it might lead to an understanding of how to help these individuals although this is a long way off. Certainly the study reported is consistent with what is known about the difficulties people with autism spectrum disorders face in processing information."

The frontal lobe of the brain is concerned with reasoning, planning, parts of speech and movement, emotions, and problem-solving. The temporal lobe is concerned with perception and recognition of sounds and memory.

The new research was carried out by scientists at the Medical College of Georgia, the University of South Carolina, and the Downtown VA Medical Center in Augusta, Georgia. It is reported in Neurology, the scientific journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

Source: healthlinkusa.com Tuesday 12 February 2002

![]()

Trust Begets Hormone: Oxytocin May Help Humans Bond

by Helen R Pilcher

Trust begets trust - and the hormone oxytocin, research reveals. The chemical messenger may help humans to bond, researchers told this week's Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana. People's oxytocin levels rise when they receive a signal of trust, says Paul Zak from Claremont Graduate University in California. Those with the highest hormone levels are more likely to be generous in return and so are more trusting, he says.

Zak's team gave 19 people $10 apiece. Each person was invited to share their reward with an anonymous recipient. The recipients' money was then tripled and they were allowed to send a share back to the donors. The researchers found that 54% of recipients returned money to donors. Those who gave and returned most generously had the highest oxytocin levels.

Women in the study who were ovulating were less likely to be trusting, the team also found. This makes sense, says Zak. Females who could get pregnant need to protect their resources. And they need to be selective in their interpretation of social signals so as to choose the best mate, he reasons.

The study may also shed light on the causes of autism, says neuroscientist Richard Frackowiak from University College London: autistic people often trust too much. Oxytocin sends signals to cells in the amygdala - a brain region involved in emotion and social behaviour and implicated in autism.

Oxytocin prompts new mothers to release breast milk, strengthening the bond between mother and child. Touching boosts oxytocin levels in rats. The chemical also suppresses stress hormones.

Source: nature.com November 2003 © Nature News Service

![]()

I can see where autists may be too trusting - perhaps they have little choice - but the bonding thing seems counterintuitive. Perhaps they bond with themselves?

![]()

Adults with Asperger's Syndrome Often Go Undiagnosed

by Irene Cullen

About one in 250 people has Asperger's Syndrome, a neurological disorder that affects one's ability to understand and respond to others' thoughts and feelings, according to clinical psychologist Tony Attwood. Yet, because research conducted by Hans Asperger in 1944 did not receive widespread attention until the 1990s, many adults with the disorder remain undiagnosed. Those with moderate to mild Asperger's are most likely to have partners and children, and also are most able to hide their symptoms. Often, they only feel comfortable within the intimate relationships of a family, so others cannot see the struggles they and their families face.

"I call myself a translator between two different worlds," said Attwood, who is coauthor of a book on adults with Asperger's titled, Making Friends and Managing Feelings, which is due out next year. "I explain the world of the neuro-typical to the Asperger person, and the world of the Asperger to the neuro-typical." These relationships resemble the blending of two cultures, Attwood said at an autumn workshop sponsored by Families of Adults Afflicted with Asperger's Syndrome in Centerville. Attwood's upcoming book, written with Carol Gray, who invented "social stories", a key tool in educating children with Asperger's, takes a positive attitude toward working out the problems of adults with Asperger's.

Asperger's affects each person uniquely, Attwood said. It is composed of an array of qualities, in varying degrees. At the workshop, Attwood mapped out the characteristics, problems, and recommend strategies. A profile of abilities common to Asperger's includes:

| Codes of social conduct: "They are mind-myopic," Attwood said. "They can't know what other people are thinking or feeling. They are not badly brought up, or trying to upset you. They are just unaware of the social script. It is as if they were from another culture, and unaware of our norms." | |

| Empathy: "When we look at empathy, it's very complicated. In a relationship with a partner, that is crucial - knowing when you need emotional support," Attwood said. Those with Asperger's may have trouble understanding a partner's feelings, and vise versa. | |

| Friendship skills: "They may find it hard to meet peers on an equal level, be uninterested in friendship, or rely on their spouse for advice on office politics and teamwork," he said. | |

| Characterisation of people: They "may see others in black and white, as either likable or not, or be poor judges of character and get taken advantage of. The spouse must take his or her care-taking role seriously," he said. | |

| Art of conversation: Neuro-typical people look for patterns when communicating verbally to find the general meaning, he said, but "Asperger's people create their own pattern or, if they cannot, remember the whole message and may miss what is important." |

Attwood noted that Asperger's may also be characterised by a strong desire for perfection, a special interest or talent, a fondness for routine, poor coordination, high cognitive skills, low organisational skills, and uneven processing of sensory input - being more or less sensitive than most. Because neuro-typical people can understand another person's point of view, he said, they can switch strategies or compromise to get along. With less social intuition and a reduced ability to pick up their body's internal physical signals associated with various feelings, people with Asperger's may have trouble managing their emotions. "They have fewer social-repair mechanisms in their toolbox, are predisposed to mood swings, and can eventually explode," Attwood said. "If they are not careful, anger is a major issue."

To learn social skills, people with Asperger's compensate for what they lack in intuition with their intellect, Attwood said. sometimes that works. "If the Asperger's person wants that relationship to work, they will learn to do what they need to do to make it work. If they don't, whatever you try to teach them, they will not put to use," Attwood said. Asperger people can use counselling effectively to help them learn about themselves, about how to compromise, to be open-minded, or to change their behaviour to be more like others, he said.

What draws a neuro-typical person and someone with Asperger's together? Some strengths associated with Asperger's include: strong ability in their career or special interest, attention to detail, conversation free of hidden meaning, advanced vocabulary or general knowledge, unique perspective in problem solving, exceptional memory, a sense of social justice, and practicality in issues of mortality and grief. Partners may admire their intellect or abilities, have compassion for their limited social skills, believe that their character is due to childhood circumstances, share their interests, appreciate their fidelity or standing in the community, see them as creative or as a parent figure, and enjoy the degree of adulation they provide. For women, an Asperger's man may seem like the strong, silent type, Attwood said.

People with Asperger's, on the other hand, may be attracted to someone with a similar profile of abilities, a maternal woman or caregiver, or someone with strong opposite qualities such as flexibility and compassion.

Men may get into a more traditional marriage in which they play a dominant role, an arranged marriage, or relationship with someone from another culture. As for many couples, children create complications. But as it does for many parents, this can be one relationship that motivates people with Asperger's to overcome their limitations to make it work. One vulnerability is a lack of understanding of the natural stages of childhood development, because their own experience was different. They may want to let their partner act as a go-between or a diplomat on certain issues involving the children.

People with Asperger's also may feel a rivalry with children, because sacrificing their own needs does not come naturally. They may need to make an effort to show affection and emotional support, learn to tolerate some degree of messiness and noise, and try not to be too critical, Attwood said.

In social situations with friends and family, two-way misinterpretations of signals can occur, Attwood said. When the partner tries to talk about the situation, he or she may experience what Attwood called the Cassandra Phenomenon. In Greek mythology, Cassandra was given the gift of prophecy, but fated to have no one believe her. "With Asperger's, life is a stage," Attwood said. "The curtain goes up while they are in public and down when they are at home. Because other people do not see the problem, they question your sanity - you are on your own. In some families, denial has held the family together for generations, and you want to bring down the scaffolding." As a result, the neuro-typical partner may actually need more support than the one with Asperger's. Therefore, contact with other partners through newsletters, a support group, or an Internet site is vital. "You cannot get this knowledge from professionals," Attwood said. He also recommended having an independent social life and an occasional vacation apart.

Strengthening these unions requires vigilance and work - on both sides. Useful strategies include: acceptance of the diagnosis as a difference not a defect, motivation to change, family support, relationship counselling, emotional-management strategies, guidance in social skills, and open and effective communication.

Resources:

Tony Attwood's website is: tonyattwood.com

Families of Adults Afflicted with Asperger's Syndrome website: faaas.org

Asperger's Association of New England (for all ages) website: aane.org

Source: Boston Globe 18 February 18 2001

![]()

Revenge of the Nerds

Once outcasts, some autistics now see the condition as a cognitive gift and even the next stage in human evolution - at the dawn of the transhuman age, who's to say they're wrong?

by George Dvorsky

It was hard to believe that that the words were coming from a 7-year-old boy. "Another characteristic of mammals is that they give placental births," he said, "oh, except marsupials like kangaroos and koala bears." Changing gears slightly he continued, "And then there are animals with endoskeletons and exoskeletons. Humans, because they have bones on the inside of their bodies have endoskeletons, but insects have exoskeletons on the outside." With a vocabulary more closely resembling that of someone in grade 9, he chimed off the bits of scientific triviata as if he were directly linked to Wikipedia.

Clearly, this was no ordinary 2nd grader, whom I chatted with recently at a Toronto specialist's office. Compared to other kids with Asperger's syndrome, however, his abilities are considered quite typical. His younger brother, who also has Asperger's, is already doing multiplication tables in his head while most of his kindergarten classmates are still trying to count to 10. The boy also has social interaction and behavioural problems typical of those with Asperger's. He tends to construe all advances from his classmates as bothersome, for example, compulsively chews on his sleeves and frequently stands up to spin in class. This is pretty textbook stuff for "Aspies" — an affectionate moniker that's increasingly coming to be used to refer to those with Asperger's syndrome, a high-functioning form of autism.

Yet despite the problems, and considering his cognitive gifts, there's a good chance that this boy will integrate successfully into society and lead a fulfilling and meaningful life. That's what a growing segment of the autistic community wants the rest of society to acknowledge. Organising around the idea that their condition is not so much a disability as a valid mode of psychological being, a growing number of autistics say that the problem is not with their condition but with the general unwillingness to accept and integrate them into society. Moreover, because of their enhanced cognitive skills, many autistics consider themselves to be the way of the future. In a world where science, programming and math skills are increasingly desirable, where pending neurosciences promise diverse modes of consciousness and psychology, and where interpersonal shortcomings can be made up with communications technologies and social training, monotone neurotypicality may indeed be on the way out.

Historically, autism and Asperger's have always been with us. It's only now that we've got fancy names to describe them. While never officially diagnosed as having autism, a number of historical figures are highly suspected of having it. Newton, Nietzsche, Einstein, Turing and Wittgenstein are seminal thinkers who all exhibited autistic-like traits. In the arts, Jane Austen, Beethoven, Mozart and van Gogh also likely had autism. And today, prominent figures such as Bob Dylan, Woody Allen, Keanu Reeves, Al Gore and, of course, the poster-boy for high-functioning autistics, Bill Gates, are all suspected of having autism. Clearly, autism does not necessarily adhere to its reputation as debilitating affliction. The 1988 film Rain Man, in which Dustin Hoffman portrays a highly disturbed autistic man, has unfortunately coloured much of the popular conception surrounding the disorder, offering most people the sense that autism is in all cases quite severe. Once thought to be a psychiatric disorder, autism is now known to be neurological despite its psychological characteristics. It is a neural condition that falls within the spectrum of pervasive developmental disorders, having considerable variability in terms of its effects on those who have it. Occurring more frequently in boys, common traits include difficulties with emotional communication and social relationships. Autistics tend to have problems with hypersensitivity to incoming stimuli (such as sound and light), and tend to exhibit patterns of behaviour and interests that are uncommon for "neurotypicals" (that is, non-autistics).

With the high-functioning Asperger's - a kind of autism-lite - those who have it tend to have higher than usual intelligence often accompanied by cognitive gifts. Children are likely to develop sophisticated and precocious language skills at an early age. They have excellent spatial and geometric awareness, excellent rote memory skills and become intensely interested in one or two subjects. But true to their autism, Aspies tend to have difficulties understanding nonverbal communication. They tend to comprehend everything literally and have social interaction problems. Additionally, they tend to engage in repetitive activities, have difficultly maintaining eye contact, and have poor motor coordination. In other words, they're nerds.

There is considerable debate as to the causes of autism, but a strong case can be made for there being a genetic component. Ongoing research is focusing on finding the markers that determine autistic phenotypes, but such markers may never be found. Most autistic children, for example, tend to have neurotypical parents, throwing a wrench into the whole genetics angle. One fascinating possibility was expounded in a 2001 Wired article, "The Geek Syndrome," which noted the disproportionately high number of autistic children living in Silicon Valley. The author, Steve Silberman, suggested that its residents, many of whom work in the computer industry, tend to have above average intelligence and gravitate toward tech jobs. Consequently, there is a greater chance that nerdy parents will pair off and have children in Silicon Valley - a phenomenon that Silberman argues may be a facilitating factor in the rise of Asperger's.

As with the cause of autism, there is uncertainty and controversy about whether the incidence of autism is increasing, or if there's simply an increase in the number of reported cases. If the actual incidence is rising, then environmental factors may be playing a part. Or, it could be that parents who produce autistic children are pairing off more frequently, with, as Silberman suggests, some kind of strange selectional effect coming into play. Still, critics argue that it's the increased tendency to diagnose autism that's on the rise, which explains the increase in reported cases. More teachers, clinicians, parents and doctors are aware of the condition, they argue, so diagnoses are more likely. But in North America, studies are showing that the incidence may in fact be rising, growing from one in 5,000 to one in 150 to 400 in the last few years. Other investigations show an increase in autism of 173% in the past decade.

Whether one believes that incidences of autism are on the rise, or that it's the detection of the condition that's on the increase, one undeniable fact is that in a relatively short period of time an identifiable autistic community has emerged. And as with any definable group, it has organised and is starting to fight for what it believes is right. The spark that kindled the autistic rights movement was lit by Jim Sinclair (who has autism himself) in a speech he gave at the 1993 International Conference on Autism in Toronto. Later adapted to the article "Don't Mourn for Us," Sinclair's speech argued that an unnecessary stigma had been attached to autism - a stigma that had resulted in nothing less than discrimination against individuals endowed with an entirely valid mode of psychological being. "Autism isn't something a person has, or a 'shell' that a person is trapped inside," wrote Sinclair, "there's no normal child hidden behind the autism. Autism is a way of being. It is pervasive; it colours every experience, every sensation, perception, thought, emotion, and encounter, every aspect of existence. It is not possible to separate the autism from the person - and if it were possible, the person you'd have left would not be the same person you started with." The tragedy, said Sinclair, is not that autistics exists, but that the world has no place for them to be.

High on the agenda of concerns was, and still is, the "treatment" of autism. The use of drugs, for example, is widely disputed - an issue that, for autistics, brings to mind the use of drugs to "treat" homosexuality last century. Many autistics, including their concerned parents, are becoming increasingly wary of using psychopharmacology and neuroleptic drugs. They argue that autistic people are not psychotic, particularly anxious or depressed. Consequently, the group Autistic People Against Neuroleptic Abuse was organised to counter the tendency. Another controversial form of treatment is applied behaviour analysis (ABA). This treatment involves the training of autistic children through trials and negative and positive reinforcement of tasks that grow in complexity over time. Some, such as Dawson, say this is tantamount to abuse and demand that it be stopped. Autistic activists are essentially anti-cure and anti-therapy, while being pro-education and pro-integration. They construe attempts to weed-out autism as a kind of genocide - as a way to enforce neurotypicality on the entire human populace. As an alternative, these activists demand opportunities for autistics to apply what they see as their unique skills and perceptions. Given the current employment landscape, this is not an entirely unrealistic goal. Aspies in particular seem almost hardwired for certain jobs. In fact, some employers are coming to realise that there may be a benefit to hiring them for particular positions. Detail analysis, for example, tends to be problematic for neurotypicals, whereas scenario analysis is difficult for Aspies. Fast response to individual stimuli is difficult for neurotypicals, while handling long sequences is problematic for Aspies. And typical impulse-driven Aspie conversation causes problems for neurotypicals.

It's been said that the autistic brain works much like a computer, which may in part explain the tendency towards IT and programming jobs. Silicon Valley, as already discussed, is a haven for those with autism. Similarly, Temple Grandin once remarked that NASA was the largest sheltered workshop in the world. As Steve Silberman noted in his Wired article, working in "a WYSIWYG world, where respect and rewards are based strictly on merit, is an Asperger's dream." With the rise in diagnoses, in conjunction with an increase in activism and social opportunities, it comes as little surprise that some autistics see their ilk as a precursor to the future human. Transhumanists, after all, speculate about the rise of the cognitively enhanced posthuman. Enhancement is already here today, argue the autistics, in the form of autism and Asperger's. Moreover, human intelligence appears to be increasing naturally. The so-called Flynn effect reveals that human IQ is increasing at a rate of 3 points per decade (although the cause appears to be mostly environmental). This does bring up an interesting point about the growing presence of valid alternative psychologies and the recurring societal tendency to counter the phenomenon by defining and enforcing some sense of psychological normalcy.

As with human wellness and morphology, neurology is set to come increasingly under each person's control. Given the impetus to explore the wide potential and variability in human cognition, it will be through such things as genetic engineering, neural interface devices, cybernetics and neuropharmaceuticals that a steady diversification of cognition and consciousness will occur; in short order there will be a pluralisation of psychological modes of being — much more than just the autism/neurotypical divide. As a result, different people will process their environment and live their lives in a far more diverse manner than they do today. True to the general imperative to pursue happiness, future humans will explore and expand the conscious space within which they reside and function in hopes of living a meaningful and experiential life. The age of the neurotypical, as much as there ever was such a thing, will soon become a thing of the past.

And as the autistic community is showing, acceptance and accommodation of the psychologically different is a must in a society that values human diversity and potential. So my 7-year-old friend, who only recently received the diagnosis of Asperger's, has a lot to look forward to.

George Dvorsky is the deputy editor of Betterhumans and the president of the Toronto Transhumanist Association, a nonprofit organisation devoted to encouraging the use of technology to transcend limitations of the human body. He currently serves on the Board of Directors for the World Transhumanist Association and the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies. For more Dvorsky, visit his transhumanist blog, Sentient Developments. You can reach him at george@betterhumans.com.

Source: betterhumans.com 3 January 2005

See also:

| Pointing the Finger - The "extreme male brain" theory of autism: Autism - which is, in any case, much more common in men than women - may simply be an extreme magnification of traits, such as problems with communication and empathy, that psychological testing has shown (to the surprise of few women) are more frequently found in men... | |

| Morality and the Brain (earlier in this section) - particularly the article midway down the page entitled "Perspective on Imitation: Empathy and Criminal Responsibility" which discusses the important difference between autists and pschopaths. | |

| I'm Not Guilty but My Brain Is (also earlier in this section) - If no one is responsible for their actions (because we don't really have free will), then NO ONE should be punished. But the fact that people are punished isn't the punushers' fault - they can't help themselves either... (The bottom article, A Mirror to the World, contains more information about autism.) | |

| The Key to Genius - Matt is a 12-year-old autistic musical savant... |

![]()

For articles on bacteria, centrioles, chairs, nebulae, asteroids, robots, memory, chirality, pain, fractals, DNA, geology, strange facts, extra dimensions, spare parts,

discoveries, ageing and more click the "Up" button below to take you to the Table of Contents for this Science section.

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment