Science and Longevity

The Secret of "Muscular" Old AgeI have flabby thighs, but fortunately my stomach covers them. - Joan Rivers

Maintaining muscle mass is easier when young Scientists believe they have found a way to enable the elderly to maintain muscle. Muscle is constantly being built and broken down, which works to maintain a balance in young adults. But as people age, the breakdown process is more successful than the muscle-building action. However French researchers, writing in the Journal of Physiology, say adding the amino acid leucine to old people's diets could help them keep muscle. UK experts agree, saying the best way to boost leucine levels is to eat meat. Once adults reach 40, they start to lose between 0.5 and 2% of their muscle each year. The team from the Human Nutrition Research Centre of Auvergne, in Clermont-Ferrand, France looked at the behaviour of proteins in muscle. As in all mammalian tissues, proteins are created (synthesised) from amino acids and digested (degraded) by enzymes. Straight after a meal, the rate of synthesis doubles, prompted by the arrival of a large amount of amino acids. The rate of the breakdown of protein is highest in-between meals. The difference between the two rates determines how much protein remains in the muscle. But, in older animals - and, it is believed, includes humans - the amino acid stimulus prompting synthesis is less effective, and the process slows down. However, the breakdown of proteins is not, leaving older animals with less protein than their younger counterparts. The researchers compared protein breakdown in young (8-month-old) and old (22-month) rats. They discovered that the slow down in degradation that normally follows a meal does not occur in old animals, so there is excessive breakdown. But when the scientists boosted levels of one amino acid, leucine, the balance of synthesis and breakdown was restored. The team, led by Dr Didier Attaix, suggest the protein processing imbalance which comes with age results from defects in the complex machinery that breaks down muscle protein, and that leucine supplementation can fully restore correct function. He said: "Preventing muscle wasting is a major socio-economic and public health issue, that we may be able to combat with a leucine-rich diet." Dr Michael Rennie from the University of Nottingham Medical School at Derby told the BBC News website said more research into the finding was needed. But he said older people could make changes to their diet now which could help them maintain muscle. "If they don't, they can fall over more easily; they can trip downstairs or fall in the bath." Dr Rennie said older people could act now, even before further research had been carried out. "Leucine is most abundant in meat, so it makes sense in terms of protein synthesis to eat meat. As people get older, they tend to need to eat less. But people should maintain their protein intake as they age." Source: news.bbc.co.uk 11 December 2005

Vanishing Flesh: Muscle Loss in the Elderly Finally Gets Some Respectby Janet Raloff If you're 35 to 40, although you're feeling fit as ever, you have probably begun losing skeletal muscle, the tissue that provides your strength and mobility. Slow, inexorable muscle wasting occurs even in healthy individuals who engage in regular aerobic exercise, but it usually goes unnoticed for decades. In fact, the body hides its loss by subtly padding affected areas with extra fat. So maintaining your weight perfectly over time does not mean muscle isn't vanishing, notes Steven B Heymsfield of St Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Centre in New York. This phenomenon didn't even have a name 8 years ago. At that time, while speaking at a conference on ageing, Irwin H Rosenberg wondered aloud whether its anonymity accounted for the paucity of research on it - and for the medical community's apparent lack of concern over its role in crippling society's elders. Several recent studies have indicated that while thinning bones render the elderly especially vulnerable to fractures, it's the unsteadiness caused by muscle wasting in the legs that leads to falls. To the extent that it makes walking, stair climbing, and getting in and out of chairs difficult, muscle loss can not only rob ageing adults of their independence but also steer them into unhealthful, sedentary lifestyles. "So that we could begin taking this problem seriously, I suggested, half tongue in cheek, that we give it a name - sarcopenia," recalls Rosenberg, director of the Agriculture Department's Jean Mayer Human Nutrition Research Centre on Ageing at Tufts University in Boston. He hoped the Greek moniker's classical ring would give it the cachet to catch on. The tactic worked. Sarcopenia, which means "vanishing flesh," has begun popping up in medical texts and gerontology papers. It even appears in a solicitation for new research proposals just issued by the National Institute on Ageing (NIA) in Bethesda, Maryland. The institute convened a conference 4 weeks ago on techniques for studying sarcopenia, with the goal of spurring more research in the area. Next spring, NIA plans to launch an 8-year study of how this muscle loss affects activity and recovery from disease in 3,000 otherwise healthy septuagenarians. At its annual meeting in October, the American Ageing Association has scheduled a session on sarcopenia. And Miriam E Nelson of the Tufts centre has written a book for the general public, due out next year, describing exercises that her studies show can fight the ravages of muscle loss.

Grandmaster Tingsen Xu teaches Tai Chi Quan, a balance-enhancing exercise, Sarcopenia is well on its way to becoming a household word, like osteoporosis, concludes geriatrician Tamara Harris of NIA. Gilbert Forbes of the University of Rochester (New York) School of Medicine holds the world's record for the longest chronicle of age-related muscle loss in a single individual. Since he was 44, Forbes has measured his own fat-free mass on at least 150 separate occasions spanning 37 years. He has another 27 years' worth of data on a colleague, begun when that man was 53. Skeletal muscle comprises about half of a person's lean body weight. Because the weight of the two other major components - bone and viscera (organs) - does not drop much over time, Forbes' measurements offer an indirect gauge of vanishing muscle. Those data, reported at the Experimental Biology '96 meeting in Washington DC, this past April, indicate that Forbes experienced a fairly constant 1 kilogram per decade loss of muscle, roughly twice the rate of his heavier, more muscular colleague. To get a speedier estimate of sarcopenia within the general population, Ronenn Roubenoff and Joseph Kehayias of the Tufts centre have just finished measuring skeletal muscle in Boston area adults. By comparing people of different ages but similar builds, they're looking to identify when muscle loss begins and how quickly it proceeds. The data we have clearly show a decline from the thirties onward," Roubenoff said. Though men tend to start with more muscle, they appear to lose about the same percentage as women over time. Despite large individual variability, he says, the trends indicate "that if you're a healthy elderly person in your seventies, you're down about 20% [in skeletal muscle] from where you were at age 25 or 30." Moreover, there are some indications that sarcopenia's ravages accelerate with time. So far, these associations "are primarily anecdotal," Harris says. However, she adds, there haven't been many attempts to look into it. Eric T Poehlman of the Baltimore Veterans Affairs Medical Centre and his colleagues are among the few who have tackled this question. They reported finding just such a trend in the 1 November 1995 Annals of Internal Medicine. For 6 years, they followed 35 healthy but sedentary women who were in their mid to late 40s at the start of the study. The investigators monitored such factors as physical activity, calories burned during periods of rest, and where their bodies store fat. Over this period, half of the women entered menopause. While all the volunteers maintained a fairly constant weight, those who became menopausal lost an average of 3 kg of lean tissue during the study, 6 times the loss seen in the women of the same age who did not enter menopause. The menopausal women also became less active over the course of the study, a factor that can itself spur muscle loss. This study didn't continue long enough to establish whether the acceleration of sarcopenia at menopause represents a permanent change. But Poehlman says his data clearly indicate that menopause "throws you into a downward spiral of muscle loss and inactivity - two things you don't want to happen." One hallmark of menopause is a drop in a woman's production of the sex hormone œstrogen. Might such a change accelerate sarcopenia? "It's possible," says endocrinologist Clifford J Rosen of the Maine Centre for Osteoporosis Research and Education at St Joseph Hospital in Bangor. Œstrogen helps modulate the body's production of a hormone, insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1), that is important for muscle growth and development, Rosen notes. Growth hormone controls concentrations of IGF-1 even more directly. Like œstrogen, growth hormone declines dramatically with age in both men and women. Rosen therefore suspects that age-related drops in growth hormone, œstrogen, and other hormones may play a driving role in sarcopenia. To test that idea, he's conducting a year-long trial with 200 frail men and women over the age of 65. Half receive daily supplements of growth hormone, the others a placebo. If the study shows that the treatment halts muscle loss or aids an individual's ability to regain muscle strength with exercise, it may hold out the prospect of hormone therapy, he says. Charlotte A Peterson of the McClellan Memorial Veterans Hospital in Little Rock, Arkansas, suspects that some share of sarcopenia may also trace to problems involving satellite cells, the body's poorly understood muscle repair crews. Her data indicate that here again, IGF may play a role. A large community of these satellite cells surrounds skeletal muscle. They do nothing until a muscle needs to grow or experiences damage - such as a bruise or those minor rips that cause aches the day after exercise. Then the satellite cells spring into action, migrating to where they're needed. Some multiply and turn into new muscle, which eventually fuses to the old muscle. Others return to their quiet state to await the next crisis. "We're trying to figure out what signals which satellite cells to do what," Peterson explains. What is clear, she says, is that the performance of satellite cells wanes with age. Her work with rats has shown that within just a few weeks, muscle damage in a 3- to 6-month-old young adult completely disappears. But when an elderly 24- to 28-month-old animal sustains the same damage, the satellite cells' repair proceeds much more slowly and often incompletely. The real problem, she notes, may be not the satellite cells themselves but rather the body's difficulty in communicating with them. Other researchers have shown that when they transplant muscle and its satellite cells from an old animal into a young one, the muscle again heals rapidly. Insulin-like growth factors "seem to be really important in controlling satellite cell function," Peterson says. Her preliminary evidence indicates "that satellite cells from older animals mount a less robust IGF response following injury." This suggests, she says, "that it's production of the growth factor that may be impaired."

Magnetic resonance image of a thigh cross section from a 25-year-old man (left) and a Age-related neurological changes may also play a pivotal role in sarcopenia. Over decades, the body loses nerves, including those that branch out from the spinal cord into skeletal muscle throughout the body. As one of these nerves dies, a neighbour sends out branches to rescue the muscle fibres that had been abandoned. Without such a new nerve connection, that muscle would eventually shrink and die. But there's a limit to how much a nerve can grow, according to studies by neurologist Jan Lexell of Lund University Hospital in Sweden. "It's somewhere around two to three times its original size," he says. "So it can double the number of muscle fibres that it innervates" but probably no more. When surviving nerves are no longer numerous enough to rescue all of the abandoned muscle fibres, he says, sarcopenia becomes inevitable. Studies that have attempted to quantify the loss of these muscle-innervating nerves find that somewhere between ¼ and ½ of them die off between the ages of 25 and 75. Moreover, Lexell observes, because the rate of nerve loss "speeds up after age 60," persons approaching 90 are likely to have suffered dramatically more loss. His studies indicate that the first muscle fibres to go are those used the least - rapidly-contracting fibres that serve as a sort of muscular overdrive. The body calls on them to execute the most intense and rapid activities, such as heavy lifting and sprinting. The progressive loss of different types of muscle "accounts for part of the slowing of our movements with age," he says, and much of the frailty. What all these studies confirm, Rosenberg maintains, is that although sarcopenia may represent a universal symptom of ageing today, it should not be accepted as normal. Instead, he argues, it should be considered a newly recognised disease - amenable to prevention and treatment. In fact, a series of studies at his centre indicate that exercise regimes that focus on high-intensity resistance training of the arms and legs go a long way toward countering disabling frailty in the elderly. Lexell agrees, noting that this type of exercise wakes up languishing overdrive muscles by challenging them to gradually and steadily lift or move increasingly heavy weights. "Older people who have done weight lifting over the last 15 to 20 years will have muscles the same size as someone who is 20 and sedentary," he notes. It's never too late to start that muscle training, according to studies over the past few years led by Nelson and Maria A Fiatarone of the Tufts centre. In one 10-week study of 100 frail nursing home residents between the ages of 72 and 98, individuals more than doubled the strength of trained muscles and increased their stair-climbing power by 28% when they exercised their legs with resistance training three times a week. Nelson's group then prescribed a less rigorous training regimen, with workouts only twice a week, in a year-long study with 50- to 70-year-old women. Not only did those who exercised increase their strength throughout the study, but they also gained skeletal muscle. Women who remained sedentary declined on both measures. Moreover, this training offers payoffs that go well beyond sarcopenia, notes William J Evans of Pennsylvania State University in University Park. A physiologist, he collaborated with the Tufts team on several of their exercise studies. While those women assigned to an exercise group in the year-long study gained a little bone over the course of their training, he notes that those who remained sedentary lost about 2% of their bone. In another study, his group found that elderly men and women who performed strength training for 3 months burned 15% more calories over the course of a day than their sedentary counterparts. The difference was traced not so much to their increased exercise but to a boost in their metabolism, which should fight sluggishness and weight gain, he says. In fact, he notes, those elderly adults who follow through on weight training tend to voluntarily increase their activity. In some cases, this training also enabled them to forsake wheelchairs for a walker or cane. That's one reason the Tufts centre is fighting sarcopenia so actively, Rosenberg says. Muscle loss is robbing the elderly of their freedom. "We want to give it back." Source: sciencenews.org Science News Vol 150 10 August 1996 photo credit Steven L Wolf / Emory (Tai Chi) and Jubrias & Conley / University of Washington Medical Centre

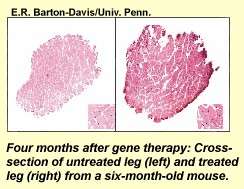

New Gene Therapy Fights Frailtyby Janet Raloff By age 40, every man and woman begins losing muscle. Over the next 3 to 5 decades, this process - known as sarcopenia, or "vanishing flesh" - inexorably transforms even the most hale individuals into frail elders. While exercise can slow the weakening that accompanies this loss, there has been no way to halt the muscle wasting. New research now suggests that this unrelenting process may be stoppable. Working with mice, which experience a similar loss of up to 30% of their skeletal muscle during ageing, scientists applied a novel gene therapy. They inserted DNA for a hormone-like substance into a virus gutted of the capacity to cause disease. The researchers then injected the virus into the right, back leg of young, middle-age, and elderly animals. They then observed the rodents, which were kept sedentary, for 3 to 9 months. Comparing the treated leg with its left counterpart, they found roughly 15% more mass and strength in the right leg of young adult animals. In geriatric mice, the effect was even more pronounced: they showed 19% more muscle mass and 27% more power in the treated leg.

"Though I expected improvement in the old animals, I never dreamed we would basically preserve them at young-adult levels," says study leader H Lee Sweeney of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia. His team presented its findings 14 December at a meeting in San Francisco of the American Society for Cell Biology. A report of the work also appears in the 22 December Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Previous studies suggested that sarcopenia might trace to a drop in the body's production or ability to use insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1), explains Anna M McCormick of the National Institute on Ageing in Bethesda, Maryland. Normally secreted by injured muscle, this hormone-like substance recruits nearby satellite cells - local repair crews - to mend routine, small muscle rips. The new findings don't prove that an IGF-1 deficiency causes sarcopenia, says Nadia Rosenthal at the Cardiovascular Research Centre of Massachusetts General Hospital in Charlestown, a member of Sweeney's team. However, she notes, this gene therapy "can arrest [muscle] degeneration and atrophy due to ageing." And while it works in both young and old animals, she says, to get the most benefit, "the younger the better." "This is exciting," says Charlotte A Peterson of the University of Arkansas in Little Rock. "It's the first case of a molecule affecting muscle atrophy due to ageing," she says. The technique used to provide it "is the closest anyone has come to something you might consider using as a therapy [for people]," she adds. McCormick agrees that it's "a great proof of principle. But as with any gene therapy, we have a long way to go." Still, "these dramatic findings signal a fountain-of-youth opportunity," says neurologist Leon I Charash of Cornell University Medical College in New York City. He is a medical advisor to the Muscular Dystrophy Association, which funded Sweeney's team. The finding holds out the prospect, he says, "of helping older people lead healthier and better lives, with less need for medical care." Rosenthal is also excited by the technique's potential use in helping ageing cardiac muscle repair damage from a heart attack. Sweeney notes it may even help limit some of the wasting caused by the milder forms of muscular dystrophy. However, because the treatment's effects are local, treating a human to prevent frailty might require hundreds of injections to augment all the skeletal muscles vulnerable to ageing. Cardiac therapy would need far fewer injections. In either case, Sweeney says, "you'd only have to do it once." References:Barton-Davis, E R . . . N Rosenthal, and H L Sweeney 1998: "Viral Mediated Expression of IGF-1 Keeps Muscles Young and Strong in Old Mice", Meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology, December, San Francisco ______ 1998: "Viral Mediated Expression of IGF-1 Blocks the Ageing-Related Loss of Skeletal Muscle Function", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95 (December 22) Sources:Elizabeth R Barton-Davis Leon I Charash Anna M McCormick Muscular Dystrophy Association Charlotte Peterson Nadia Rosenthal H Lee Sweeney Source: Science News, Vol 154, No 25 & 26, 19 & 26 December 1998 © Science Service

No Exercise Earns You Browniesby D J Griffin They're determined. Dedicated. Relentless. In the unforgiving cold of winter, you see them on the roadside - usually in early morning or as dusk falls. They have pained, nauseated expressions. Steam rises from their mouths. Mittens, caps and reflective gear protect them from frigid temperatures and speeding traffic. They're the joggers and bikers bound to complete their daily workout - no matter what the weather. I'm not one of them. In fact, back when Christmas neared and darkness prevailed, I happily rolled my bike into the garage, pulled down the door - and took up the easy game of helping my family convince me to stay put. I recommend the balance highly: express good intentions. Then, bask in praise for doing nothing. Little work. Big satisfaction. Here's just one example of a flawlessly executed play: One evening, as a blur of headlights breezed through the darkness at the end of our driveway, I stood up, stretched my arms and made the announcement. "I think I'll go out for a long walk," I said. (To get the ball rolling quickly, it's crucial that your stated good intention be reasonable: suggesting a pitch-black bike ride would have made the bluff too easy to spot.) "Oh, stop that talk!" my mother said, crunching the obituary page in her lap and wrinkling her forehead in concern. "It's too dark! You'll be killed! And we need your paycheque. Now, be a good boy and sit back down." "No, no," I said, broadly, while I stretched again. "I have to stay healthy. I want to live a long time." "You don't have to exercise to live a long time," 10-year-old son Andrew said. "Look at grandma: she doesn't do a thing - and she's older than dirt." "I am not!" she protested. "I'm only 39." "That's younger than daddy," 10-year-old son James observed. "How could you have a kid before you were born yourself?" "Well," she said. "I did. And now he's going to worry his poor mother to death by walking out in the traffic when it's dark. He must have gotten his lack of judgment from his father." (I've heard this routine more often than North Andover's unrepentant cries for financial salvation.) "He certainly didn't get it from my side of the family..." This was too easy. "I'd better get going," I told her. "I want to be back within a few hours. I might even walk over to CVS in Andover and pick up your prescriptions." "Walk across Route 125 traffic!" she exclaimed. "Oh, please don't! Who'll drive me over to Breen's the next time one of my friends is laid out? You're such a heartache. If you only knew!" I sighed. "Would my going out really worry you that much?" I asked. "It certainly would," she said. "In fact, if you promise not to go, I'll even get out the brownies I baked and hid this afternoon." "Well," I said, victory at hand, "I wouldn't want to worry you. And I suppose I could eat a brownie - but just one." "Stay right there," she said. "I'll be back in a minute - if I could only remember where I hid them." "In the hutch in the dining room," James responded, as his big sister rushed in. "Daddy," she said. "Mommy and I have decided to go up to the MSPCA and get a dog. We saw a big one up there that we all liked." "Oh, no," I said. "Not a dog! Anything but a dog! It'll jump all over everything and make a mess. Aren't a cat and a hamster enough?" "Well," she said, retreating a bit. "Then, how about a chinchilla? It's small. It lives in a cage. It even bathes in dust." And so it does - right down in the basement playroom. Kids are so manipulative. Where do they learn these tactics? I'm still trying to figure it out. D J Griffin heads The Eagle-Tribune's Andover (New Hampshire) Content Group, a commercial communications and marketing company based in North Andover's Old Centre. E-mail him at dgriffin@andovercontent.com. Source: eagletribune.com Monday 4 February 2002

For articles related to ageing, including feats that can be accomplished, and a non-spiritual look at what happens after death - funerals, jerky, popsicles, fertiliser, ashes, orbit or dust - click the

"Up" button below to take you to the Index page for this Older and Under section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment