How Do I Know When I Get There

Getting OldOld age is not a disease - it is strength and survivorship, triumph over all kinds of vicissitudes and disappointments, trials and illnesses. - Maggie Kuhn by Norm Wallen This is about one (male) person's experience with getting old. I don't know whether it fits anyone else, but I don't think that I'm (that) unique. I don't much like caveats, but here's one anyway. I've read little of burgeoning literature on aging - for two reasons: one is my propensity for denial - which I'll get to presently - the other is that when I have read some it made me want to vomit. So, what follows is my understanding of what has happened to me. I hope you find it useful; if not, at least entertaining. If neither, well - to hell with you. My old age started at 60. Well, almost. My 50th birthday was awful but the metaphor soon passed and my attitude remained basically denial. I know denial is supposed to be unhealthy - leading to all kinds of unconscious irrational side effects. Actually, I believe it's true, but what is overlooked are its advantages - in relation to aging. Consider the alternatives: compensation and acceptance. Compensation says, Okay, so I can't do what I used to; I'll do other things instead. Bullshit! Basketweaving instead of basketball? Hiking instead of skiing? Ping-pong instead of racquetball? Repairing the bird feeder instead of the roof? Forget it! Acceptance. Even worse. Just eat it, fella. Don't mind that you can't do what gave you joy. Accept the fact that it's over - or almost. Why? So you can drift, uncomplaining into becoming a vegetable? Or so you can appreciate the delights of aging? Fine - what are they? Sit back and bask in your accomplishments. Great, if you are sufficient fool to really believe it. In reality, our triumphs, if any, are trivial. Especially in an era when nothing is sacred. Who knows whether science is - finally - a good thing? Whether what we have tried to teach, as teachers, parents, friends, or citizens, has any real value? Good Lord, even making money is no longer universally worshipped. We can, being human, kid ourselves into comfort - but for how long? Better to deny those protesting muscles and neurons and keep on keeping on. The joy is, after all, in the anticipation and the doing, not the reminiscence. Up to a point. My point was around 60. Denial finally failed me. I could no longer switch quickly from one topic to another; I had to recognise the slippage. Naturally, I saw it first in others - "Come on John, we decided that 15 minutes ago!" Getting up to make a point and finding the words wouldn't come. Next, the body. Packing and moving put the final touches on my unsuspected sciatica, curse of the careless. Screw denial, this hurts. Not a whole lot; just enough. So, now what? I really don't regret my denial strategy though I might have paid a little more attention to my body. There's nothing I could have done about my brain. It seems I have no choice but to pay attention, pace myself, parcel out my physical and mental energy and try not to do anything too stupid. I want to be able to walk in the wilderness, to participate in the world and to copulate once in awhile without seizing up. There are a few good things. I no longer have to compete, to prove anything and that's a relief. Time with children and friends is good but never enough (the endless wail of us seniors). There is satisfaction in achieving, at last, a sizable measure of marital understanding. And there is considerable pleasure in getting away with speaking my mind. You really can get away with a lot once you acquire "old fart" status. Just think how marvelous it would be if AARP became "Old Farts United" (and quit selling out). I figure another ten reasonably good years. Unavoidable deterioration but, hopefully, no major catastrophe. After 75 scares me. Not dying, mostly. Every so often the thought terrifies me; none of the available condolences works and I can't conceive of being non-existent. But most of the time I accept (how about that?) the inevitable. What really scares me is the prospect of living my last few years and dying the way my parents did. I would like to age gracefully, as I imagine Katherine Hepburn and William 0 Douglas have, and as a woman I know actually did. I would like to tell my experiences in a useful way as Indian elders are supposed to. And I want to know when I have become a burden to those who love me. Long before the catheters, forced feeding and all the rest Long before it costs somebody $3,000 a month to keep me in one of those nursing facilities where the only signs of real life (in a good one!) are among the staff. And this when we have children going to bed hungry! I want to know when I can no longer feel joy or produce it in others, and I want to be able to end it with dignity. God forbid a mind-destroying tumor or stroke (or whatever) that modern medicine is so pleased to deter from its natural course. I have long thought the "primitives" knew better. When you can't keep up, be left with a blanket, a little food and some dope. Since we are too civilised for this, maybe denial - to the end - makes more sense. Source: Anderson Valley Advertiser, Boonville, California 94515 30 August 1995

Downhill from HereMy parents didn't want to move to Florida, but they turned 60, and that's the law. - Jerry Seinfeld. by Darryl Reanny A person who is able to say "I'm not worried by the thought of death" has usually had little, if any, direct experience of the phenomenon he affects to disregard; by "direct experience" I do not mean the occasional sight of a dead body caused by a car accident or even the sight of a dead relative in a mortuary chapel - I mean an extended and intimate association with a known person through the phases of dying and up to and beyond the actual moment of death itself. To a degree that our ancestors would have found quite amazing, death has, in our time, been taken "offstage," hidden in institutions, and concealed behind closed doors. Most of us go through life and never see death. When we say we are not frightened of death we are, to a significant degree, describing our reaction to an event we have not witnessed, passing judgment on something we do not know. Age 40-50 - The Denial of Time and the Shadow of Approaching Night[This period] encompasses the greatest crisis of the contemporary human life cycle in the West - the period when ageing begins to affect function for the first time, when reproductive capacity usually ends (in women) and when the awareness of death becomes a major psychological preoccupation. Carl Jung summed up the significance of this phase eloquently when he said:

Mental abilities remain sharp and decision-making processes may indeed improve as the weight of a lifetime's accumulated experience optimises the ability to pick "winners" among options offered. However, with the menopause, the female fertility clock is switched off. The emotional aftermath of this in women is well known, often taking the form of a semi-clinical condition called "post menopausal depression." Men may also experience an age-related "mid-life crisis." The key point is that the waning of reproductive fitness cuts the lifeline that links the individual to his/her genetic future. Henceforth, the individual is in evolution's discard tray, unshielded from the fear of death by the inability to beget compensating life. The crisis is focussed by the fact that it often coincides with the highest probability of kin death, that is, it is during the 40 - 50 period that the individual is most likely to experience the loss of his/her parents. Even in today's mobile society, the legal responsibility for disposing of the newly deceased rests with their next-of-kin. Thus [people in this age group] are forced to confront, usually for the first time, the fact of death in those individuals with whom they have the strongest emotional ties. When their parents die, so in literal truth, does a part of themselves. This period also marks the climacteric of life. Increasingly, as the years tick by, the vision of an ever-contracting future impacts fearfully on the present despite the fact that 40 - 50 year-old individuals are still typically fit. Indeed, it is precisely during this interval that men and women often develop obsessive preoccupations with health - jogging, joining fitness clubs, going on diets, undergoing elective surgery, beginning the battle with time which henceforth and increasingly is seen as "the enemy". A noticeable feature of [this period] is the speeding up of inner time. Phrases like "My God, where's the day gone?!" or "The year's just flown!" or "It can't be June already!!" bespeak of an accelerating internal timekeeper. The human brain measures time by the frequency of novel additions to its memory banks, of things that leave a strongly etched memory trace because they do not correspond to any previous experience - things which "stand out". Thus when we are very young, most of the experiences we encounter during the course of a week are new or have some element of newness. This abundance of novel elements fills the daily memory register with "entries" and hence causes our sense of retrospective time to "stretch", that is the day seems longer because it contains so many stored memory traces. As we get older, more and more of life is relegated to the status of habit. We get into our car in the morning without, in an important sense, "seeing" it; we carry an internal model of the car and its various features in our minds. This minimises the amount of conscious attention we have to devote to finding our seats and operating the vehicle. Indeed, the process of driving, once learned, becomes totally habitual and is displaced from the upper story of the brain (the cerebral cortex) into an adjacent brain part (the cerebellum). Repetitive actions and sights do not register in consciousness as the information they carry to the brain is already familiar and the mental route it follows has been "smoothed" (facilitated) by the hundreds of prior "replicas" that have gone before. The upshot of this is that individuals, living and working within the familiar, habitual boundary conditions are largely unaware of perhaps 80% or more of what goes on around them. Consequently, time contracts and seems to run more quickly. Kenneth Kramer, an expert in comparative religion, notes that modern American idiom contains 66 euphemisms which allow individuals to avoid words like "death" or "dying", for example "passed away", "kicked the bucket", "checked out", "gone to heaven", "breathed the last", and so forth. Paradoxically, this denial of death also applies to the person who is dying. It is significant, for example, that behaviour-modifying drugs have become an integral part of the contemporary dying process. Opiate-type pills including morphine and heroin are given to relieve pain. While few would quarrel with the goal of minimising suffering, it is also true that these drugs affect brain chemistry in such a way as to "soften" reality. It can be fairly said that most people who die in hospitals are physiologically prevented from "experiencing" death in any meaningful sense. The realisation that a vacuum contains an infinity of virtual particles embedded in a foamy spacetime matrix makes the next feature of the vacuum slightly easier to comprehend. Richard Feynman has suggested that every cubic centimetre of vacuum contains enough energy to boil all the oceans on earth. Arthur C Clarke puts it even more forcibly:

The human anguish that the fate of the cosmos engenders is summed up by American cosmologist Steven Weinberg near the end of his book, The First Three Minutes: The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless. The ego-self is a symbolic point of internal reference, a nexus created in the mind by the mind to organise the input of experience so as to preserve the coherence of the subjective realm and allow the body/self to function in a purposeful way. We must ask not what the ego-self is but how it comes into being. Our sense of ego arises by a process of differentiation which progressively separates each of us from the rest of humanity. The net result of this process of differentiation, simplistically put, is that the ego becomes the sum of our differences. The process of differentiation that creates ego begins before birth. Each ego is given a strong "weighting" by the genes it inherits from its parents which predisposes mentality to grow around certain predetermined lines. Each ego also has to undergo a common rite of passage into being, emerging from a sense of primal unity with the Mother into a sense of precarious independence, when it feels fearfully "on its own". But once "in the world," what builds ego is the differentiating process involving human choice. "The ego is the product of choices." Initially, however, those choices are not its own. When we are children, for example, we usually cannot dictate the choices our parents make. As we grow up, it is the effects of the many Y node choices made by our parents and others around us that, increasingly and progressively, differentiate us from our fellows; in this process, the ego self emerges. It is not until this ego-self has acquired its own "personality" that we begin to take on responsibility for our own decisions. The ego-self is largely a collection of accidents which separate our minds from those of our fellows. It is a kind of existential "noise" which owes its being in large part to the chiefly random character of the events that create it. As such, the ego-self - the identity tag that our survival loops guard so carefully - has absolutely no value as a window to the world. What makes you unique is not ego-self but quality of consciousness or more precisely the point reached in the scale of mental evolution. Thus two people from the same ethnic and cultural backgrounds, born in the same street, with similar ego-self frameworking can fail to understand each other if their degree of psychological maturity differs by too wide a margin. Conversely, two people from different sides of the globe - an African, say, and a Canadian - can meet and "speak the same language" instantly if their minds have reached the same growth stage, despite radically different ego-self structures. Any human being who has reached a certain point in his psychological development will be able to intuitively "identify with" (telltale term) any other person at the same stage of growth. The stage is what matters, for each grade of consciousness is the same for all the human beings who reach it. In nature, differences, no matter how small, can be a matter of life and death. Differences define fitness to survive. By continually adjusting the fitness of all living systems, natural selection has, across three and a half billion years, honed the survival software of genes, indelibly imprinting the "survive at all costs" imperative on cells and psychologies. Differences drive evolution. By the time we are 13 years old, we normally have strongly developed ego-selves. Significantly, our feelings of protective love tend to be strongest when our children are just that - children. After that, their evolving ego-selves start to differentiate them from us and erect the distinctions that can so bruise interactions among ego-conscious adults. Evolution still works on and through individual differences between people. Some do well, other fall by the way. However, our culture has changed the rules. Success is no longer measured in terms of reproduction but in terms of achievement - often measured by indicators of "status" such as the accumulation of material wealth and power. Differences retain their significance, however because, in our society, in this ego-conscious phase of its evolution, differences fulfil the same competitive "me versus you" function they had in the animal phase. Up to a point, the dynamics of human life are based on the fact that each individual has a different sense of separate ego, of "I am" as opposed to "You are". Thus human society experiences a mode of natural selection based on competition between ego-conscious individuals. What this product selects for is, in the main, what one might expect of such a system: greed, survival at all costs, a "killer instinct" in business, a massive emphasis on goods which reflect enlarged ego structures, wealth, power, indifference to others - in short, selfishness. Selfish egos replace selfish genes. What we dread above almost all else is change. By this, I do not mean the addition of ordinary day-to-day experiences which are easily accommodated within the existing ego-self structure; I mean changes that profoundly alter the ego-self, reshaping and remaking it. If we change the "I" self-image too deeply, we create a new creature; the "me" that emerges from a profound personality change is, in a real and factual sense, no longer me - it is a stranger, it is other. For this reason, a defining feature of human growth, the transformative experiences of life, those which involve suffering and pain, and "shake us to the core" are innately resisted. Any advance in knowledge which strengthens man's power weakens the fit between man and the natural order from which he arose. Deep changes in personality can kill the ego-self, that is, cause the sense of separate self to die. Unlike physical death, however, a significant ego-death is a rite-of-passage. Through ego-death, the old "me" is destroyed and the circuits of the mind spontaneously rearrange themselves into a new stable state, centred on a new but different me. Primitive cultures have always understood the transformative power of a rite of passage. Puberty rites among Aborigines mark the end of boyhood and the taking-up of adult status. They recognise the need for pain in these rituals, using the agony of circumcision and the terror of the unknown to rework the consciousness of the initiate, "burning out" the outgrown psychology of boyhood to lay the ground for the new psychology of manhood. In primitive cultures, the terror evoked by a rite of passage is offset by the group context in which it takes place. The boy initiate is not alone in the night of his fear. Modern man has, however, no such safety net of ritual and shared experience. With a few rare exceptions, we must face our rites of passage alone. This is one reason why, for the most part, we fail to enter any transformative process. We dread deep, non-pleasurable experiences that could transfigure our personalities more than we dread almost anything else in life. We sense their power to destroy us, which they can. We see them as death, which they are. Yet, it is only through experiencing psychological death that we can lose our fear of physical death and break free of time or more precisely, see reality at last. Most of the choices we make limit the universal quality of consciousness. By definition, when we opt for A, we turn our backs on B. Over time, many choices have been made. Through tens of years, we fix the structure of our thoughts in words, and emerge with a tightly defined and narrowly focussed lens on the world. Over time, gradually, irresistibly, inevitably the ego-self becomes a trap for consciousness, a prison in which our vision becomes increasingly ensnared and enmeshed. If each deep memory imprinted on the mind alters the organisation of the brain, over the years of life, the mind must be increasingly "trapped" by the changes that occur in its own physical structure, resulting in an increasingly "personal" vision of reality. For 99% of humanity, the pain and fear involved in ego-death is sufficient to stop the processes of authentic growth at the mid-life crisis. Stalled and thwarted, the psychology of people in their 40s and 50s often turns to displacement or outright regression. The biggest market for teenage prostitutes is middle-aged men; the biggest market for elective surgery to "restore youth" is middle-aged women. As the clock ticks on, people of both sexes increasingly look to the past, not the future, and life takes on a retrospective "if only" flavour long before the effects of ageing start to take their toll. Death itself becomes the one power that can force man to confront mortality in mid-life because it is then that he sees that "the grinning skull" is his own. Only this fear of physical death - the primal terror - can drive him to enter the painful process of inner transformation from which he can emerge free and unafraid. Only the certain threat of physical death, advancing ever closer across life's landscape, can engender the crisis of confidence and conscience that prepares the receptive human mind for possible transformation, for the loss of its familiar signposts, its comforting walls of habit, its backward-looking focus. However, it is a transformation few ever undergo. Source: From The Death of Forever: A New Future for Human Consciousness by Darryl Reanny

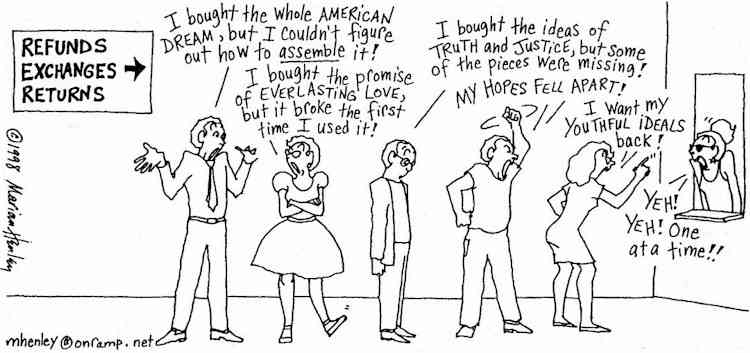

Life's Cumulative Dissatisfactions

Source: Funny Times January 1999 mhenley@onramp.net

Phillip Johnson at 95Old age is like everything else. To make a success of it, you've got to start young. - Theodore Roosevelt

Philip Johnson: Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut 1949

I used to think that each phase of life was the end. But now that my view on life is more or less fixed, I believe that change is a great thing. In fact, it's the only real absolute in the world. Sex isn't of much interest to me anymore, except inasmuch as you enjoy it in a beautiful room better than you do in a dull room. Sex is best in a cocoon. You have to feel wombish. If architects weren't arrogant, they wouldn't be architects. I don't know a modest good architect. Chainlink is hardly a humble material, but corrugated tin doesn't mean anything to me. I don't do a damn thing I don't want to. I wouldn't build a building if it wasn't of interest to me as a potential work of art. Why should I? You're going to change the world? Well, go ahead and try. You'll give it up at a certain point and change yourself instead. Pick very few objects and place them exactly. Faith? Haven't any. I'm not a nihilist or a relativist. I don't believe in anything but change. I'm a Heraclitean - you can't step in the same river twice. I'm not interested in politics, and I'm no good at it. You make mistakes. Walk every day. I got everything from someone. Nobody can be original. As Mies van der Rohe said, "I don't want to be original. I want to be good." I don't think there's any why about art. It's an end in itself. I love money. I could make more beautiful objects if I had more money. But if you think about it too much, then it doesn't help your art. How does an artist know when the line that he just painted is good or not? That's the catch. De Kooning was the greatest of my contemporaries in art, and he knew when he'd done a good line. When he didn't, he threw it away. I wish I'd thrown away some of mine. You get involved and say, well, maybe I can save this building if I do this or do that. Throw it away! A lot of intellectuals are interested in words. Words annoy me. Everybody should design their own home. I'm against architects designing homes. How do I know that you want to live in a picture-window Colonial? It's silly, but you might want to. Who am I to say? Americans like to build on the road. I never could understand it. Architecture is the arrangement of space for excitement. Storms in this house are horrendous but thrilling. Glass shatters. Danger is one of the greatest things to use in architecture. Comfort is not one of my interests. You can feel comfortable in any environment that's beautiful. A room is only as good as you feel when you're in it. If I could build one building in my life, I want to build a building that people feel in the stomach - you can call it comfort, beauty, excitement, guts, tears... There are many ways to describe the reaction to architecture, but tears are as good as any. Put everything away and don't open the closet. Source: Anderson Valley Advertiser 27 January 1999

Skeletons in the ClosetToward the end of his life, Johnson went public with some private matters - his homosexuality and his past as a disciple of Hitler-style fascism. On the latter, he said he spent much time in Berlin in the 1930s and became "fascinated with power," but added he did not consider that an excuse. "I have no excuse (for) such utter, unbelievable stupidity. I don't know how you expiate guilt," he said. He blamed his homosexuality for causing a nervous breakdown while he was a student at Harvard and said that in 1977 he asked the New Yorker magazine to omit references to it in a profile, fearing he might lose the AT&T commission, which he called "the job of my life." In the 1950s, Johnson reflected on his career and what he hoped to achieve. "I like the thought that what we are to do on this earth is embellish it for its greater beauty," he said, "so that oncoming generations can look back to the shapes we leave here and get the same thrill that I get in looking back at theirs - at the Parthenon, at Chartres Cathedral." Johnson died Tuesday, 25 January 2005 at his home in New Canaan, Connecticut, Source: cnn.com

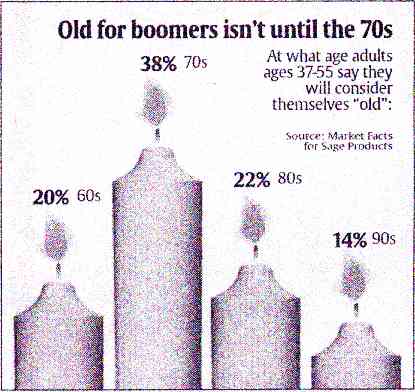

When Am I Old?

Source: USA Today Wednesday 18 April 2001

How Much Time Do I Have Left?If you mean statistically, visit deathclock.com which will compute how much time you have left based on your birthdate. Or visit test.thespark.com/deathtest which does the same, only it tries to be a bit more accurate by asking for more information.

Grit and Wit of Last ResortEvery once in a while you're you're walking down the street and you catch a glimpse of yourself in a store window and you go, - Jessica Lange by Jane Bowron The end game. It's anathema to the West. Everybody fears it, but the troopers in The Last Resort, a brilliant documentary about the lives of 300 old timers dodging the grim reaper in a retirement village in Waikanae, faced the end game with true grit and wit. Because those in the twilight years have been so marginalised and forgotten in a society obsessed with youth and vigour, the spotlight has rarely shone on the elderly and their lives. Instead of looking at past achievements, this documentary focused on what was going on now in the golden oldies' lives and their take on coping with growing older and facing death, the ultimate challenge. The retirement village, billed as one of the top 10 in the world, a sort of Club Med for the wrinklies, was a place of sanctity where there was a reasonable level playing field for the inmates to still have a vital life. Nancy, who the documentary was dedicated to, was in her 90s and had lived in the village for 10 years and never really liked it but put up with it. What this motorised and dignified old battler found most disconcerting was being in the company of the bewildered, whose minds had faded and who, like a shot-to-hell Greek chorus, continually asked Nancy what her name was. "It is most disturbing," she said, her voice as frail as moonlight but with all systems go in the brain department. She had never imagined getting old, it was something that happened gradually and one just had to accept it. Often when she looked in the mirror and saw this strange person peering back at her, she wondered at the creature she had become. "You just have to make do with what you've got," another woman said as she circled her Betty Boop mouth with lipstick before hurtling off, as much as one can in advanced years, to another of the village's many dos. For Trixie and Bruce, who were about to tie the knot in their mid-80s, there was plenty to look forward to with all the benefits of hindsight. Trixie had fallen for the fresh green vegetables Bruce grew with great success in the allotment. Their courtship had invigorated the whole town and had been the subject of gossip and speculation at the bowling green. Bowls was the sport of choice for these golden oldies who didn't bother about the rules too much. For Ken and Margaret, who still enjoyed sparring with each other about philosophy and religion, they had done so much time together that, according to Ken, Margaret was part of himself. Margaret, with great candour, said the romance had long left the scene but what was left was bankable companionship. Joanne, the baby of the community in her early 60s, still sporting brunette locks, was even more frank about her misspent youth. In the 1960s she had taken acid and swanned about in fur coats literally tuning in and dropping out, spending time in the bin. A devotee of Bob Dylan, Joanne had recently belted into Wellington to catch the great bard's concert and bumped into some of her now-faded flower child chums and hoped they might soon head up the coast to the retirement village. Patrick, a man of great virility, apparently, even in his 90s, had turned many a head, including Nancy's, who admitted if she had been a little younger might have set her very dignified cap at him. But it was nonsense at this great age, she said with bittersweet acceptance. The trick of growing old, according to Beryl, as she fed her clothes through an old-fashioned wringer, was to concentrate on what you could do rather then dwell miserably on what you couldn't. Geoff wasn't so sure he would chance his arm at an encounter in the boudoir if the occasion might arise, even though he'd managed quite successfully not so long ago. Better to end some areas off on a good note rather than run at the jump and fall, he thought sagely. Of all the documentaries we have seen about ourselves in the Inside New Zealand slot, surely this one contained the most interesting people we have met yet. These were articulate, frank and wise people who had nothing to lose and could talk about their lives, shooting straight from the replaced hip. The talent featured in The Last Resort will make many of us rethink the contribution these experienced hands could make in a society which has been busy putting them in the shadows for the past 20 years. They had joy, they had fun, they had seasons in the sun and gave the adventurers in the highly successful, The Last of the Summer Wine, a run for their money. When we look at the indomitable Nancy, who died a month after filming for this documentary, and all the others who helped to demystify old age, we are looking at ourselves and that is why we have to look. Hopefully we might be able to do as well as these brave and fascinating souls. Source: The Dominion Tuesday 6 April 1999

One More Kiss...

Two-year-old Robert greets his 85-year-old grandfather Christy in Cape Town. Source: Sunday Star-Times 25 March 2001 from "Family", part of the MILK series by Geoff Blackwell

For articles related to ageing, including feats that can be accomplished, and a non-spiritual look at what happens after death - funerals, jerky, popsicles, fertiliser, ashes, orbit or dust - clicking the

"Up" button below takes you to the Index page for this Older and Under section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment

Don't build a glass house if you're worried about saving money on heating.

Don't build a glass house if you're worried about saving money on heating.