Donating Your Body to Science

Death WishDeath is the wish of some, the relief of many, and the end of all. - Lucius Annaeus Seneca

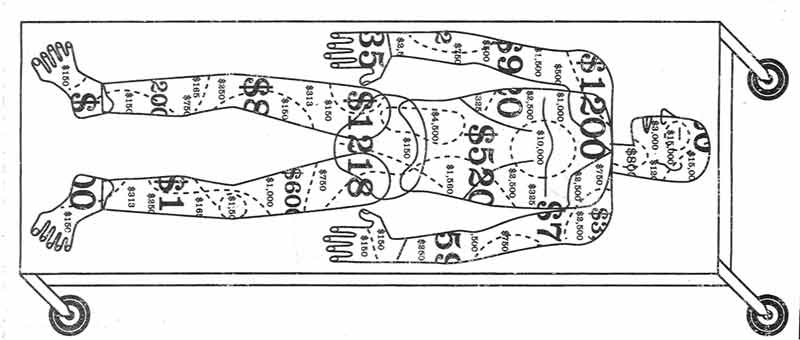

by Mary Roach San Francisco - Because I've written about the cadavers used in medical research, I am frequently asked if I plan to become one. While I haven't yet signed the forms, I find the idea appealing. I'm an altruistic sort, but more than that I'm cheap - and the thousands of dollars in savings on funeral expenses is hard to pass up. What's more, being carved into bits and chunks and shipped to a dozen different universities and institutions seems no more distasteful than decomposing in the dark underground or being burned to char in a crematory retort. I'm all for post-mortem adventure and travel. (I'm told that if you donate your brain to the Harvard Brain Bank, for instance, it rides up front in the cockpit on the plane to Boston.) I'm happy to donate my body to science as long as no one profits from my parts. But this wish is becoming increasingly difficult to safeguard now that body parts are hot property. Just last week, the director of the cadaver research program at the University of California, Los Angeles, was arrested and accused of selling donated body parts to medical researchers elsewhere. This raises the question: is compensation for bodies or their parts such a bad idea? Leaving one's body to science has historically been an act of pure generosity, but if the human tissue shortage is so dire that biotechnology companies and medical researchers are resorting to black market purchases, then maybe the system should be rethought. It's my body, and if anyone is going to make money from it, it should be me or my family. Perhaps a modest financial incentive for donating one's remains to medical research will inspire more people to do it. Bear in mind, this is different from offering money for organs to be used in transplants. Doing that runs the risk that impoverished individuals may be tempted - or pressured - to sell a kidney for cash even if it's dangerous for their health. There's also the possibility that families of brain-dead patients, the source of most organs for transplants, could make decisions that are unduly affected by the prospect of payment. But compensating the future dead, or their families, poses no such risk, although some precautions should be in order, like fingerprinting before and after death to ensure that the dead body in the box was the same as the living body that signed the donor form. But basically, I take a utilitarian stance. I'm not going to be using my body once I'm dead, so if some good can come of parcelling it out for medical research, I'm all for it. And if a reasonable cash outlay is all it takes to get 10,000 or 20,000 Americans over their aesthetic qualms and into my camp, then everybody wins. Everybody except the funeral industry, and it has been winning long enough. Mary Roach is the author of Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers Source: The New York Times Thursday 11 March 2004 illustration by M K Mabry

The Ultimate Donation: How to Give Your Body to Science and Keep It Safeby Tara Parker-Pope What really happens to your body when you donate it to science? Recent reports about bodies being blown up or cut into pieces by chain saws have given us a ghoulish glimpse of what happens to cadavers used in medical research. But far from putting us off the notion of donating our bodies to science, the scandals should serve as powerful reminders of the amazing contributions we can make after we die. The details of cadaver research may make you squeamish, but the results are impressive. Bodies donated to science have helped create crash-test dummies and safer cars, protective gear for soldiers and a better understanding of numerous diseases. While demand for research cadavers remains strong, willed-body programs have come under scrutiny recently. At the University of California, Los Angeles, an employee was accused of selling body parts for research. Bodies donated to Tulane University were used in military studies of protective gear for soldiers who encounter land mines. But what has been lost in the headlines is that while there were certainly ethical lapses and administrative mistakes, all of the bodies were nonetheless used for legitimate medical research. People who are considering donating their body to science generally are advised to contact their nearest university medical school, to make transport of the body easiest. In most cases, the institution promises to use the body for teaching purposes or medical research. But that can include a variety of uses, so potential donors should ask for a detailed explanation of what types of research might be performed. Although the institution typically decides how and where a body is used, sometimes potential donors and family members can specify the ways they don't want the body used or direct the donation to a specific researcher. Many universities bear all the costs associated with body donation, as long as the body is nearby. Other institutions might require family members to arrange for transport. Many cadavers donated to universities are used for medical students, who dissect every inch of the body. Ask what steps are taken to preserve the dignity of the deceased, such as wrapping the body and keeping the head covered. Many schools have their own rituals that students use to show respect, including memorial services and "blessing" ceremonies. "You never forget your cadaver," says Francine Benes, director of the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center at McLean Hospital in Boston who in medical school studied the body of an 87-year-old woman. "It was extraordinary that we had dissected every single muscle, every nerve ... and that we had taken her gift and hopefully used it well to become good doctors." Not every body is left intact. Some bodies, as was the case in the UCLA scandal, are cut into pieces, a practice that allows one body to support a wide range of research. A leg can be sent to an orthopædic researcher, for instance, while a head can be studied by a neurosurgeon. "The vast majority of the public has no sense of the breadth of uses for cadavers," says Mary Roach, author of Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers. "The nitty, gritty reality is the body goes where it's needed, and sometimes that means you have to cut it into pieces. It's part of the respect of the person that you make the most of it." Some research doesn't involve cutting the body, but rather studying how a body endures a car crash or whether safety equipment can protect a body from an explosion or fall. Some bodies donated to Wayne State University in Detroit, for instance, are used in impact tolerance tests to help design crash-test dummies or to assess car safety. As a sign of respect, the heads of the bodies are left covered. "It's not gory," says Albert King, chairman of biomedical engineering. He says at least a dozen lives are saved for every cadaver used in testing. "We're preventing a lot of disabling injuries, head injuries, foot injuries and the suffering that many people go through," he says. Potential donors should also ask what happens to a body if a university doesn't need it, and whether auditing systems are in place to track how the body is used. Donors should ask whether the university itself distributes the bodies to other researchers and institutions or whether they employ a private body broker, which is less accountable to a donor's family. Tulane used a body broker to send surplus cadavers to other medical schools, but several ended up in military medical research. The problem, say experts, isn't the safety research for which the cadavers were used, but the fact that family members may not have been told of the possibility. A university "has a special responsibility to follow all the bodies they're entrusted with and carefully see where they end up," says Michael Meyer, philosophy and medical ethics professor at Santa Clara University. Finally, potential donors and family members should ask what happens to a body when the research is complete. Many medical schools cremate the bodies. Some hold memorial services, and family members may be allowed to attend. A few universities, such as Wayne State, promise to return remains to family members. People who work in willed-body programs say the most important thing is for potential donors or family members to make all of their concerns known. Says Allan Basbaum, anatomy chairman at the University of California, San Francisco, "We go out of our way to emphasise to the family that it's a very special donation." AfterlifeHere's a look at some of the various uses for bodies donated to science. Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, Boston: Brain tissue used for various neurological research. Forensic Anthropology Center, University of Tennessee, Knoxville: The "Body Farm" research aids in crime solving. Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland: Donations teach military doctors and aid military safety research. Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, Albuquerque, New Mexico: Laboratory of Human Osteology collects bones for research; family can visit remains. Source: The Wall Street Journal Tuesday 10 March 2004

A Time to Die - But Please Wait until Januaryby Arven Hann People wanting to donate their bodies to Otago University medical research will have to delay dying until January because the university has no room to store them. The university has placed a moratorium on accepting bodies from Canterbury because it ran out of storage space after a high number of deaths in the past year. The bequest co-ordinator for the anatomy and structural biology department, Kathryn McClea, said the department had imposed the moratorium reluctantly. It was "most grateful to persons who so generously bequeath their bodies for anatomical study. The anatomical examination of a donor's body extends through a teaching year or beyond so that a period of 18 months or longer normally passes between the death of the donor and the final cremation of his or her remains," she said. "With a larger number of deaths this year - and bodies being retained longer for study - we have reached our capacity to store them." One 86-year-old Christchurch resident, who declined to be named, said he was surprised when he received a letter from the university in September saying his body would not be accepted this year. "I wanted to donate my body, and I talked it over with my family and then filled in the forms and was accepted," he said. "I burst out laughing when I read the letter. I guess I will just have to hold on for a while, but at the moment I am expecting to be able to do that." The department receives on average 100 bequest forms a year and about 40 bodies from Otago, Canterbury, Nelson and Marlborough. Source: stuff.co.nz 30 November 2006

Donations of Brains Are Probed in Maineby Stephanie Ebbert and Sean Murphy A Maine special prosecutor is interviewing the families of about 100 people who died suspicious or unexpected deaths to determine whether their brains were improperly removed from their bodies for research. The brains were shipped from the Maine medical examiner's office to a Maryland institute for research, and a state employee collected fees of $1,000 to $2,000 for each one. Some families are saying they never consented to the organ donations, setting off state and federal investigations. The shipments to the Bethesda-based Stanley Medical Research Institute have been halted. "It wasn't an organ donation; it was an organ taking," said lawyer Alison Wholey Mynick. She said her firm plans a lawsuit on behalf of a client who refused a request to donate the brain of a middle-aged spouse but later learned from investigators that the organ had been seized anyway. The probe has ignited concern about tissue donation for research, a field that specialists say is poorly regulated and vulnerable to exploitation. Grieving relatives, contacted by phone in the hours or days after a death, typically have no record of what they agreed to donate, critics say. The organs are coveted by researchers, who sometimes make arrangements with states to seek access to cadavers. From 1999 through spring 2003, the Maine medical examiner's office allowed Stanley Medical Research Institute to collect brains from cadavers, with permission from families. The institute supports research on schizophrenia and manic depression and provides brains to researchers worldwide. Matthew Cyr - the state's funeral inspector, who had a contract answering after-hours calls for the medical examiner's office - earned $1,000 a month for supplying brains to Stanley, plus $1,000 for each normal brain and $2,000 for every brain of a deceased person diagnosed as schizophrenic or manic depressive. After receiving complaints from families, Attorney General Steven Rowe and US Attorney Paula Silsby announced an investigation in November, said Chuck Dow, director of communications and legislative affairs. Recently, Rowe appointed Assistant US Attorney Rick Murphy to serve as special prosecutor and take over the state probe, since Rowe's office oversees that of the medical examiner. "I want to avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest with respect to the investigation and subsequent decision-making regarding this matter," Rowe said in a statement. The probe followed a lawsuit by a Gorham, Maine, couple who said their son's brain was taken without their permission. A settlement was reached through a mediator, but the couple's lawyer, John Campbell, declined to disclose the terms yesterday. When A J Gagnon died of an accidental drug overdose at age 28 in April 2003, his mother, Lorraine Gagnon, agreed to let a small piece of his brain tissue be used for research, Campbell said. She said she soon received a letter from Stanley thanking her for her son's contribution to research on schizophrenia. Lorraine Gagnon contacted the Stanley institute and realised they had taken his entire brain. Campbell said they also took tissue from Gagnon's liver, spleen, and pituitary gland, none of which she had agreed to, Campbell said. Byrne J Decker, a lawyer with the Portland law firm representing Stanley Research, declined comment on behalf of the institute, because of the ongoing investigations. Stanley stopped collecting brains from the Maine medical examiner's office in May 2003. The medical examiner's office is in the process of changing its procedures on organ and tissue donations. Cyr, a police officer in the town of Bucksport is no longer working for the medical examiner. Neither he nor his lawyer could be reached last night. Maine, like many states, allows organs to be harvested from cadavers, provided that a family member gives consent over the phone if the call is recorded or if there is a witness listening on the line. Campbell argues that the system could be vastly improved if written consent is required, which would not only protect relatives against unscrupulous organ harvesters, but it could also protect research organisations against claims by grieving relatives that they did not understand the agreement. But Arthur Caplan, director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania, said that, unlike organ donations for living recipients, donations from cadavers are only loosely regulated. "The only thing that stands between this sample and the grave is someone wanting to study it," said Caplan, author of The Ethics Of Organ Transplants. The Massachusetts Office of the Chief Medical Examiner last year ended its involvement in organ or tissue donation, after the state Ethics Commission found a conflict of interest, said Katie Ford, spokeswoman for the Executive Office of Public Safety, which oversees the office. The commission pointed to the office's reliance on employees of two private organ banks to prepare official case reports on suspicious deaths rather than hiring office staff. It said the organ bank employees had an interest in quickly releasing bodies for organ and tissue donation, while the medical examiner's duty is to painstakingly investigate and determine the cause of death. Source: boston.com 6 January 2005 © Globe Newspaper Company

Okay - this was a joke, but I happen to think it's a decent idea. Just consider that the typical 10-acre cemetery contains enough coffin wood to construct more than 40 houses, 900+ tons of casket steel, and 20,000 tons of vault concrete. To that add a volume of formallin sufficient to fill a small backyard swimming pool and untold gallons of pesticide and weed killer to keep the graveyard unnaturally green Yes Men Crash Oil Expo, Propose Turning Corpses into Fuel

Vivoleum candles supposedly made from a former Exxon janitor who died from cleaning a toxic spill. Master pranksters The Yes Men crashed the Gas and Oil Exposition 2007 in Calgary this week, impersonating a rep from the National Petroleum Council at a keynote in which they proposed to convert people who died from climate change disasters into fuel. After noting that current energy policies will likely lead to "huge global calamities" and disrupt oil supplies, Wolff told the audience "that in the worst case scenario, the oil industry could "keep fuel flowing" by transforming the billions of people who die into oil," said a Yes Men press release. Yes Man Mike Bonnano, posing as an Exxon representative named Florian Osenberg, added that "With more fossil fuels comes a greater chance of disaster, but that means more feedstock for Vivoleum. Fuel will continue to flow for those of us left." The impostors led growingly suspicious attendees in lighting Vivoleum candles made, they said, from a former Exxon janitor who died from cleaning a toxic spill. When shown a mock video of the janitor professing his desire to be turned in death into candles, a conference organiser pulled Bonanno and Bichlbaum from the stage. As security guards led Bonanno from the room, Bichlbaum told reporters that "Without oil we could no longer produce or transport food, and most of humanity would starve. That would be a tragedy, but at least all those bodies could be turned into fuel for the rest of us." Sources: boingboing.net 15 June 2007

The Vivoleum program is not really an initiative of the ExxonMobil corporation - but maybe it should be...

In the actual speech, the "NPC rep" announced that current US and Canadian energy policies (notably the massive, carbon-intensive exploitation of Alberta's oil sands, and the development of liquid coal) are increasing the chances of huge global calamities. But he reassured the audience that in the worst case scenario, the oil industry could "keep fuel flowing" by transforming the billions of people who die into oil. "We need something like whales, but infinitely more abundant," said "NPC rep" "Shepard Wolff" (actually Andy Bichlbaum of the Yes Men), before describing the technology used to render human flesh into a new Exxon oil product called Vivoleum. "We've got to get ready. After all, fossil fuel development like that of my company is increasing the chances of catastrophic climate change, which could lead to massive calamities, causing migration and conflicts that would likely disable the pipelines and oil wells. Without oil we could no longer produce or transport food, and most of humanity would starve. That would be a tragedy, but at least all those bodies could be turned into fuel for the rest of us." "We're not talking about killing anyone," added the supposed NPC representative. "We're talking about using them after nature has done the hard work. After all, 150,000 people already die from climate-change related effects every year. That's only going to go up - maybe way, way up. Will it all go to waste? That would be cruel." Security guards then dragged Bichlbaum away from the reporters, and he and Bonanno were detained until Calgary Police Service officers could arrive. The policemen, determining that no major infractions had been committed, permitted the Yes Men to leave. Canada's oil sands, along with "liquid coal," are keystones of Bush's Energy Security plan. Mining the oil sands is one of the dirtiest forms of oil production and has turned Canada into one of the world's worst carbon emitters. The production of "liquid coal" has twice the carbon footprint as that of ordinary gasoline. Such technologies increase the likelihood of massive climate catastrophes that will condemn to death untold millions of people, mainly poor. "If our idea of energy security is to increase the chances of climate calamity, we have a very funny sense of what security really is," Bonanno said. "While ExxonMobil continues to post record profits, they use their money to persuade governments to do nothing about climate change. This is a crime against humanity." "Putting the former Exxon CEO in charge of the NPC, and soliciting his advice on our energy future, is like putting the wolf in charge of the flock," said "Shepard Wolff" (Bichlbaum). "Exxon has done more damage to the environment and to our chances of survival than any other company on earth. Why should we let them determine our future?" Source: dailykos.com photo source: theyesmen.org See also:

For articles related to ageing, including feats that can be accomplished, and a non-spiritual look at what happens after death - funerals, jerky, popsicles, fertiliser, ashes,

orbit or dust - click the "Up" button below to take you to the Index page for this Older and Under section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment