Eyeballs for Sale

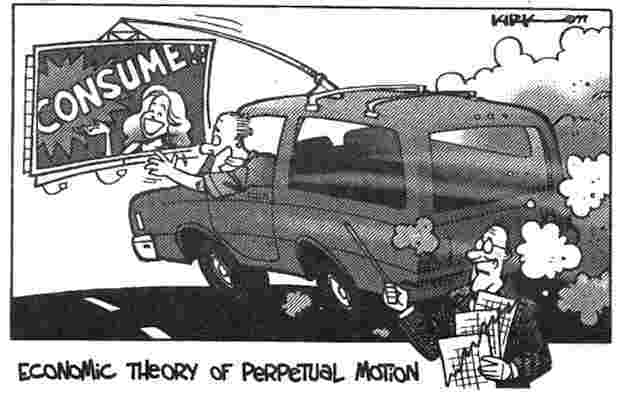

Perpetual MotionThere is nothing so well known as that we should not expect something for nothing - - Edward W Howe Gambling: The sure way of getting nothing for something. - Wilson Mizner In day-to-day commerce, television is not so much interested in the business of communications - Les Brown

Source: Funny Times, May 2000

Perhaps the sign should say "Buy"? Collectors and hoarders have somewhat different objectives than mere consumers.

A piece of the pyramid or a piece of the pie? Something for Nothingby Ted Lewis

According to Schumpeter, capitalism works because the consumer doesn't know what things really cost. But now the Internet lets consumers wield price comparing agents that find the best price for anything. Such perfect pricing information drives all profit from the economic system. It even outpaces cleverness: "Except in rare niches, the Net produces speedy imitation and thin margins," concludes Kuttner, "so it's very difficult even for innovators to make a buck." The Web, then, portends a bleak future for free enterprise. Or does it? Giving Away the Company JewelsFriction-free economy companies may have found a solution to Schumpeter's dilemma. Whether it's a freeware browser, an open source operating system, or a plain old cellular phone, simply give it away. The consumer can exercise perfect information about prices without upsetting the economic order, because everything is free.

Table 1: Strategies of the strong and weak Which companies might actually do this? Table 1 divides businesses into two categories, then lists the strategies that apply to each group. Strong companies have the budgets and market share to do everything. For example, HP, IBM, and Compaq can sell computers with a choice of preinstalled operating systems, because doing so is easier than picking winners and losers. Weak companies have limited budgets and market share, so they must pick a niche and focus on one product or service. Because they must also work cheaper and faster than their monster competitors, they are more likely to opt for an open source or freeware strategy. For strong companies, the bottom line is to ride the wave of popular opinion in several areas. They can afford to hedge all bets. They are not, however, likely to give away the company jewels. In contrast, the weak competitor needs an advantage. In an era of online shopping, where perfect pricing is an everyday occurrence, the best strategy is to offer something for nothing, even when it sacrifices profits. E-commerce companies are using several strategies to profit from something for nothing. Weak companies succeed by becoming strong: They progress from niche-filler to player to dominant force within their industry. The way to achieve a strong position is to use the strategies of the weak. Advertising for DollarsE-commerce companies have borrowed a strategy long used by print magazines like EE Times: Let advertising revenues support profits; the product is nothing more than an attention getter. For example, businesses like Slate magazine are lowering or eliminating their subscription fees to attract new online viewers. Slate's 20,000 subscribers no longer pay $20 a month to read it; now advertisers pay the bills. But to make an impact, Slate needs millions of readers, and it couldn't recruit them as long as it charged a subscription fee. In fact, because online magazines are a dime a dozen, Slate could eventually turn to giving away more than just free editorial to build its readership. Value Chain IntegrationWireless telephone providers have long given away the phone to get you hooked on their cellular service. Nothing is really free, though, because the telephone manufacturer and the service provider are a digital keiretsu, a symbiotic combination of two or more companies, that provides profits for every company linked to the integrated value chain. For example, ISPs, emerging Linux service companies, and OEMs may be coalescing into an integrated value chain. "Our customers [Internet service providers] are looking for an OS that is not as cost-prohibitive as other Unix variants," says Mike Binko of PSINet, an ISP provider that uses Linux. Although offering initially lower costs, such a company looks forward to a steady stream of service and support fees once it hooks an ISP on Linux. OEMs are also interested in Linux as a way of selling more hardware (David Pendery, "HP, Dell, and Compaq Herald Linux Hardware, Service Plans," Info World Electric, 29 Jan 1999 www.infoworld.com). Sticky BusinessesTypically, Netheads skip all over the Net. They ignore most banner ads and spend less time at anyone Web site as the overall number of sites grows. As a result, "network stickiness" - the length of time the average Nethead spends viewing a site - now counts more than hit rate. According to reporter George Anders ("The Race for Sticky Web Sites," The Wall Street Journal 11 Feb 1999 p. B1), AOL and gamesville.com lead the pack with an average consumer stickiness of 246 minutes per month. Yahoo.com averages 60 minutes, and Etrade.com, 37 minutes. These "sticky businesses" have a high percentage of repeat customers loyal to the store, product, or Web site. Freebies can make a business sticky. Think about how grocery stores use loss leaders to get you into the store and a reward card to bring you back. Similarly, software developers trade short-term giveaways for long-term business: Once they get you hooked into a particular software package, they charge for upgrades or add-on services. New StrategiesThe latest crop of e-commerce upstarts are taking something-for-nothing strategies to new heights and in new directions. They appear to be defying economic gravity by giving away millions of dollars in merchandise without any prospect of profiting by selling a product. For example, more than 600,000 consumers rushed to claim one of Free-PC.com's 10,000 Compaq PCs, valued at $600 each. NetZero.net gained 350,000 customers in just 3 months by giving away free Internet access. According to San Jose Mercury News staff writer Deborah Kong, it took Maryland-based Broadpoint.com less than a month to snag 115,000 subscribers with its free long-distance telephone service ("En Garde Online," 13 Feb 1999 p. 1A). Buy.com sells books, CDs, and computer gear below cost. How do such companies hope to make a profit? These latest something-for-nothing strategies are more sinister than past giveaway gimmicks because they put a bounty on your attention span, which could eventually lead to e-commerce businesses packaging and selling your most private thoughts. To get "free" goodies, consumers may ultimately surrender their privacy. A Bounty on EyeballsMajor companies have already begun to put a price on the head of every e-commerce consumer: Microsoft paid $35 per subscriber when it bought Hotmail.com, while America Online paid $100 per Netscape customer. This trend results directly from the advertising-revenue model that currently dominates e-commerce. Consumers are called "eyeballs" because attracting your visual attention is the main force driving e-businesses. Such businesses need not profit from product sales if they can attract lots of attention. When valued at $35 to $100 per eyeball, a Web site that sells products at a loss is still worth billions. Attention capturing may well be the strategy of companies like Buy.com and Free-PC.com. Because they can sellout to a larger competitor for $100 per customer, it isn't necessary to make a profit - ever. Capture lots of eyeballs by giving consumers something for nothing, sellout, move on to the next initial public offering, and leave stockholders holding the (empty) bag. This strategy may explain why Yahoo paid $3 billion for GeoCities.com, and Excite.com fetched $6 billion from @Home. Invasion of the Mind SnatchersHowever, there are already signs that the "eyeballs-for-bucks" game is nearing the end of its effectiveness, as consumers grow weary of banner ads. To keep their customers coming back, e-commerce retailers must resort to more sophisticated techniques. In fact, e-commerce sites have begun to use methods that make novelist George Orwell's Big Brother seem like Disney.com. What these sites do is entice consumers to surrender their privacy for a surprisingly low price. The consumer gets a free PC or a few hours of online access in exchange for revealing his or her deepest secrets. The electronic mining of private information has begun. Free-PC.com, for example, asks several questions before it doles out a PC. To qualify, customers must reveal the gender and age of every household member, as well as the types of consumer electronic devices each owns. To keep the PC, the customer must promise to spend at least 10 hours watching two gigabytes of ads preloaded onto the new PC. Users cannot block or remove any ad that appears on their screen while cruising the Web. Free-PC.com tracks online user behaviour so that it can follow up with targeted promotions. Something for nothing works in favour of the seller, because a buyer's psychological profile is even more valuable than a potential buyer's attention. These strategies take their cue from reward cards, which exchange grocery discounts for comprehensively tracking everything you buy. But Web-based strategies crank up the tracking by an order of magnitude, as only computer technology can. Imagine what marketing people will do with a minute-by-minute trace of consumers' Web surfing habits. Where will something-for-nothing strategies lead? Psychologist Abraham Maslow's work provides a clue. More than 30 years ago he classified human needs according to a hierarchy that scales from the most basic to the most sublime. At the bottom of Maslow's ladder are physical needs, such as food and water; most Netheads already have enough to eat. Next is the need to feel safe. Again, Netheads are well off enough to feel secure - at least while they're online. Maslow's next three levels address our needs for social acceptance, self-esteem, and self-actualisation. These last levels are where selling over the Internet comes in. By appealing to the social animal, for example, America Online has created one of the stickiest Web sites in cyberspace. AOL's online chat rooms provide a value that keeps customers coming back. Similarly, e-commerce sites that appeal to the ego - the yearning to know, to be competent, and to gain respect rapidly build communities of loyal consumers, as the women-oriented iVillage.com has done, for example. Crowning Maslow's hierarchy is the need for self-actualisation: finding your life's work and purpose. So far, despite sprawling job sites like CareerMosaic, this is an untapped market-but one that, if mined successfully, will prove to be the next big thing on the Web. For now, however, the something-for-nothing deal will continue to prove a Faustian bargain. Consumers will fall over each other to give away their privacy or lock themselves into a certain product or service. And because the friction-free economy makes it all so easy, it will happen in Internet Time. Ted Lewis is the author of The Friction-Free Economy (HarperCollins, 1997), and co-author with Hesham El-Rewini of Distributed and Parallel Computing (Prentice Hall, 1998). Technology Assessment Group, 13260 Corte Lindo, Salinas, CA 93908; tedglewis@friction-free-economy.com Source: IEEE Computer May 1999

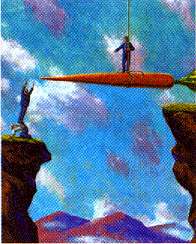

The illustration at the beginning of this article is a curious one. I can't help but wonder what the rope is tied to on the other end...

Our Money, OurselvesWomen should smarten up on gifting clubs. The latest pyramid schemes to come to town are gift-wrapped for women. They look and sound nicer than many such schemes, but they are every bit as bad. Variously called "Women Helping Women," "Women Empowering Women" and "Circle of Friends," proponents say these are "gifting clubs." Defenders say they are legal because the money given is called a "gift" rather than an investment. The California attorney general doesn't agree, and he has lots of company, including police in Sacramento and Placer counties. These schemes, in which bad math and wishful thinking triumph over common sense, are nothing new. They're probably as old as the pyramids and human mischief itself, and they're certainly as American as apple pie and bunco. Men fall for them, too, although the ones they join aren't dressed up as nicely as the gifting clubs for gals. These are cloaked in good intentions and sisterly good will. On occasion, some of the money raised is donated to charity. And it's easy to figure all is on the up and up when a candidate for the job of upholding the law shows up at one. Erik Schlueter, candidate for El Dorado County district attorney, acknowledged he solicited campaign contributions at a Women Helping Women gathering in Folsom. He said he believes the clubs are not prosecutable under state law, a description that falls short of approval and makes one wonder if Schlueter's behaviour falls a bit short of proper. (His actions are being scrutinized by legal authorities.) Some defenders of these gifting clubs say any criticism is just a sexist attempt to thwart women trying to help their own - but empowerment shouldn't carry a price tag. Most galling of all, these clubs rely on participants being mathphobic, falling in line with the tired old stereotype of ditzy females. Talk about sexist! It's great that law enforcement is investigating these clubs, but women should liberate themselves as well with a little clear-thinking computation. In a Women Helping Women club, a woman joins at the bottom or "appetizer plate" level by giving $5,000. There are eight people at the lowest level and their gift is paid altogether - a total of $40,000 - to the lucky "birthday girl" at the top of the pyramid. Before the newcomer can reach that winning "dessert" level, she must make it through the "soup and salad" level of four people, and the "entree level" of two people. Once the "birthday girl" is "gifted" (or paid off), the pyramid splits into two, which means 8 new suckers must join each new pyramid for the progression to continue. Because each payout triggers a split, the numbers of new recruits needed to keep going multiplies faster than crumbs under the party table. The members below the birthday girl in the original pyramid must recruit 112 others in order for all of them to reach the top spot; those 112 in turn must recruit 1,568. The 1,568 must recruit 21,952 others. Pretty soon, everyone has run out of friends and relatives to invite (or hustle, if you prefer), and the pyramid collapses. Math, like sisterhood, is powerful. The law needs to be powerful, too, in shutting down these scams. Source: sacbee.com © The Sacramento Bee "Life Captured Daily" Thursday 19 September 2002

For more articles relating to Money, Politics and Law including globalisation, tax avoidance, consumerism, credit cards, spending, contracts, trust, stocks, fraud, eugenics and

more click the "Up" button below to take you to the Table of Contents for this section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment

In a recent

Business Week article ("The Net: A Market Too Perfect for Profits," 11 May 1998, p. 20), Robert Kuttner argued that the Internet

will topple capitalism by giving consumers too much power. Kuttner quoted mid-century economist Joseph Schumpeter's observation

that "every grocer, every filling station, every manufacturer of gloves or handsaws depends on a degree of market power to assure

profits - a miniature monopoly ...historically, those mini-monopolies have depended on imperfect consumer information."

In a recent

Business Week article ("The Net: A Market Too Perfect for Profits," 11 May 1998, p. 20), Robert Kuttner argued that the Internet

will topple capitalism by giving consumers too much power. Kuttner quoted mid-century economist Joseph Schumpeter's observation

that "every grocer, every filling station, every manufacturer of gloves or handsaws depends on a degree of market power to assure

profits - a miniature monopoly ...historically, those mini-monopolies have depended on imperfect consumer information."