The "Fun" in Dysfunctional

The Nervous Parent's Guide to Online MusicA computer lets you make more mistakes faster than any invention in human history - - Mitch Ratcliffe by Sam Diaz Parents of teenagers and pre-teens may have felt a chill last week as the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) sued 261 people for sharing copyrighted music over the Internet. Suddenly, reassurances from sons and daughters that everything was fine didn't seem so, well, reassuring. We talked to the RIAA, legal experts and industry analysts who've watched this phenomenon of online music sharing rise from the underground days of Napster, and have compiled answers to some of the most frequently asked questions. Q I wasn't sued but am afraid lawyers will come knocking on my door. Is the music industry done filing suits? How can I find out if the

RIAA is coming after me next? Q I heard about this Clean Slate amnesty program as a way of keeping my name off the RIAA's lawsuit list. Should I sign it? Q I've heard of KaZaA, Grokster, Morpheus and others. How do these file-sharing programmes work? Q My teenagers say they're not sharing music, just downloading. Does that mean I can breathe easy? Q I told my son to quit downloading music, but he said it's not illegal. Is that correct? Q We paid a fee when we signed up for our peer-to-peer network. Does that mean we're paying for the music? Q Is it legal to have the software on my computer or do I need to uninstall it? Q Do I need to delete the music files I've already downloaded? Q So if I choose to not delete those files, will anyone know it - other than me and my conscience? Q What's the worst thing that can happen if I'm sued for sharing music? Can I go to jail? Q Why don't they just sue KaZaA, Grokster and the others for making the software that allows this to happen? Isn't that how they shut down

Napster? Contact Sam Diaz at sdiaz@mercurynews.com Source: bayarea.com Mercury News Thursday 18 September 2003

What Would Woody Guthrie Do?What would Woody do? Jesse Walker (Reason) suggests that Woody wasn't that big on private property. Creative Commons also reports the following, though I haven't checked the facts myself:

Source: volokh.com Eugene Volokh 29 July 2004

Movie Industry Frowns on Professor's Software Galleryby David F Gallagher

Last month, Professor Touretzky received an e-mail message from the anti-piracy division of the Motion Picture Association of America, the trade group representing major studios, referring to "unauthorised distribution of copyrighted motion pictures" on the site. "We have notified your ISP of the unlawful nature of this Web site and have asked for its immediate removal," the message stated. Professor Touretzky defends the project (cs.cmu.edu), which features submissions from like-minded programmers and academics, saying it grew out of his long-standing interest in free-speech issues. "It never occurred to me that someone would actually try to prevent people from publishing code that they wrote," he said. "The idea just struck me as so deeply offensive that I felt I had to do something about it." The code in question was written in 1999 by programmers who wanted to watch their DVDs on computers running the Linux operating system. No legitimate software for doing this existed at the time. Not to be deterred, the programmers found that the encryption scheme protecting the discs was easy to crack, and in the spirit of the open-source software movement, they distributed their new code to others via the Internet. While Linux users might have rejoiced, the developers of this new so-called DeCSS software ran afoul of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, a controversial federal law passed in 1998 that makes it illegal to offer a way to gain unauthorised access to a copyrighted work protected by encryption. In a widely followed case last summer, the movie industry sued Emmanuel Goldstein, the publisher of 2600, a print and Web publication for hackers, in an effort to stop him from posting the software on his site or linking to it on other sites. the judge sided with the studios, saying that the software was an "epidemic" that could destroy the market for home video. Professor Touretzky testified at the trial after bringing his Web site to the attention of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which paid for Goldstein's defense. To make his point about free speech, he offered several exhibits from his gallery, including a description of the DeCSS code in plain English and a T-shirt on which the code was printed - both of which could be considered illegal under the copyright act. "What I wanted to do was demonstrate that there is no way to draw a line between computer code and other forms of speech that everybody recognises as protected speech," Professor Touretzky said. "I don't think code should be treated any differently than a recipe or an instruction manual." He believes that the judge agreed with him, but that the movie industry still won the case because the judge "invented a new category of speech that was not protected, which basically comes down to anything that threatens the profits" of the studios. The judge's decision has been appealed, and hearings are scheduled to start May 1. Professor Touretzky said that given his involvement with the DeCSS case, the form letter he received last month from the MPAA about his site was probably a mistake. It did, however, provide "an opportunity to embarrass them," he said. In his response to the MPAA, Professor Touretzky asked it to specify which of the several dozen forms of the software on the site it objected to, and to provide a legal basis for that objection. He also noted that the site was by now a "well-known academic work," and asked whether the movie industry was seeking to "exert editorial control over scholarly publications by computer science faculty that deal with DeCSS." Earlier this month the MPAA acknowledged Professor Touretzky's response and said it would "consider it and respond appropriately at the proper time." This does not mean that Professor Touretzky is off the hook. Mark Litvack, vice president and legal director for anti-piracy at the MPAA, questioned whether there was a legal difference between posting the software for academic purposes and posting it to allow others to copy DVDs. "When you post it for the world to see and for the world to take, you can't control how it's used," he said. Litvack noted that a professor who posted child pornography in the context of a class on policing Internet crime would still be breaking the law. "You're not allowed to traffic in it, period," he said. "It's illegal material." But Litvack said the MPAA would not necessarily be concerned about some of the exhibits in Professor Touretzky's gallery, like the T-shirt or the recording of someone singing the computer code with a guitar accompaniment, because these are not "circumvention devices" as defined by the law. "What the MPAA is concerned with is that there are devices that are used to decrypt our movies," he said. "Your T-shirt cannot do that. It's not a device that, by itself, does anything." So what representations of the DeCSS code would upset the MPAA? Litvack said that the question of where to draw the line is "something we will look at and the courts will look at." Meanwhile the gallery continues to grow. Programmers have been competing to come up with the shortest possible code for descrambling DVD encryption. The record-holder is now just 434 bytes long, small enough to fit on a business card. And this month a programmer in Finland with a penchant for math came up with a way to hide the DeCSS code in the digits of a very long prime number, making it perhaps the first such number that is illegal. Watching or copying a DVD using the code on the gallery site would require a fair amount of technical knowledge. But Professor Touretzky said he had heard of new software that makes it easy for anyone to turn a DVD movie into a file on a hard disk, similar to the way CDs can be "ripped" to make MP3 files. He said he would probably not post such software on his site. "I'm more interested in the speech issues than in pirating DVDs," Professor Touretzky said. Even though such software would still be a form of speech, he said, "I'm also really interested in not getting sued. If they're going to sue me, I'm going to make it hard for them." Source: The New York Times from Cyber Law Journal 30 March 30 2001

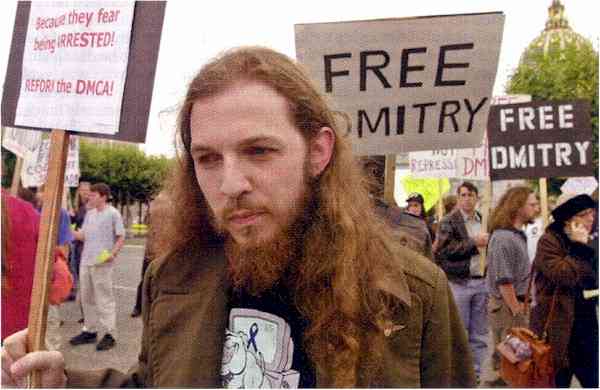

Copyright Law: But Dmitry Did No Wrong

Dmitry's army on the march Beards drooping in the summer fog, 150 computer programmers took to the streets in San Francisco on 30 July to make a protest outside the federal court building. They were rallying in "support of Dmitry Sklyarov, a Russian programmer arrested by the FBI on 16 July after he delivered a paper at a computer conference in Las Vegas. Mr Sklyarov was arrested under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), a 1998 law which bans technologies designed to defeat software that protects copyrighted material. Mr Sklyarov, working in Russia, where, as in most countries, such things are not illegal, had written a program that circumvented some of the limits on eBook Reader, a piece of software for reading text aloud made by Adobe Systems, a Silicon Valley firm. His talk in Las Vegas was about the weaknesses in Adobe's software that made such tricks possible. Mr Sklyarov did not himself make or distribute any illegal copies of electronic books, the kind of activity forbidden by copyright law; nor did ElcomSoft, the firm he worked for. But the DMCA makes it a crime merely to create the tools that can violate copyright - even if those tools have other, legitimate uses (such as the making of a copy of a book by its owner for his own "fair use"). Since Adobe in America was able to buy a copy of the program from ElcomSoft over the Internet, it could argue that the software came under American law, and keep an eye out for the arrival of Mr Sklyarov on American shores. Programmers have been getting steadily more angry at the deadening effect of the DMCA on academic discussions of encryption and research into computer security. Edward Felten, a computer scientist at Princeton, withdrew a paper on weaknesses in encryption systems for digital music after lawyers for the Recording Industry Association of America sent him a warning letter. Mr Felten has challenged the constitutionality of the DMCA with a lawsuit that will be heard later this year. Also working its way through the courts is an appeal against a judgment in favour of the Motion Picture Association of America that 2600, a journal for hackers, could not publish code that allows people to break the encryption systems of digital video discs. Mr Sklyarov's arrest proved a flashpoint, and it set off such a storm of protest that a week later Adobe changed its mind and called on the FBI to release him. Firms may be more susceptible to such public pressure than the government. The federal attorney's office has said that it intends to pursue the prosecution, and support for the DMCA is strong in Congress, where the entertainment industry has lobbied hard. Predictably, at freesklyarov.org, the schedule for more protests is getting longer. And rightly so. Source: The Economist 4 August 2001

After Sklyarov was arrested he was held briefly in a local jail in Las Vegas; then he was held in the Oklahoma City Federal Prisoner Transfer Center until 3 August 2001, when he was transferred to the Federal building in San Jose, California. On 6 August 2001, Sklyarov was released on a US$50,000 bail and was not allowed to leave Northern California. The charges against Sklyarov were later dropped in exchange for his testimony. He was allowed to return to Russia on 13 December 2001. Sklyarov is married with two children. Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmitry_Sklyarov

For IT-related articles on snooping, usage, the future, e-diaries, piracy, flickers, cyborgs, browsing, trends, jokes, philosophic agents, artificial consciousness and more, press the "Up" button

below to take you to the Index page for this Information and Technology section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment Professor David S Touretzky, a computer scientist at Carnegie-Mellon University, says he

has never watched a movie on DVD, much less copied one illegally. So why is the movie industry calling him a pirate? The answer can be found on a university site which houses an unusual

web project launched by Professor Touretzky - a project which has turned him into something of a celebrity in

Internet legal circles. His site is a gallery devoted to representations of a piece of software that has been deemed illegal because it can be used to break through the

copy-protection system on DVD movies.

Professor David S Touretzky, a computer scientist at Carnegie-Mellon University, says he

has never watched a movie on DVD, much less copied one illegally. So why is the movie industry calling him a pirate? The answer can be found on a university site which houses an unusual

web project launched by Professor Touretzky - a project which has turned him into something of a celebrity in

Internet legal circles. His site is a gallery devoted to representations of a piece of software that has been deemed illegal because it can be used to break through the

copy-protection system on DVD movies.