Survivor: The New Economy

Reality TV Drawn from Silicon ValleyIt's better to think about Silicon Valley as a region, rather than as independent firms. - Anna Lee Saxenian by Matt Richtel

Reality-based television shows are heavy with sexual themes and romance, with the action often set against exotic backdrops. It's captivating stuff, no doubt, but the formula is growing a bit tired. In order for reality TV to thrive, it needs new material, inspired by action found closer to home, and in a world filled with the elements of great television - big money, power struggles and heated intellectual property disputes. Yes, this is reality TV drawn from Silicon Valley. Real shows about real people, all watching their stocks tank. The lineup might look something like this:

Matt Richtel reports on technology; his column about living and working in the technology maelstrom, Backslash. appears the second Sunday of each month. E-mail him at mrichtel@nytimes.com Source: The New York Times Sunday 13 May 2001

Reality Television[Excerpt] There are several reasons that reality television has become popular today. The three that I will focus on are the concepts of money, instant fame, and the guilty pleasure phenomenon. The first catalyst for reality television being popular today is money. Today’s shows offer huge sums of money to people who do not necessarily possess the career skills that would make them a productive enough member of society to amass such wealth through honest work. Simplified, dumb people get lots of cash. Now, some shows do in fact have, at least at first, a pseudo-intellectual premise. Who Wants to Be A Millionaire, for example, offered up to a million dollars to people answering a set of questions. The questions, however, differed from related shows in that they were usually trivia oriented. Also, the audience was involved, as well as calling a friend and so on, which added to the drama aspect. The lighting, music, and editing all were contrived to produce the maximum possible suspense surrounding rather innocuous pop culture subjects one might find in any game of Trivial Pursuit for Children. The promise of money and the vicarious joy at someone winning lots of money, or more commonly spectacularly losing said money, is what draws millions of viewers. The second reason I believe reality television has become popular today is that of instant fame. Reality television takes ordinary people, sets them up in extraordinary situations on a world stage with other similarly commonplace individuals, and makes them the focus of a nation’s attention on, for example, an hour every Tuesday. Obviously the majority of the population has no chance of ever being picked as a participant for the show itself, but again the concept of vicarious living kicks in and the audience is hooked. The members of the show are satisfactorily every-day individuals for fans to willfully suspend their disbelief. That’s what keeps 35,000 20-year-olds auditioning every year for a chance to participate in MTV’s The Real World, which offers no monetary reward save the endorsements from being an instant celebrity. The third reason that reality television is popular today is what I like to call guilty pleasure syndrome. Sociology professor Mark Fishman of Brooklyn College, The City University of New York, has made a study of reality TV. "The Germans have a word for it, the appeal of some of these shows," he says. "It's called 'schadenfreude.' It means taking delight in the misfortunes of others. It's a guilty pleasure. You feel you shouldn't be watching. It's always been in good taste not to look at these things. It's a moral envelope that's being pushed. We seem to be in a new age of making public what [we used to think] shouldn't be seen." In today’s society, with the massive technological revolution of home computing and the internet, and with the renewed interest in free speech and the protection of the arts, more and more people are finding premises entertaining that 30 years ago would have been considered obscene. At this point I think it is important to reflect on what these reasons import for society as a whole. The existence of these justifications in and of themselves infers several valid assumptions about American culture, some less than pleasant. The money impetus, or the dollar dilemma, as I call it, is pretty obvious; Americans have become even more infatuated with the concept of personal wealth and personal property. We have become a money-loving society, a society that has taken the inherently good concept of laissez-faire economy and extrapolated it to its logical yet fallible extreme, that of total marketing-based consumerism. We care about what we can buy, what we can buy it with, and how fast we can get it. We indebt ourselves purchasing cars we cannot afford on credit we don’t deserve for applications that don’t require our excessive purchase. We super-size everything, from sport utility vehicles and fast food meals to football games and government bureaucracy. This is a dangerous cultural mindset for a society supposedly founded on the dual ideals of piousness and simplicity. While it may retain us the big kid on the block global police station economic powerhouse position we possess presently, in the long run it ensures avarice and corruption that will not fail to sabotage our economy. The corporate scandals that are just recently being unmasked are the harbingers of a dangerous trend. Our bear market, recessing due largely to lack of consumer faith in the market and government and more in personal property, is an omen of ill-portent. The lack of faith in the market and government leads me to my next assumption concerning the instant fame catalyst. The reason that ordinary people are becoming celebrities has a fairly simple yet disturbing root; the complete vacuum where our store of heroes and idols should be. Our president tells the people what they want to hear. He entertains with rhetoric such as "axis of evil" and "the evil ones". It is not just government that bears the onus of blame. Hollywood is similarly discouraging. From drug arrests for our most talented singers, to child molestation charges and assault arrests, it is a sad day when we have someone like anti-homosexuality aphorism spewing Eminem raising our youth. Until we have real heroes to look up to, society has decided to manufacture its own. The guilty pleasure inference is mostly self-explanatory. While I do believe in the sanctity of free speech, in today’s society more and more people seem to be exercising what I call the assumed right to free noise. As opposed to free speech, which seeks to actually make a comment about something, or contribute a thought worth considering regardless of personal beliefs, free noisemakers intend to sensationalize and shock behind a façade of pretentious "art" mystique they mistakenly believe lends them an automatic air of credibility. We as a society cannot continue to value entertainment which purposefully seeks to not inform. The purpose of mass communication must shift to be one of entertainment coupled with enlightenment; else, we are headed for an ignorant renaissance in which ratings and advertising are the only currency. In conclusion, I will say that the concept of reality television has several distinct flaws, both in its conception and popularity and in what it entails for our attitudes in society as a whole. Until we address these problems, I for one will discourage everyone I know to avoid the latest episode of Survivor or The Bachelor, and hand them a book. Source: zonalatina.com

Coming Soon ... More Reality TV

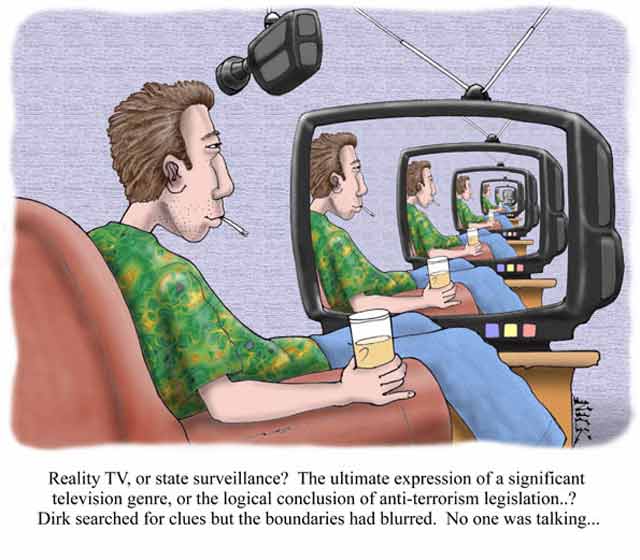

[Excerpt] According to Marshall Allan in his article, "The Case against Voyeur TV," reality TV is full of warped images and sensationalism since viewers watch each character at the worst moments and make unfair, negative judgments. "Part of the appeal of Voyeur TV is that viewers are the ones who 'get it' while watching characters who so obviously don't," Allan said. "We relish seeing ourselves as superior to the people we watch on TV. Herein lies the problem, because easily passed judgments handicap our willingness to relate to people on Voyeur TV and disable our empathy and compassion," Allan added. "The coarsening of individuals polarizes people and has a negative effect on society." [emphasis added] Source: media.www.alestlelive.com (see page 2)

Source: tvscoop.tv

For IT-related articles on snooping, usage, the future, e-diaries, piracy, flickers, cyborgs, browsing, trends, jokes, philosophic agents, artificial consciousness and more, press

the "Up" button below to take you to the Table of Contents for this Information and Technology section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment