P T Barnum & Aristotle?!?

Reality Is So Passé: The "Flattered Self" Is ChicIf some unemployed punk in New Jersey, can get a cassette to make love to Elle McPherson for $19.95, -Dennis Miller

by Jonathon Keats Review of the book Mediated by Thomas de Zengotita Seeking to interest visitors in George Washington's life, curators at his Mount Vernon estate recently attempted to recreate the deathbed stench of the first president as he lay in state. They gave up on the idea, but their instinct was perfectly in sync with a culture consumed by 24-hour technicolor surround-sound entertainment. "Real isn't real enough," writes Thomas de Zengotita in Mediated, his spectacular widescreen critique of contemporary American culture. "That's the telltale sign of an otherwise invisible tipping point in the historical balance between representation and represented. It marks a threshold of saturation, the point beyond which no real entity can survive in popular culture." George Washington's sad fate runs deeper than the common complaint that we live in an age without heroes. Indeed, the reason his story no longer looms as large as Mount Rushmore helps explain how our world came to be mediated, and what it means to live in it. Compare Washington for a moment with those who now command widespread public enthusiasm, people such as Eminem, Oprah, and Barry Bonds. What distinguishes them is that they're here to perform for us. That's their foremost talent. They're consumer goods, glibly packaged products. Their images can be mixed and matched, ours for the taking, as disposable as press-on nails. The defining feature of our culture, according to de Zengotita, is our mass narcissism. He refers to this as the "flattered self, a self that exists in its very own field of representations, that constructs its own identity, chooses what it wants to be." We got to be that way primarily because of the astonishing abundance of opportunities that have practically defined the 20th century, perhaps best illustrated by the fact that, in a single afternoon, the average American is exposed to more vibrant sensations in greater variety than was Constantine or Henry VIII or Napoleon over a whole lifetime. "Reality is becoming indistinguishable from representation in a qualitatively new way," de Zengotita claims. Reality tv and blogging, for example, conveniently close the loop on our narcissism, eliminating the middleman. Prenups and iPods represent the apotheosis of optionality in our lives. Whereas marriage was once forever and music was a special occasion, our experience of reality is now malleable, a customised environment, a virtual extension of our desires. And both of these strands tie together in our fascination with cloning - what could be more narcissistic than living among optional selves? De Zengotita's book may be just the "real entity" to make us flinch - and think. Jonathon Keats is a freelance writer in San Francisco. Source: csmonitor.com 8 March 2005

Amazon Reviewby M Jeffrey McMahon In Mediated (at one time titled The Flattered Self), de Zengotita shows how a media-saturated culture has created a new breed of narcissists - namely you and me. We are, de Zengotita argues, so self-absorbed, so obsessed with our own flattery, so hell-bent on the creation of our own perverse sense of celebrity that we have lost the true measure of greatness. For example, he argues that we can no longer aspire to great heroism because truly heroic figures are no longer relevant in our media world. Heroism, which requires devotion, sacrifice, imagination, and mythos, has been replaced with counterfeit celebrity that makes "heroism" appealing only when it's a consumer product. Literalism, self-aggrandizement, being pandered to by an onslaught of advertisers in every media form, and the resulting delusion that we are always the centre of the universe makes us into pseudo celebrities so that we have no room in our consciousness for the real heroes of the world. He makes a great case for the fact that we have become, thanks to the media, more like full-time actors than real humans. All of us, he says, have learned from television "method acting," so that a media person could stick a microphone in front of any Average Joe and that Average Joe would be able to give a polished interview. We're all competing to be the star in a world of wannabe celebrities. He does a good job of showing how television gives us a God's-eye view of everything so that we have a delusion of omniscience and this false power fuels our delusions of grandeur. Additionally, this God's-eye view spoils us so that we can't live in stillness and see life in the here and now but only media's cheap, hyped representations of life. This unhealthy quest for god-hood, he shows, has taken shape in the popularity of reality tv shows, which feed our sense of entitlement, self-pity, and our narcissistic wish to be recognised over others. By showing how our inability to embrace true heroes connects to our obsession with making ourselves into pseudo heroes, de Zengotita has found an original, sometimes funny, and always profound way to make us look at the way the media is shaping our psyches and our souls. Source: amazon.com 21 November 2004

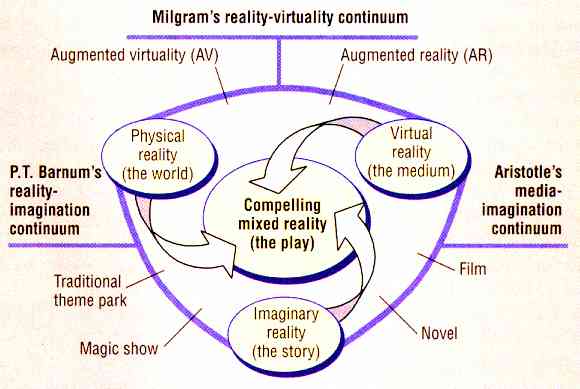

Applying Mixed Reality to Entertainmentby Christopher Stapleton, Charles Hughes, Michael Moshell, Paulius Micikevicius and Marty Altman The lack of compelling content has relegated many promising entertainment technologies to laboratory curiosities. Although mixed-reality techniques show great potential, the entertainment business is not about technology. To penetrate these huge markets, MR technology must become transparent for the content to have full effect. To achieve this goal, we have devised a framework that lets us integrate concepts from disparate areas such as theme parks, theatre, and film into a comprehensive research methodology. We believe that our framework, which has already helped us create content for MR entertainment systems, can provide these benefits to other developers as well. Mixed-Reality ContinuumFantasy and reality meet effectively in film-based thrill rides such as those seen at Universal Studios and similar attractions. The art of mixing reality and fantasy through technology began long before Ivan Sutherland's Sketchpad gave birth to virtual and augmented reality in the 1960s. This was demonstrated in the first hybrid ride-and-film attraction, the Cinerama Air-Balloon Panorama, which appeared more than a century ago in Paris (Walt Brandsford, "The Past Is No Illusion," Digital Illusion, Entertaining the Future with High Technology, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts, 1997, pages 49 - 57). When devising such effects, inventors often undervalue artistic convention and methodology. Their focus on technology sometimes gives them tunnel vision so severe they see only a fraction of the possibilities. Critical technical advancements such as video see-through headsets can provide artists with the means to apply more than 100 years of media conventions to augmented-reality projects. This technology lets them build fantasies that go beyond the simple overlay of texts and graphics in space. Paul Milgram first introduced the concept of mixed reality as a spectrum that extends from real to virtual experiences, with augmented reality and augmented virtuality bridging the two (Paul Milgram et al, "Augmented Reality: A Class of Displays on the Reality-Virtuality Continuum," Proceedings of SPIE: Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies, volume 2351, Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers, Bellingham, Washington, 1994, pages 282 - 292). We expand this continuum by incorporating the mixed-reality participant's imagination to the framework. Mixed-Fantasy Framework

Figure 1. Mixed-fantasy framework. Building on Milgram's continuum, which spans augmented and virtual reality, To map our mixed-fantasy framework, we constructed the three-sided diagram shown in Figure 1. Using Milgram's spectrum as the top edge, we added two new facets: P T Barnum's reality-imagination continuum on the left and Aristotle's media-imagination continuum on the right. We then made imagination the framework's third anchor point. We can locate many media phenomena along the continuum edges, with the ultimate sweet spot for mixed-reality entertainment applications - mixed fantasy - lying in the centre of these phenomena. A successful mixed fantasy should thus incorporate strong doses of physical reality with virtual elements that lead the imagination, and it should underpin these elements with a central story built on the converging media's artistic conventions. To develop a framework for understanding how to tell stories and entertain people in mixed-reality environments, we draw upon continuums demonstrated by P T Barnum and Aristotle. Connecting reality and imaginationP T Barnum exemplifies modern showmanship. He knew how to structure people's expectations and excite their imaginations so that they would perceive ordinary objects in extraordinary ways - and willingly pay for the privilege. People's desire to believe is so great, this type of magician can transform the perception of reality to his will by painting with the audience's generous imagination. The theme park design industry is today's principal reservoir of this skill for bending the audience's perception of reality. Its methods, while taught in very few academic curricula, are critical. Connecting media and imaginationAfter the spoken word, the stage provided the first entertainment medium, one populated by costumed actors representing imaginary characters. Aristotle's Poetics sought to structure these experiences by using the author's intent to excite the audience's imagination, encouraging them to creatively supply the story's unseen parts. From this basis grew today's theatrical, film, and television industries. As Aristotle pointed out when differentiating the historian from the poet, "it is not the function of the poet to relate what has happened, but what may happen." The storyteller uses this what-if factor to spark the audience's imagination into providing a fantastical reality - a truth that led Ernest Hemingway to observe that the majority of any story exists "beyond the page," and depends on contributions from the reader's imagination. Barnum versus ArlstotieOf these two approaches, Barnum's places users in the more active role, while Aristotle's stresses passive participation. Yet both approaches can be used to construct fantasy

worlds in which the user validates fantasy with reality through imagination and suspension of disbelief. Building Mixed FantasiesTheatrical design's multimodal artistic conventions can work with the algorithmic techniques of computer science to blend the real and virtual worlds. We can then use the storytelling process to heighten the audience's perception, trigger imagination, and transcend augmented reality's current limitations. Projects such as Canon's AquaGauntlet first applied this mixture to AR technology in the form of video games. Technology based on the company's Coastar head-mounted display system provides our mixed-fantasy system's key component. Twin video cameras mounted on the HMD and aligned with the user's eyes feed real-world imagery to an image-processing system. The image processor - a pair of dual-processor PCs - then adds virtual imagery and feeds it back to the HMD. This video see-through technology articulates the virtual aspects of an entertainment product-such as characters, props, or effects-and blends them in real time to match physical reality. For group viewing and interaction, video-based technology also enables display options beyond the single-user HMD viewpoint. Blue screen mattingFrom proscenium portals to cinematic matte shots, the orchestration of middle ground, foreground, and background expands the illusion of immersion. The fidelity of the imagery can vary, but the tracking and registration must be precise or the illusion shatters. Accurately placing composites of roaming virtual objects and avatars in both the foreground and background in the physical set can be difficult when using only a head-tracking system. Any errors in head tracking produce exaggerated parallax errors due to the window frame's screening effect. Using a blue screen within a series of portals - windows or doors - supports real-time matting that masks imprecise tracking. The parallax then actually accentuates the dimensional illusion. For matting purposes, we have found that searching for a range of colours is insufficient, whether working in RGB or YUV color space. While such an approach works well in television and film studios with high-quality cameras and precisely controlled lighting, working under entertainment conditions with HMD cameras produces poor results. For example, only part of the blue screen might be interpreted as blue, and that portion could vary from frame to frame. We achieved stable and consistent matting only by seeking a range of colour ratios. Depth-mapping In real-timeUsing video see-through HMDs, graphics hardware can occlude virtual objects with real-world image pixels and replace real objects with virtual ones if depth can be computed accurately and quickly for real entities. Fortunately, the images captured by the Coastar HMD can be used to compute such depth from stereo coordinates (Akinari Takagi et al, "Development of a Stereo Video See-Through HMD for AR Systems," Proceedings IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Augmented Reality 2000, CS Press, Los Alamitos, California, 2000, pages 68 - 77). However, doing so for each pixel requires a computationally intensive process that yields unacceptable frame rates. Rather than computing the depth for all pixels, our extensions to Canon's MRPlatform API compute the depth for selected object markers, which are detected by colour. By restricting the search space, we achieve the speed required for real-time rendering. Additionally, our algorithms enhance the detected colour regions, the boundaries of which may vary with time. While the size of the colour region remains approximately the same, its centre tends to shift, resulting in variations of the computed depth. Downsampling the images dramatically reduces this variation. Using the downsampled images for depth computation only avoids adversely affecting the displayed video's quality. Special effectsWhen creating a mixed-fantasy experience, the physical world must be controlled along with the virtual. Theme parks apply audio, special effects, action equipment, and scenery to manipulate physical reality. This creates a tactile and visceral impact that can expand the user's scope of perception beyond the limits of visually based mixed-reality devices. Our system incorporates macrostimulators to produce a complex series of real-world sights, sounds, and other sensations that help validate the 360° illusion. Using macrostimulator events in a mixed-reality situation can jar the viewer's sensibilities in useful ways. A virtual adversary shoots out real lights, or its movements cause shutters to fly open with a floor-shaking thump. When all our senses validate a virtual event, the experience moves us across a credibility threshold. Audio immersion also emphasises events. The hybrid systems of surround sound, point-source display, and audiohaptic effects - which produce sounds you can feel - layer the audioscape and stimulate the peripheral senses. Homogeneous object pickingThe video see-through HMD makes it possible to use a simple laser pointer to select and interact with real or virtual objects uniformly. The video system determines the objects being selected without the need to first build a comprehensive 3D model or prewire an entire space with sensors. The system models and tracks only those objects relevant to the scenario. Using macrostimulator technology lets players cause changes to physical objects, thus diminishing the conceptual. distance between the real and the virtual. Scripting a deep experienceTo incorporate artistic collaborations that make it easier for nontechnical developers to create mixed realities, alter them dynamically, and monitor them as they occur, we developed a scripting environment that controls all aspects of the mixed-fantasy experience. This system communicates with the graphics engine, audio clients, and macrostimulator clients using Gilderfluke show-control devices. We use this system to develop a structured approach to storytelling in mixed reality. In doing so, we seek to blur the distinction between the real and virtual worlds still further. A central story-control system also lets us create a time-ordered record of all events that lets us monitor user actions and reason about system behaviour. The successful adoption of new technologies for entertainment applications depends on finding creative models that spark the imagination and generate demand. Developers must then apply these creative conventions to diverse business models, including theme parks, arcades, museums, and infotainment. MR Systems Laboratory, Canon, US Army Stricom, and the National Science Foundation all support work such as ours at several leading entertainment companies, providing an environment in which technical and creative innovation can act as equal partners. Christopher Stapleton is a director of Entertainment Research at the University of Central Florida's Media Convergence Laboratory. Contact him at cstaplet@ist.ucf.edu Charles Hughes is a professor of computer science at the University of Central Florida. Contact him at ceh@cs.ucf.edu Michael Moshell is a professor of computer science and director of the Digital Media Program at the University of Central Florida. Contact him at moshell@cs.ucf.edu Paulius Micikevicius is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Central Florida. Contact him at pmicikev@cs.ucf.edu Marty Altman is a research associate at the University of Central Florida's Institute for Simulation and Training. Contact him at maltman@ist.ucfedu Editor: Michael Macedonia, Stricom Source: Computer December 2002 Volume 35 Number 12; Computer is the membership magazine of IEEE (contact them at computer@computer.org - they specialise in "innovative technology for computer professionals"

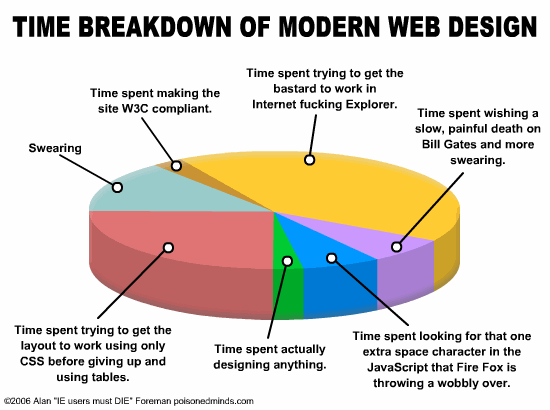

Source: poisonedminds.com

For IT-related articles on snooping, usage, the future, e-diaries, piracy, flickers, cyborgs, browsing, trends, jokes, philosophic agents, artificial consciousness and more, press

the "Up" button below to take you to the Table of Contents for this Information and Technology section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment