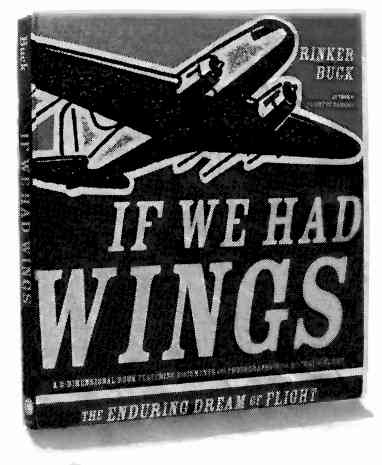

If We Had Wings

This Book Is Full of Midair SurprisesIt is about a period in aviation which is now gone, but which was probably more interesting than any the future will bring. — Charles Lindbergh, foreword to Listen! The Wind, 1938

review mostly by Jack Elliott If you've never dreamed of becoming a pilot, a reading of Rinker Buck's If We Had Wings may change that. It so thoroughly captures the excitement, the beauty, the romance of flight that long before you put down the book, you may wish you were part of that world. Buck has distilled the lore of aviation, from a dream 18 centuries before Christ of taking to the sky like birds to the incredible first landing on the moon, skilfully conveying the essence of man's conquest of the skies in each colourful chapter. This is not a conventional book It is printed in the style of collectible books, but it is not as large as most of them. Nor is it a thick, heavy volume: there are only 11 chapters, each a mere two pages on glossy, magazine-style paper with numerous illustrations. The contents have an element of novelty. There all kinds of little surprises tucked away in the pages. In the first chapter - "Dream of Flight," detailing man's fantasies about flying from thousands of years ago to the realisation of that dream by the Wright brothers in 1903 - there is a slit at the top of the right-hand page with a sheet of gray paper protruding. Pull out the paper and you discover a reproduction of the handwritten "High Flight," an extraordinarily beautiful and now legendary poem by Flight Officer John Gillespie Magee. He - was an American with the Royal Canadian Air Force during the early days of World War ll, before America's involvement. A few months after Magee sent the poem to his parents, on 11 December, 1941, his Spitfire collided with another aircraft over England and he was killed. He was 19. The reproduction is hard to read, but in the back of the book it is reprinted. Buck hits all the highlights of the story of aviation then and now. The chapter "First Flight" tells the story of Orville and Wilbur Wright's struggle to produce a powered, man-carrying flying machine. The little goodie in this chapter is an envelope containing a letter from bicycle mechanic Wilbur to the Smithsonian Institution dated 30 May 1899, revealing his belief that flight was possible (calling himself "an enthusiast, but not a crank") and requesting any material the Smithsonian had on the subject. World War I produced the first flying heroes - names like the Red Baron and Eddie Rickenbacker became legend. Aviation became an important part of warfare, and the war advanced aviation technology far more rapidly than peacetime would have. A chapter is devoted to this era. After the war came the era of "Daredevils & Barnstormers." And one extraordinary man, Jimmy Doolittle, made news by making the first "blind flight" - relying solely on instruments, a giant step for aviation. The early air mail fliers wrote an extraordinary chapter. Buck recounts one story, not widely known, of Jack "Skinny" Knight, a pilot who saved the air mail service of his time from extermination. Warren Harding was the incoming president, and he believed that the measly day shaved off the time of coast-to-coast rail delivery was not worth the extra 12 cents' fee, and he was determined to close down the air mail service. Mail planes flew only during the day, and then the mail bags were transferred to trains for travel at night. Night mail flights were hastily arranged - mayors of cities every 20 miles along the route were asked to light bonfires to guide the pilots. The mail was to be flown in relays. Knight took off from North Platte, Nebraska, for Omaha, where the next pilot would pick up the mail and head to Chicago. Knight flew below an overcast, his plane buffeted by ice and snow, but he made it to Omaha. Because of the storm, however, the relay flight never arrived from Chicago. Knight volunteered to fly the next leg. Mayors along the route were again telegraphed to light bonfires. He took off at 1am and reached Des Moines, but he couldn't land there because the snow was too thick. He followed railroad tracks to Iowa City where he landed and refueled. Knight took off once again and climbed above the storm, following the compass to Chicago. At dawn he was above the overcast and running out of fuel. He spotted a hole in the clouds and spiralled down through it. Right below him was his destination airport. It is courage and determination like Knight's that make aviation's story so dramatic. And it is such stories that are the soul of If We Had Wings. The book contains the World War II identification card of a WASP (Women's Airforce Service Pilot) certifying her as "an airman" and Captain Chuck Yeager's understated account of the day he broke the sound barrier. There are stories written by Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart and Howard Hughes and Roscoe Turner, neatly packaged in this easy-reading book. Buck (who learned to fly before he could drive) made aviation news himself in 1966, when he and his brother, Kern, then teenagers (he was 15, Kern 17), flew a Piper Cub they had bought for $300 and rebuilt. They flew from Somerset Hills Airport in Basking Ridge, New Jersey (now a condominium development) to California and back with no radio and only a compass for navigation. That adventure was told in an absorbing book, Flight of Passage, that Buck published a couple of years ago. If We Had Wings is a worthy successor. His love of flying and of the practical dreamers who "couldn't keep their feet on the ground" comes through. It has little to do with the current state of commercial airlines, which is why it seems so romantic. Source: The Sunday Star Ledger 15 July 2001 and USA Today Thursday 12 July 2001

To return to the page on the history of flight in the US, click the "Up" button below. However, if you came to this page directly from a referral, you might want to check out

the Index for this section to view other articles related to flying including history, unusual flying machines, hot air balloons, skydiving, gliding,

problems, airports, turbulence, pilots, crashes, the Paris Air Show, the future, blimps, space travel, solar sails and more. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment