Picking a Paradigm

Deliver MeGlobal capital markets pose the same kinds of problems that jet planes do. - Larry Summers

Airbus delivery area, Toulouse, Haute-Garonne, France (43°38' N, 1°22' E) Airbus’s factory in Hamburg, Germany, and its counterpart in Toulouse, southwest France, delivered 325 aircraft in 2001. Between them, they share the assembly of the European constructor’s five families of aircraft, soon to be joined by the superjumbo A-380, which will carry 555 passengers and come into service in 2006. Air transport is growing at 6%. It produces the highest emissions of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), which contribute to global warming. Passenger aircraft emit twice as much greenhouse gas per passenger mile as cars, and 6 times as much as trains. Freight aircraft produce 6 times as much CO2 as trucks and 80 times as much as ships and trains. To reduce the risk to the planet’s climate, world emissions of CO2 would need to be halved or cut to 1/3 of their present levels. This would involve, for each of the world’s 6 billion inhabitants, an annual quota of just 0.5 tons of carbon emitted into the atmosphere. At present, the average American emits 6 tons of carbon per year, a European 2 tons, and an Indian just 0.3 tons. Taking a single transatlantic air journey would be enough for an individual to use up this quota. Source: www.yannarthusbertrand.com from Earth from Above by the incomparable photographer Yann Arthus-Bertrand. Visit his site for some of the most stunning photos I have ever seen, of all kinds of things...

Airbus' proposal for a super-capacity airliner with seating configuration for 730 passenger. Source: www.lib.berkeley.edu Aircraft Interiors International March 2004

Airbus Comes of Age with A-380Europe's Big Hope for the Future of Airline Travel Takes Shape

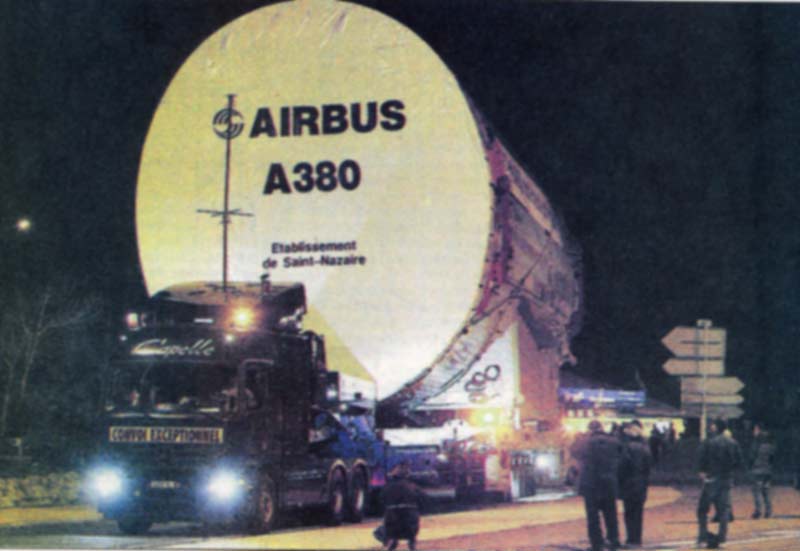

Jigsaw puzzle: One of the giant components of the Airbus A380 superjumbo makes its way to Toulouse for the start of assembly. by Kevin Done For the last three nights a convoy of huge trailers has been moving slowly and under heavy security along dark rural roads in the south-west of France, carrying with it the hopes of Europe's aerospace industry. Within days assembly of the' first A380 superjumbo, the biggest commercial aircraft ever to be built, is due to begin following the arrival this morning of the giant fuselage modules at a gleaming cathedral-like hangar beside the runways of Toulouse airport. The European aerospace industry's $12 billion gamble - backed by the governments of France, Germany, the UK and Spain - aimed at completing the overthrow of US domination of the world civil aerospace sector, is reaching its payoff, with the A380 due to make its maiden flight in less than a year. The towering green modules, each more than 10 metres high, up to 28 metres long and weighing up to 60 tonnes, have been in transit from Airbus plants around Europe for many days by sea, river barge and finally by road to the Toulouse assembly site. If it succeeds, the 555-passenger, double-decker airliner will cement Airbus's leadership over Boeing. Last year, Airbus delivered more aircraft than Boeing for the first time. With the A380, it is set to end the US group's lucrative 35-year monopoly of the large aircraft market and to create the most potent symbol yet of the power of cross-border industrial co-operation in Europe. To its doubters, however, the A380 will be a white elephant, searching in vain for customers. Critics say the aircraft is an overweight industrial dinosaur. "Is there any question that the A380 is a very expensive airplane for a very small market?" says Randy Baseler, marketing vice-president of Boeing's commercial air planes division. "We predict that the world needs only 320 very large airplanes [during the next 20 years] and not the 1,138 air planes that Airbus predicts." Airbus has recently raised its own forecast even higher to 1,163 with an additional 372 freighters. Such disputes underline the divide between Airbus and Boeing over air travel's future. While Airbus has opted for the giant A380, Boeing has gone for the 7E7 Dreamliner, a much smaller 200 - 250 passenger aircraft which it believes is what the world's airlines are looking for, rather than a behemoth. Pitched firmly in the middle rather than at the top end of the market, the 7E7 is in effect a replacement for the ageing Boeing 757 and 767 ranges, a segment where Airbus could be vulnerable as it only has its A330 - 200 to offer as competition. The companies also disagree on how airlines will accommodate growth in traffic, which both forecast will rise on average by just over 5% a year to 2022. Boeing's vision is based on the "fragmentation" of aviation markets, reflecting passengers' preference for more point-to-point, non-stop services and more frequencies instead of being routed to their final destinations via multiple connecting hubs. Adam Brown, Airbus vice-president for market forecasts, counters that "Boeing's numbers [are] pretty incredible." A recently published Airbus global market forecast for 2003 - 2022 says that "the total number of city-pairs served by mainline jets has stagnated." As airport and air traffic control infrastructure struggle to cope, "airlines will have to acquire larger aircraft." When Airbus made its business case for the A380 four years ago, it argued it would win half this market and that it would break even on a production of just 250 aircraft. For now it seems to have the market to itself, and it already has 129 firm orders from companies such as Singapore Airlines - which will fly the first A380 in 2006 - and Emirates, Virgin Atlantic, Lufthansa, Air France and FedEx. Mr Baseler claims such orders came with discounts of up to 40% off a list price of about $28OM. Not so, says Noel Forgeard, Airbus chief executive, who picked up a knighthood yesterday from Queen Elizabeth for his "outstanding contribution" to the civil aerospace industry. The British Queen was in Toulouse as part of her state visit marking the centenary of the Entente Cordiale - the deal that ended Anglo-French colonial rivalries. At Toulouse the 500-metre long assembly plant is claimed by Airbus as the biggest industrial building in Europe. The A380 is a project of many superlatives, but Airbus must still show it can generate superior profits. The same runways also saw the first flight of Concorde, another aircraft of technological superlatives, but a commercial disaster. Airbus and its shareholders, EADS and BAE Systems, cannot afford to repeat the mistake. Source: Financial Times Thursday 8 April 2004 photo credit Reuters

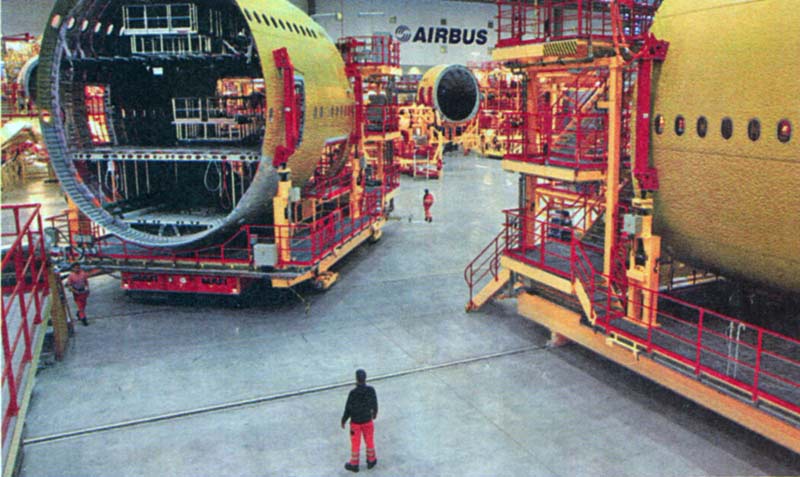

An assembly line at an Airbus plant near Hamburg, Germany, for the Airbus A380, a long-range plane with 555 seats that Source: The New York Times Tuesday 30 November 2004 photo credit Kai Wiedenhoefer

Luxury from Airbus?In the opinion of competent experts it is idle to look for a commercial future for the flying machine. There is, and always will be, a limit to its carrying capacity... Some will argue that because a machine will carry two people, another may be constructed that will carry a dozen, but those who make this contention do not understand the theory. - W J Jackman and Thomas Russell, Flying Machines: Construction and Operation, 1910

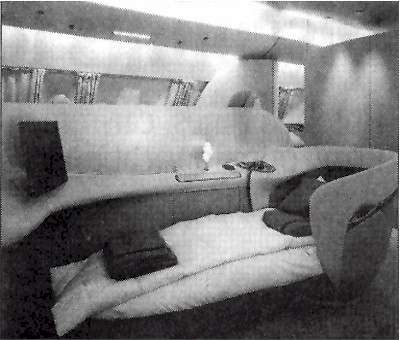

Bed and Board: Interior views of Airbus' concept plane show dining and rest areas. Airbus says space below decks will be available for other activities such as gambling and shopping. Sceptics say most of the ballyhooed amenities on the A-380, which could hold up to 800 passengers, will never materialise. "If there's room on an airplane, there'll be a seat in it," says Alan Mulally, president of Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Source: USA Today Thursday 21 June 2001 photos by Airbus

Click to play

Boeing Bets Big on a Plastic Planeby Michael Oneal and David Greising Boeing Company doesn't often let the public into its secured development centre. But on Tuesday, after months of bad news about defence scandals, trade wars and lost sales, the Chicago-based company finally had something to crow about. While the television cameras rolled, Boeing engineers unveiled a seamless, rivetless, one-piece barrel of carbon-fibre composite that has the unmistakable profile of a jumbo jet's back end. At 22 feet long and 19 feet in diameter, it is a crucial first step in a multibillion-dollar march to prove that the company can build its much anticipated 7E7 Dreamliner, the first passenger jet produced largely from the same kind of reinforced plastic used to make golf club shafts. The 7E7 is intended to replace the company's aging 767, which has been trampled in recent years by the A330, a jet built by Airbus. At 217 seats, it will be 20% more fuel efficient than the 767 and is designed to fly short and long-distance routes, bypassing congested hubs that routinely snarl air travel. The Dreamliner also will help rescue the company from a multiyear tailspin that has seen it slash jobs and fall to a demoralising second place behind Airbus in the worldwide market for passenger planes. Boeing hopes to see the 7E7 shuttling passengers through the skies by 2008. They face a long, difficult road ahead and Airbus is doing all it can to stanch its rival's momentum, including retrofitting the A330 with new wings and engines to compete with the 7E7. In 2003, Airbus delivered more commercial jets than Boeing for the first time. Over the past 12 months it has triumphed in one sales campaign after another, extending a winning streak that has allowed it to steal 21 percentage points of market share since 1999. Boeing hopes to slow the Europeans by negotiating a settlement to eliminate controversial government subsidies that have helped fuel Airbus' growth over the past three decades. Moreover, it has cut costs dramatically in recent years by slashing 39,000 employees and streamlining its production lines. But the company still had a problem. "It became really obvious that the business model has to change," explained Mike Bair, the 48-year-old Boeing executive who heads the 7E7 program. "Our customers can't make money with our product." Competing effectively with Airbus requires more than just eliminating subsidies and revamping the sales force. As the airline industry sinks into a crisis marked by bankruptcies, pension defaults and layoffs, Boeing must build a product its customers can afford. If the company's engineers solve the puzzle of building successfully with composites, they will eliminate hundreds of thousands of rivets, hours of machining time, and billions of dollars in expensive manufacturing machinery. That, in turn, should allow Boeing to price its new jet more competitively. Boeing has collected 126 orders for the 7E7 and is mitigating risk by outsourcing much of the jet's production to industrial partners around the world. But in the final analysis, the 7E7 is a massive gamble: If Boeing can make it fly, it has a good chance of revolutionising the way airplanes are built. To understand the debate about composites and aluminium, it helps to understand airplane architecture. The fuselage is built around a hollow, cylindrical skeleton like a birdcage on its side. "Frames" trace the circumference of the cage. "Stringers" run lengthwise, perpendicular to the frames. This lattice is enclosed by "skins" attached to the outside. Less than 1/4-inch thick in most places, skins are thin but if they were thicker, the plane couldn't fly. Skins, frames and stringers made of carbon fibre are lighter than aluminium but just as sturdy, reducing heft while increasing its strength. A composite fuselage won't corrode and can withstand greater pressure. It can be blown up to the equivalent of 6,000 feet of altitude rather than 8,000 feet, which decreases fatigue on long flights without increasing maintenance costs. The 7E7 can have a more humid cabin and bigger windows - a plus for passengers. And because composite structures are built by laying out thousands of thin ribbons of carbon fibre soaked in epoxy, it can be more versatile to use. Aluminium comes in sheets that must be machined while composites can be "laid up" in any direction or thickness. For the past four years, Airbus also has been pushing the envelope of aerospace technology as it spends $12 billion to develop a massive, double-decked airplane called the A380. When the 550-seat jet takes flight commercially in 2006, it will begin to usurp the lucrative superjumbo market Boeing has dominated for more than forty years with the 747. The A380 uses composites to knock 1.5 tons off the weight of the airplane's centre wing box, an essential structure that binds wings to fuselage. But Airbus decided composites cost too much to use in large structures like fuselage barrels. Instead, it relies on lightweight aluminium alloys, using a new material called "Glare," a sandwich of aluminium and fibreglass lighter and more corrosion-resistant than metal alone. Boeing's suppliers around the world are jittery about the company's plans. The fuselage and wing will be built by companies stretching from Japan and Italy to Texas. Each will be required to ship a completed section, "fully stuffed" with systems, seats and interiors intact. Boeing then plans to simply bolt them together. The final assembly process is slated to take only three days, far shorter than any other Boeing plane. The 7E7's development costs will come in at $7 billion to $10 billion, with about half coming from the supplier base. The aging organisation worried that if it didn't build a new airplane soon, it might forget how. In the end, the choice was clear: If Boeing was going to regain its momentum, its next product would have to change the rules of engagement. Composites could do that. Aluminium would not. If the engineers could invent a way to make a single, monolithic piece of composite for each barrel, the benefits would be enormous. Not only would single-piece barrels make for a lighter-weight airplane, they also would ensure that manufacturing one would be cheaper and faster. No rivets. No assembly. No expensive tools to hold pieces in place while they were being bolted together. The Boeing executives found what they were looking for in the oddest of places: a sailmaking company. North Sails Group LLC, one of the premier designers of lightweight composite sails for racing boats, had developed a machine that applies composite strips to a spinning barrel using multiple robotic tape-laying heads. The method was fast and, most important, scalable to something much bigger than a mainsail or jib. Boeing quickly licensed the technology from North Sails. Boeing built a 22-foot-by-19-foot cylindrical tube by piecing together six interlocking slabs of metal to form a mandrel. Mounted on a spindle, the mandrel spun while as many as 8 robotic tape-laying heads from a huge rack next to the mandrel spit out and applied the carbon-fibre ribbons. The mandrel slabs were built out of a special metal called Invar, carefully etched to provide the mirror image of the inside of an airplane fuselage. The slabs contain deep, lengthwise grooves so that premade composite stringers can be laid in before the composite skin is wrapped over them. On a rack next to this colossus are the tape-laying heads which apply layer upon layer of composite material as the mandrel spins. Once a fuselage barrel is wrapped around the mandrel, it has to be cooked for hours at around 250º to cure and harden. This is done in an autoclave, a pressurised oven the size and shape of a submarine. When curing is done, the mandrel is gently removed and a robotic cutting machine carves out the windows and doors. The moving is done with a massive Swedish forklift called the Max Move. So far, the barrel has stringers, but Boeing engineers still have to add the hoop-like frames to create the birdcage and speed up the process for production by adding more tape heads, then demonstrate that this elaborate waltz of rolling barrel and dancing tape heads can lay down composite material in precisely the right way each and every time. Even the smallest irregularity can cause a dangerous defect - wrinkles are a constant concern, for instance as are missing fibres. But the danger is mostly economic. If Boeing must layer on more composite material to make the fuselage sound or tweak the process endlessly to achieve the right tolerances, it could drive up weight and costs. The Europeans are convinced their planned retrofit of the A330 ultimately will prove more attractive to customers than Boeing's Dreamliner. The new Airbus plane, dubbed the A350, will have new composite wings and the same fuel-efficient engines that Boeing uses. The jet will weigh 8 tons less than the older model, have a range of 8,600 nautical miles (100 miles farther than the Dreamliner) and 28 more seats than the 7E7. It could burn less fuel per seat than Boeing's plane. The sales battle rages on. Source: story.news.yahoo.com Chicago Tribune Thursday 13 January 2005

The Fatal-Flaw Mythby James Surowiecki Every other summer, the aerospace industry gathers in Farnborough, England, for a big trade show. At Farnborough last week, there was one thing on everyone’s mind: the plummeting fortunes of Airbus, the European aerospace giant. Airbus is struggling to find customers for the new plane on which it has staked its future, the superjumbo A380, as airlines wonder whether anyone wants to fly on a jet that seats almost 600 people. The A380s that have already been ordered will be delivered late, thanks to production snafus that may add as much as $2.6 billion. Airbus’s other big project, the mid-size A350, is to be completely redesigned, at a cost of $10 billion. All the while, its sole competitor, Boeing, has been gobbling up business, thanks to its new mid-size jet, the 787 Dreamliner. In the first half of the year, Boeing took almost 500 new orders for planes, while Airbus took just 117. Airbus is a business-world anomaly. It was created in 1970, by an alliance of European countries, in order to break the American monopoly on the commercial-aircraft market, and it’s currently owned by a defense conglomerate in which the French government has a major stake. This connection has helped the company get access to government-subsidised loans, but has also meant that its corporate strategies have been shaped by politics. Now Airbus’s woes are being held up as proof that it is, in the words of one columnist, "a textbook example of how not to run a commercial enterprise." The Wall Street Journal explained that Airbus was failing because of its "politicized management," while the Times suggested that Airbus had to decide whether it was a company or a European "employment project." There are reasons to think that politics and business shouldn’t mix, but Airbus’s predicament isn’t one of them. What much of the talk about the inherent weakness of Airbus ignores is that, just a few years ago, it was Boeing that looked fundamentally flawed, while Airbus was seen as the future of the industry. Beginning in the late nineties, Boeing’s commercial-aircraft business went into a long and nearly profitless slump. In 2001, Airbus surpassed Boeing in new orders, a lead it maintained until this year. During that period, Airbus’s unusual structure was praised; its insulation from the stock market supposedly allowed it to invest in long-term research and development. Boeing, by contrast, was thought to be trapped in a short-term, cost-cutting mentality, because, as one analyst put it, "the money guys don’t reward long-term thinking and investment." In 2003, Business Week declared that Boeing was "choking on Airbus’ fumes," and warned that Boeing’s "slip to #2 could become permanent." The problem with such prognostications is that they infer basic truths about a company’s prospects from its short-term performance. In fact, present success is often determined as much by context and chance as by fundamental viability. This is particularly true of the aerospace industry, because success is heavily dependent on a small number of big gambles. If you bet right, you look like a genius for a few years, even if the success of your bet was due to factors out of your control. The 787 may now look like Boeing’s salvation, but Boeing built it only after more ambitious plans - for a plane, known as the Sonic Cruiser, that would have been the fastest passenger jet in the air - fell through, partly because of the slowdown in air travel after September 11th. And had Boeing not been in such straits in 2003 it probably wouldn’t have risked the investment required for the 787. People are generally bad at accepting the importance of context and chance. We fall prey to what the social psychologist Lee Ross called "the fundamental attribution error" - the tendency to ascribe success or failure to innate characteristics, even when context is overwhelmingly important. In one classic demonstration, people shown a person shooting a basketball in a gym with poor lighting and another person shooting a basketball in a gym with excellent lighting assume that the second person hit more shots because he was a better player. This problem is compounded by the tendency to extrapolate big conclusions from small samples, something that behavioural economists call "the law of small numbers." In the decade or so that Airbus has been a serious competitor to Boeing, this is its first really bad patch, and its difficulties are due mainly to making one bad bet while Boeing made one good one. That’s a minuscule sample size on which to base any kind of conclusion. But this is exactly what we like to do: sports fans assume that a few excellent performances are proof of a player’s underlying ability, while investors assume that a mutual fund’s record over one year is a reliable indicator of the manager’s skill. Because we underestimate how much variation can be caused simply by luck, we see patterns where none exist. It’s no wonder that management theory is dominated by fads: every few years, new companies succeed, and they are scrutinized for the underlying truths that they might reveal. But often there is no underlying truth; the companies just happened to be in the right place at the right time. In 1999, after all, it was hard to find a business book that didn’t hold up Enron as the embodiment of one important principle or other. Of course, some strategies and structures work better than others, but real meaning emerges only over the long term. Let’s give Airbus a few more years of floundering before we decide that it should be put out of its misery. Source: The New Yorker financial page 31 July 2006

The A380 Superjumbo: The White Elephantby Michael Harrison The latest Airbus, hailed as a model of European co-operation, is running two years' late. So will this project ever truly fly? The superlatives abound. It is wider than a football pitch and almost as long, 4 times the height of a double-decker bus, and weighs 560 tons. The A380 superjumbo is, in other words, large. Obscenely so, some might say, since the list price is an equally extravagant £166m - enough to build a hospital or three. Today, its maker, Airbus, will seek to reassure the world that the biggest airliner ever to grace the skies will be a commercial success when it enters service. But when exactly will that be? There could be no more pertinent question for Europe's answer to Boeing and, until recently, a shiningly successful example of cross-Channel industrial co-operation. A year ago, Airbus could do no wrong. It had outsold its American rival for the 5th successive year, and was looking forward to putting more clear blue sky between itself and Boeing, which was still struggling to recover from a succession of espionage, ethics and sex scandals of its own. Twelve months on and Airbus is in a mess. Appropriately enough, it is a big one. By now the A380 should have been in commercial service for the best part of a year. Instead, it is running two years late, leading some to describe it as aviation's latest white elephant. The blame lies with the wiring. Some 330 miles of cable and 100,000 wires weave through the fuselage, delivering power to the cockpit controls and in-flight entertainment systems. Connecting everything up is proving trickier than thought. The problem has already blown a superjumbo-sized hole in the profits of the parent company. But further delays could threaten Airbus's very existence, and along with it, tens of thousands of jobs and the many billions of pounds sunk into this grand project by the taxpayers of Britain, France, Germany and Spain. The plane was supposed to cost $10bn (£5.3bn) to develop - a lot for one aircraft, but a small price to pay, so Airbus and its sponsoring governments thought, for the chance to end Boeing's monopoly of the jumbo market once and for all. At the last count the development costs of the A380 had risen to $14bn. But the financial pain does not end there. In October, the company which ultimately controls Airbus, EADS, came out with some figures even more stunning than the vital statistics of an A380. EADS admitted that the delays on the aircraft would cost it an additional $6bn in lost profits, meaning that the A380 would not begin to pay its way until some time into the next decade. Airbus's latest 20-year forecast for the world jet market, to be published this morning, will put demand for the A380 at about 1,500 aircraft - almost 4 times the number that Boeing thinks will be sold. But that continues to look like an optimistic assumption, for everything appears to be conspiring against the A380, not least the value of the dollar, the currency in which all commercial aircraft are sold. When Airbus launched the programme 6 years ago, it needed to sell 300 aircraft to cover its costs. Because of the way the dollar has weakened, Airbus now needs to sell 420 planes. The order book stands at 149. The American mail company FedEx has become the first launch customer to cancel its order for 10 freighter versions of the aircraft, and at least one passenger airline has indicated it could follow suit. If the cancellations turn from a trickle to a flood, then the consequences would be catastrophic. The collapse of the A380 would be disastrous enough in itself. But the added problem for Airbus is that it needs the revenues the superjumbo is expected to generate in order to fund its next aircraft. This is an equally ambitious and expensive model, called the 350XWB (standing for extra wide-bodied). The plane, Airbus's answer to the new Boeing 787 Dreamliner, will cost another $12bn to build. Without those A380 sales, however, Airbus will be in a terrible bind. Tim Clark, the president of Emirates, says simply: "Airbus has got to produce a meaningful competitor to Boeing. If they don't, they will be out of business." It is all a very far cry from the self-congratulation and hyperbole which attended the formal roll-out of the first A380 from a Toulouse hangar in January last year. To the untutored eye, it looked like the finished article. But inside that giant cigar-shaped aluminium tube was a vast and empty void. Still, the plane looked the part, and the French President, Jacques Chirac, could scarcely contain his Gallic pride. Flanked by Tony Blair and his German and Spanish counterparts, he said Airbus should become the template for all future European industrial collaboration. After hubris like that, nemesis had to follow. And so it has. Fast-forward 20 months, and a very different image of Airbus emerges. It is hardly one that others are likely to rush to imitate. The revolving door has been spinning at those Toulouse headquarters, and Airbus is on its third chief executive since the summer. One of them, Noel Forgeard, was forced out with the whiff of insider dealing in the air after it emerged that he had sold shares in the parent company, EADS, shortly before Airbus dropped its first bombshell in June about the A380 delays. Mr Forgeard strenuously denies any wrongdoing. Worse than that, the company stands accused of being mismanaged, of being run as a series of shadowy fiefdoms, of having a culture which encourages the suppression of the truth and of playing fast and loose with other people's money. The indictment comes not from Boeing or one of its many supporters on Capitol Hill, but from Christian Streiff, a former executive with the French glass maker St Gobain, who was drafted in to head Airbus in July. Three months into the job, he came up with his master plan for rescuing Airbus: a combination of job cuts and an end to the cosy arrangement whereby production work had been shared out for political convenience. Mr Streiff's solution and his critique of the company's past failings were too much for the major shareholders, the French government and Germany's DaimlerChrysler, to swallow. Streiff was replaced by Louis Gallois, a technocrat and civil servant who won his spurs rescuing the state-owned rail company SNCF from the abyss. But it is worth recalling Mr Streiff's parting shot: "It is Airbus as a whole which failed, the management on several levels and with several passports who failed, and certainly not the teams on the shop floor. Airbus is not yet an integrated company." His words will have been as manna to the critics of Airbus, who look at the company and see not a sleek European corporate success story but a loose-limbed creature of government kept aloft by state handouts. A giant job creation programme, if you like. The contribution of the UK taxpayer alone towards the A380 programme is £530 million. In return for that, Broughton in North Wales and Filton near Bristol get to make the wings. But it also means that each completed set of wings has to make a remarkable journey to the final assembly site in France by way of container ship, river barge and specially adapted road trailer. With the main fuselage having to travel from Germany and the tailfin from Spain, no wonder Mr Streiff thought there was a simpler way. Analysts believe that Airbus may need to close down as many as half of its 14 production sites around Europe. One third of each new Airbus programme is funded by repayable launch aid from the taxpayer. This, and the fact that it does not have to answer to a conventional set of shareholders, may have played a part in the original decision to develop the A380. For the market for such a huge beast is unproven. In standard 3-class seating, the A380 will carry 555 passengers, which is 130 more than the biggest Boeing 747. Stripping out the galleys and making everyone sit 10 abreast, as some Asian carriers will be tempted to do, would increase capacity to more than 800 passengers. Virgin Atlantic, on the other hand, wants to convert the A380 into a flying gin palace, complete with on-board casinos and gymnasiums. The dispute between Airbus and Boeing over the size of the market for the A380 comes down to a basic difference in philosophy: would people prefer to fly point-to-point in smaller, longer-range aircraft, or will they be content to be herded 600 at a time on to a very big aircraft flying hub-to-hub, and then take a connecting flight to their final destination? Airbus says that economics and concerns about the environment will push airlines down the latter route as congestion at airports and constraints on carbon emissions force airlines to fly more people in fewer aircraft to keep pace with the growth of the overall market. Boeing, on the other hand, says people want greater choice and more direct flights. As evidence, it points to the collapse in sales of the 747 jumbo and the growth in demand for smaller twin-aisle aircraft. Should the A380 flop, it would merely be following in a long tradition. Concorde may have been a technically brilliant design, but it was commercially naïve. Only 20 were ever built, and of those just 14 went into service, losing the British and French governments the equivalent of what the A380 is costing today. It would be madness to write off Airbus in quite the same way. Disillusioned as its customers may be, they have a vested interest in ensuring its survival. Without Airbus, Boeing would have a complete monopoly over large commercial aircraft. Whatever happens, it is inconceivable that the French would let Airbus fail. As President Chirac said of the A380 at its roll-out in Toulouse: "This veritable ocean liner of the sky will go down in history like the Concorde." Perhaps not the best of analogies, but you know what he was trying to say. Source: news.independent.co.uk 22 November 2006

Airbus Order Revives Boeing Rivalryby Jorn Madslien Paris Air Show - Having just signed a deal that could signal the recovery of troubled aircraft maker Airbus, the chief executive of Qatar Airways knows full well he has thrown the cat among the pigeons. "I think you should be delighted that we are paying $16bn (£8bn) to a European company," Akbar Al Baker says. "Today we are really putting ink on paper for the purchase agreement." Ahead of the Paris air show, Airbus had failed to secure more than 13 orders for its mid-size, long-range A350 WXB, a rival to American aerospace giant Boeing's 787 Dreamliner, which had already clocked up 584 orders. In placing an order for 80 of the expensively redesigned A350s, Qatar has revived the rivalry between the two companies, despite much talk of the Airbus plane's faulty design and delayed arrival in the market place. "This project is taking off in the best way," declares a beaming Louis Gallois, chief executive of Airbus. "Now we are at the beginning of a new story." Having announced more than $45bn in orders during the first day of the show - equivalent to what analysts had expected from all the aircraft-makers here combined - it seems Airbus' deal-makers have defied gravity in a manner only matched by the A380 super-jumbo's spectacular air display. The giant 555-seat aircraft still turns heads, two years after its first fly-over in Paris, though there are many who bemoan the fact that the big bird has yet to be delivered to customers. The A380 delays, which have been caused by wiring problems, have cost Airbus dear and sparked concerns about the company's ability to deliver the A350 on schedule. Mr Gallois is eager to ensure airlines that this time all is under control. "We have learnt a lot [from the problems with the A380], and you can be sure we will take care of that," he says. "I don't like the campaign right now that the [A350] aeroplane is not defined. It is defined, performance is defined, we are committed to achieve the performance, and we are offering guarantees to our customers." No DelaysBoeing's technologically advanced Dreamliner is set for a debut on 8 July and "we expect to deliver the first 787 in May next year", Scott Carson, head of Boeing's commercial airplanes division, tells BBC News in an interview. Airbus lags far behind, with an estimated arrival date of 2013. But at this stage the choice between the two aircraft has become easier for buyers since Boeing's swelling order book means it is operating a waiting list for new orders. In other words, regardless of which plane a carrier was to choose at this stage, they would probably not take delivery till 2013 in any case. Consequently, the two aircraft makers are back on a level-playing field as they vie for the attention of Emirates, which is planning to place an order for 100 aircraft. The airline says it will place the entire order with just one of the companies, choosing either the A350 XWB or the 787 Dreamliner. "We've got some talking to do to both Boeing and Airbus with regard to the commercial terms of the deal," says Emirates president Tim Clark. "But I think we're in a good position to make an aircraft decision in the next few months. Some observers say Qatar could also be in the market for more aircraft, though when asked whether he would be placing orders with Boeing anytime soon, Mr Al Baker remains mum. "You get Mr Gallois worried when you talk about Boeing," he quips. "You shouldn't be talking about Boeing here." AIRCRAFT DELIVERED IN 2006 Source: news.bbc.co.uk 18 June 2007 For lots more on the conflict between Airbus and Boeingm see also:

To view other articles related to flying including history, unusual flying machines, hot air balloons, skydiving, gliding, problems, airports, turbulence, pilots, crashes, the

Paris Air Show, the future, blimps, space travel, solar sails and more, clicking the "Up" button below takes you to the Table of Contents for this section on Flight. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment