Is It Really Training in Disguise

Looking through Philosophy's WindowBeware of the man who works hard to learn something, learns it, and finds himself no wiser than before. He is full of murderous resentment of people who are ignorant without having come by their ignorance the hard way. - Kurt Vonnegut Jr

Learning to think independently is supposed to entail more than simply visiting the library by Lisa Kearns "The skill that gives (job) applicants the winning edge is a capacity for independent and critical thinking; this is what employers are looking for." So said the federal Minister for Education, Dr David Kemp, commenting on a report on employer satisfaction with graduate skills by A C Neilsen, commissioned by the Education Department earlier this year. What exactly is independent and critical thinking? Why is it valuable to be able to examine your thought processes? How can students, clamoring for a piece of the job pie, achieve this economically desirable attribute? In true philosophical fashion, Tim Oakley, a senior lecturer at the LaTrobe University school of philosophy, questions what Dr Kemp means by independent thinking. "I suspect that what is meant there about independent thinking is not what we (philosophers) mean," he says. "Similarly, people talk dangerously about team players and team thinkers, people who can work together, but I think what they mean is people who will take orders." Mr Oakley is among those who are disappointed that much-vaunted changes to the school system have failed to produce university students who can truly think for themselves. "Some students are very slow, very unwilling, to take up the idea of expressing their own opinion - even if it's in an essay they know only (their teacher) is going to read," he says. "And (teachers) don't just want evidence you understand the problem, we want your judgment on the problem... the trouble is, I fear, that independent learning to some means going to the library on your own and looking up information, rather than independent learning in the sense of developing your own views." Professor Graham Priest, professor of philosophy at the University of Queensland, but soon to become professor of philosophy at the University of Melbourne, adds: "Because students are acclimatised like this in schools and in a number of university departments as well, a lot of them founder when they come to philosophy for the first time." In the education system in our society, according to Professor Priest, children are generally not educated to think for themselves; they are educated to fit in. And as long as people keep being socialised to be followers - and not to question assumptions about a range of "big ticket" issues like religion, morality, government, child-rearing - we'll keep getting the phenomenon of exploitative leaders and the exploited masses. "What is valuable about philosophy is it can attack this attitude," says Professor Priest. "It makes each individual think, 'hey, I'm not stupid! I can think through this issue for myself. I can make up my own mind on the basis of what I read and what I know. I don't have to believe this simply because this is what my father thinks, or my priest, or my philosophy teacher'." What is education? What is the value of education? These sorts of questions are also firmly in the domain of philosophy. The conception of "education" that is emanating from government policy and the capitalist market-driven system in which it operates is now more akin to "training", says Professor Priest. "You chisel a cog to fit the right shape and send it off to industry. When it wears out, you throw it away. In other words, the social worth of education is being replaced by the economic worth of functioning within the capitalist system." The problem-solving skills and the ability to think things through that studying philosophy can impart are valuable at any time of life, says Professor Priest. To explain the value of philosophy, he says, imagine yourself in a mediaeval society hundreds of years ago: the status of the monarchy was not questioned; the status of women as being naturally inferior to men was not questioned. "What we believed 600 or 700 years ago, we don't believe now; what we will believe in 1,000 years will be very different from what we believe now. So the first thing (in studying philosophy) is to get people to unravel these things. The second is getting people to realise these are contingent assumptions. They are not fixed indelibly in human society or human thought. When you've done that, you can start thinking about whether or not these things we take for granted are actually true, or good. For example, what is it that you want out of government process and state? How is that best achieved? "We don't really ask those questions because they are partly too hard and too dangerous. Often the answers are subversive! But everyone needs to learn to think for themselves because there are real dangers in following a leader. Democracy, which actually means getting people involved in decision-making processes affecting their lives and coming to some consensus, is really valuable." At the 10th Australasian Philosophy in Schools Conference in Melbourne last month, a comment from a secondary student was highlighted: "Each high school subject seems to show the world through a distinct window unconnected to the window presented by other classes. Philosophy, on the other hand, attempts to look through all the windows at once." More students are enrolling in philosophy subjects at tertiary level, and this looks set to continue with philosophy becoming a VCE subject (units 3 and 4, at year 12 level, will begin next year). Academics expect a greater number of student teachers, interested in teaching philosophy at year 11 and 12, to enrol in philosophy subjects as well. In addition, there's always been a strong contingent of mature age students, a sizeable number of them teachers, simply interested in the subject. This is not to say that philosophy is a dead-end, wishy-washy, abstract subject of little use in the work-a-day world. Philosophy graduates turn up everywhere in industry. Many go into law, media, education and politics. A good number do more unconventional things, even "drop out" for a while, perhaps because they are not so enamored of prevailing social structures and want to think about ways to help change them. Dr Laurance Splitter, director of the Centre for Philosophy with Children and Adolescents at the Australian Council for Educational Research, says children are perfectly capable of adopting philosophical models of thinking things through if they are in a supportive environment. Dr Splitter, author of books such as Teaching for Better Thinking (with Ann M Sharp) and Places for Thinking (with Tim Sprod) says philosophical thinking gives children, "actual thinking tools, or armor, that will help give them a structure to think about things - like drugs, for example - later on in adolescence." Professor Priest and Mr Oakley agree that the ability to question starts very young, at least on a par with language development. "The ability to understand answers comes very gradually, but the questioning spirit is there all the time," says Priest. "It is important that this be encouraged and reinforced and given the tools to work rather than be repressed or frustrated." Source: The Age education section Wednesday 18 October 2000

Thinking Is the Best Way to Travel!

Source: sciam.com by Scott Orimando

To Create Generalists, Teach Students How to Learn by ThemselvesEducation's purpose is to replace an empty mind with an open one. - Malcolm S Forbes Sir - In his Millennium Essay, Frederick Seitz[1] makes a compelling case for the importance of generalists - individuals with broad vision - in all cultural fields, and he laments that their ranks are thinning. I subscribe entirely to Seitz's assessment, yet I disagree with his analysis of what causes this trend and with his suggested remedy: reforming elementary and secondary education. It has become almost a cliché in the United States and Europe to blame schools for society's increasing cultural ignorance. Yet many schools have struggled for years to maintain a diverse curriculum, despite budgetary constraints and conflicting societal demands. Even so, a school's ability to affect students' cultural breadth is very limited. Children spend most of their time with family and friends, not at school. Parents need to provide daily evidence that they value diverse cultural pursuits: if they let their children devote an inordinate amount of time to a narrow range of activities, schools cannot be expected to produce people with differing values. Provided parents have planted the seed of cultural and intellectual curiosity in their children, there is little that colleges and universities can do to kill it, but they can nurture it to a lesser or greater extent. Seitz considers that university teaching staff have virtually no room to manœuvre against the strong internal and external forces that promote specialisation. Chief among these, according to Seitz, are "conditions of intense competition", which leave little time for scholars to cultivate new, diverse interests. Examples abound, however, of scholars such as Einstein, Jaynes and Mandelbrot who gained prominence and significant competitive advantages in their field precisely because they were able to borrow concepts, tools and methods from disciplines far from their own. The growing complexity of most fields of research, which Seitz also mentions as an incentive to specialise, has to be put in historical perspective. A century and a half ago, scholars in North America and Europe were expected to be well versed in all branches of knowledge, and to remain so during their whole lives. Admittedly, most fields of research have become much more complex since then, but the level of specialisation of most scholars has increased incommensurably. I believe that colleges and universities are responsible for this, not because of pressures on them but because of their approach to learning. By the second half of the nineteenth century, undergraduate education was in many respects similar to what we have now and, except in a handful of English institutions such as Oxford and Cambridge universities, did little to equip students with the skills necessary to keep learning new disciplines and updating their knowledge. On the other hand, an old tradition of "self study" in society at large provided them with these skills[2]. Early graduate programmes in Germany and, for a time, at Johns Hopkins[3] emulated this in their system of "self education under guidance". In the early part of the twentieth century, however, universities eradicated self-directed learning from the educational landscape. They successfully promoted the idea that quality learning can occur only in the physical or, more recently, "virtual" presence of a teacher. With rare exceptions[4, 5], colleges and universities nowadays do not prepare students to keep learning on their own after they leave college. As a result, many graduates (including many who become academics) find that their lack of skills renders learning inefficient and slow. The best they can do is to deviate as little as possible from the narrow trajectory on which they were placed during their initial training, or retraining in the private sector. To alleviate the resulting cultural and intellectual atrophy, colleges and universities must rethink their attitude towards self-directed learning, and implement imaginative ways to foster it effectively. Philippe Baveye Laboratory of Environmental Geophysics, Bradfield Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 USA and School of Education, University of Paris X, 92001 Nanterre, France [1.] Seitz, F Nature 403, 483 (2000) Source: Nature Vol 404 23 March 2000

Preschoolers Who Take Responsibility Do Better Later OnA new study published in Journal of Personality finds that parents who provide their preschoolers with choices and encourage them to take on responsibilities were helping their children in the long run. This pattern of parenting called "autonomy supportive" was shown to lead to high academic and social adjustment in 8-year-olds. Teacher reports and standardised tests showed that this flexible and responsive parenting technique that focused on the child's perspective, explaining the rationale for requests, providing choices, and not using controlling language lead to better outcomes. "Autonomy support was found to increase the odds of children being both high in social and academic adjustment, as well as high in both social adjustment and in reading achievement," the authors state. The results held true regardless of socio-economic status, gender, or IQ. The study interviewed the mothers of 5-year-olds to measure the level of autonomy support and other parenting dimensions. Three years later, the study looked at the children's social adjustment and achievement in reading and math in grade 3. "Maternal autonomy support measured in kindergarten was positively associated with social adjustment, academic adjustment, and reading achievement in 3rd grade," the authors cite as their most important finding. This article was published in the August issue of the Journal of Personality, which publishes scientific investigations in the field of personality focusing particularly on personality and behavior dynamics, personality development, and individual differences in the cognitive, affective, and interpersonal domains. Mireille Joussemet is an assistant professor in Child Clinical Psychology at the University of Montreal. She has extensively examined the role of parents and teachers in promoting children's internalization of values and guidelines. She has recently focused on the role of parents in teaching children to inhibit their aggression. Dr Joussemet is available for questions and interviews. Richard Koestner is a professor of psychology at McGill University. His graduate research focused on the motivational effects of rewards and praise. He has published over 80 scientific articles in the areas of human motivation and personality. Dr Koestner is available for questions and interviews. Source: eurekalert.org 2 August 2005

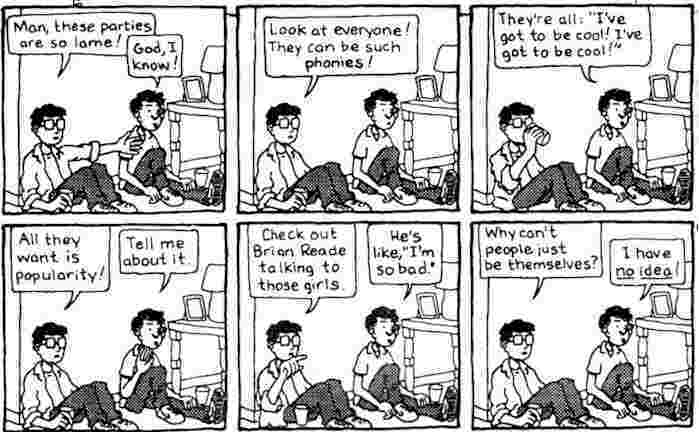

The Education of Louis

Source: Funny Times date undenoted

For articles on education covering subjects taught, tests, costs, boredom, honour, rites of passage, rigid rules, cliques, thinking, learning, homeschooling, creating, brilliance,

ongoing education and more, click the "Up" button below to take you to the Table of Contents for this section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment