How Important Are Animal Feelings

Are Animals Conscious?To a teacher of languages there comes a time when the world is but a place of many words - Joseph Conrad

Answers: "Yes," "No," "Maybe," and "It all depends..." One of the reasons it is unclear whether or not animals may properly be said to be conscious is that the term has no universal definition as applied to humans. Is consciousness equivalent to awareness? To attention? Cognition? Perception? Memory? Imagination? All of these? Much more? To attempt to apply a vaguely-defined term to non-human species merely compounds the confusion and makes it a virtual certainty that any attempt to answer such a question is a waste of time. The topic has become virtually taboo in serious science, with most investigators polarised into opposing camps of "definitely so" and "no way!" Believers in one group vehemently reject the results of the other, and no one seems able to mount a convincing case; but that is not to say that scientists (and others) have stopped making the effort. Few topics today are as divisive as the role non-human animals play in ideas about religion, society, law, morals, research and even in the home. On the one hand are the Cartesian groups, who feel that animals exist merely to serve their masters, namely humans, in whatever way possible - whether furthering the bounds of human knowledge or acting as dinner. On the other hand are the Animal-Liberation-Front-type militants who firebomb property, issue death-threats to researchers, and turn animals loose in habitats into which they do not fit, wreaking havoc all around. Surely a middle ground exists? Why might the answer to the question of animal consciousness be important? First, philosophy often begins with the question of man’s place in nature. One way humans locate themselves is by comparison to those things they find to be most similar (Allen). Moreover, the answer to the question of animal awareness would extend the bounds of human knowledge and allow us to better test various theories of human consciousness. It would also determine proper laws on the care, rights, and consumption of animals. Finally, it would help to clarify when a human could legally be considered "non-conscious" (as opposed to merely unconscious), thus helping to illuminate what should be the rights of non-conscious humans (such as Terri Schiavo, who, after 15 years in a "permanent vegetative state," had her feeding tube pulled against the wishes of her parents - a move which polarised the US and ended her life). Movies such as Soylent Green (see Note below) to the contrary, it is unlikely that non-conscious humans (unlike presumed non-conscious animals) will ever be considered a source of nutrition. What has been the attitude toward animal consciousness in the past? In Izaak Walton’s classic The Compleat Angler, first published in 1653, the pike is described as "the tyrant of the rivers, or the fresh-water wolf, by reason of his bold, greedy, devouring disposition; which is so keen" (122). But did Walton intend to imply a true awareness on the part of the pike? A little clearer is John Donne’s position: he noted in a 1628 sermon, "The beast does but know, but the man knows that he knows" (Carter 143). Many scientists today feel this so-called "second-order consciousness" (knowing that we know) is really what sets man apart from other animals. But not all scientists agree that it is second-order consciousness that is critical. Some think it is instead complexity of thought. The beginning of order in brainwaves appears in creatures as lowly as the earthworm. More sophisticated brain-imaging equipment has allowed the discovery of the presence of non-linear computation in the brainwaves of more advanced animals, with values varying according to phyla complexity in a logical progression. Further, this complexity increases with higher levels of arousal and even with the maturity of the animal in question (Walling and Hicks 165). So, is consciousness a measure of complex brain activity? Or is it rather complex behaviour which is the key? Even the lowly cow is now known to become excited by solving intellectual challenges. In one study, researchers presented the animals with a task - they had to figure out how to open a door to reach a food reward. The scientists used an electroencephalograph to measure the cows’ brainwaves. When successful, their brainwaves showed their excitement; their heartbeat went up and some even jumped into the air (Leake). Keith Kendrick, a professor of neurobiology at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge, has done similar experiments on sheep. The emotional sympathy of a sheep is extraordinary - when they sense human anger they flee. Good shepherds talk to their sheep and move slowly. Sheep answer him: they bleat when hungry, cry when distressed, whicker affectionate noises to reassure their lambs, grunt when curious, whistle when alarmed or hostile, and groan in pain when giving birth. Sheep can remember 50 ovine faces - even in profile. They recognise another sheep after more than a year apart. Kendrick has also described how sheep form strong affections for particular humans, becoming depressed by long separations and greeting them enthusiastically even after as long as three years. When sheep are isolated, showing them photographs of the faces of familiar sheep helps to soothe them (Leake). The same principle applies also to dogs. Some dogs really don't like being left by their owners. One way of keeping them calm and stopping them trashing the place is to provide them with their master’s photograph, prominently displayed. But complex behaviours, however entertaining, may not be enough to demonstrate consciousness. In the views of most scientists language would be a conclusive demonstration of consciousness. An important question, therefore, is can non-human primates be said to know language? That question may be no easier to answer than the one about consciousness. Reactions to the question of language use in primates ranges from bored indifference to accusations of fraud to rhapsodic testimonials. An example of the latter reaction - about an orangutan named Chantek who knows sign language - is as follows

Words, for orangs, are not exactly precise. For Chantek, the sign for "bug" includes several things: crickets, cockroaches (even a picture of a cockroach), beetles, slugs, small moths, spiders, worms, flies, tiny brown pieces of cat food and even small bits of fæces. He signed the word "break" before he crumbled and shared pieces of his cracker and also after he had broken his toilet. He signed the word "bad" to himself before he grabbed a cat, after he bit into a radish and also when he discovered a dead bird (Addeyman). Chantek is (so far) one of the lucky primates. Consider Lucy, a chimpanzee who was initially a pet; when she grew too large for her owner, she was donated to research and became a test subject. Lucy learned American Sign Language. She proved to be smart and personable and greeted her human teacher every morning with a big hug and two cups of tea which she prepared herself at the stove she was allowed to use. But acting "almost human" didn't provide Lucy with any protection. As too often happens when aging chimps become hard to handle as pets and/or outlive their usefulness as study subjects, Lucy was sent off to a chimpanzee rehabilitation centre in Africa. There, poachers shot and skinned her, then cut off her feet and hands as trophies (Staff C01).

Koko, a well-known signing gorilla, loves to paint. The first painting is her picture, Pink; Consciousness, most theorists agree, equates to the use of language: language enables a person to know himself, to see himself as others see him, to become self-aware. If one is a Lanierist (linguist Jaron Lanier feels that consciousness, as evidenced by the use of language, traps us in time, in "the very concept of a present moment") one can argue that man has given Chantek, in the gift of language, a more terrible prison than the steel one: the jail of the present, with its sharp edge. ("Now Lyn is here," Chantek must hear in his head, "And now she is leaving.") Conversely, one could argue along with Bickerton (linguist Derek Bickerton wrote, "Only language could have broken through the prison of immediate experience in which every other creature is locked, releasing us into infinite freedoms of space and time") that the doors of Chantek's cage have been flung open in a way no key could ever do (Antonetta). It is at this point impossible - but would provide a profound enlightenment - to hear Chantek's internal dialogue. Many animals recognise words, but their memories must be stored as pictures. Could it be that Chantek files away information in signs - the equivalent of words? On a rainy day, with nothing to do, does he relive past experiences? Remember past conversations? Plans are underway to connect up the widely-scattered sign-language-using orangs, gorillas and chimps with video monitors to see if they attempt to converse with each other.

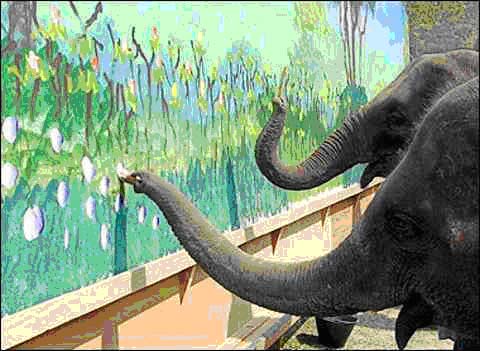

Eight elephants in northern Thailand have painted their way into the Guinness Book of World Records after an art lover in the US shelled out 1.5 million baht Elephants obviously cannot be taught sign language - but they have an unusual ability to mimic and learn new sounds which scientists believe are used as a form of "acoustic communication." Joyce Poole, of Amboseli Elephant Research in Nairobi, Kenya, has said that elephants are capable of imitating sounds, including those not normally part of elephant repertoire. She and her colleagues recorded a 10-year-old African female elephant who imitated truck sounds - the elephant’s overnight stockade was located about two miles from the nearest highway. The elephant, it was realised, would mimic truck sounds for several hours after sunset. This is the best time for transmission of low-frequency sounds, so it is when herds in African savannahs attempt to communicate with each other. In a similar case, a 23-year-old African male elephant, raised among Asian female elephants in a zoo in Switzerland, learned the chirping sounds which are typical of Asian (but not African) elephants. "He was probably trying to be part of that social group and to join in with them," said Poole in the science journal Nature. (And perhaps the first elephant thought the trucks represented a nearby herd of immigrants.) "It is yet another sign they are very intelligent and their communication is very complex" (Reaney). (I read recently where the sound of helicopter blades could send elephant herds into a frenzy even though they were several miles away.)

Surprisingly, one of the most prolific users of language has turned out to be African grey parrots. Dolphins and sea lions differentially respond to statements such as "Touch the surfboard that is grey and to the left" versus "Swim over the Frisbee that is black and to your right." But researchers have worked with a grey parrot named Alex who responds correctly to questions such as "What object is green and 3-corner?" versus "What colour is wood and 4-corner?" or "What shape is paper and purple?" According to Irene Pepperberg, research associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Brandeis University:

Pepperberg says that researchers hide objects under cups - the equivalent of shell games played at carnivals. Alex understands that "out of sight" does not mean the object ceases to exist. When they switch the cups around, Alex still finds the hidden object. Once they deceived Alex by pretending to put the object under a cup but actually placed it under a different cup. The bird picked up the cup where he expected the item to be. When the item (a nut) was not there, Alex banged his beak on the table and began tossing the cup around in anger. Alex showed clearly that he had expectations because he thought he knew something, and this had been violated (Pepperberg). If animals are conscious, would that give them rights? Tibor Machan, a philosopher and professor of business ethics at Chapman University in Orange, California, who has written about the issue of potential animal rights, argues that the criterion for rights is morality. "Such rights would only arise if animals developed into moral agents, which they haven't," he says. "Notice no one is expecting animals to be kind, compassionate, considerate of their own victims, stop being carnivorous if they are, and so forth. That's because the only moral animals are human beings" (Staff C01). (Note that some humans don’t meet those criteria either. Machan does not indicate if he thinks humans who are not moral agents do not have rights, although this would be a logical progression.) A unique perspective is provided by Dr Temple Grandin, a professor in the Department of Animal Science at the University of Colorado, who herself suffers from autism. She notes that some scientists believe that while animals may possess a degree of consciousness, it is a type of "animal consciousness" which is surely radically distinct from any form of human consciousness. Dr Grandin points out that, as a person with autism, she possesses a consciousness that is radically distinct from that of normal people. Does this make her less human? Grandin says that she does not think to herself in words, but in pictures. She does not use language internally to form thoughts or to reason herself into a decision. Grandin considers the possibility that consciousness may be a compound of several awarenesses. In animals, perhaps only one or a few of these components are functional. The higher up one goes, the more the complexity of consciousness increases. She feels that perhaps scientists, unable to agree on what consciousness IS, should instead try to agree on what it is not. "It is not a reflex, it is not simple conditioning, and it is not a hard wired instinct which works like a computer program. Conscious behaviour is flexible. Conscious behaviour allows animals to make choices between different options" (Grandin). Grandin feels that some language-based thinkers have trouble even accepting that animals think as it seems impossible to them to be able to "think" without words. While some philosophers can accept that an animal may have memories without language to represent them, they don’t accept that an animal can have beliefs and desires like a human can and therefore it cannot possibly be considered conscious. But Grandin feels that she herself lacks some of the second order consciousness that many scientists feel sets humans apart from other animals. She states, "If I say I desire chocolate cake I immediately see a slice of cake. In fact I see it at a particular cafe. Desire has no abstract meaning. I just see pictures of things I would want such as an ice cream cone. I use the word belief to describe things where there is a high probability that something may be true, but I am not 100% sure" (Grandin). She feels there are four basic levels of consciousness - within one sense; where all senses are integrated; where all senses integrate with emotions; and where senses and emotions integrate and thoughts are in symbolic language. She feels that her personal consciousness reaches only to level two as her thoughts are not linked to emotions and are not normally in symbolic language. She feels a hierarchy of consciousness (rather than on on-off state) is most reasonable because damage to the nervous system damages (but does not always destroy) consciousness. There are many humans with marginal or non-existent levels of consciousness, including toddlers, those with advanced cases of Alzheimer’s, autism, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, spina bifida and others. These people have a right to live and a right not to suffer. They are incapable of "norm-guided logical or practical reasoning, moral self-legislation, and reflective self-consciousness" (Hanna); though they may possess emotional complexity, they have impaired or lacking language skills. Some animals rank higher on those scales than some humans. Morally, should we care as much about apes (and possibly other primates), whales and dolphins as we do about victims of defect, immaturity and disease? And if not, why not? The effort spent on debating morally about stem cells, very early-stage fœtuses prior to sentience, lower animals, and humans in persistent vegetative states or anencephalic, may be a greater waste of time. In conclusion, lacking proof, one can really only take a position on the matter of animal consciousness. Here is mine: To me, as everyone in the world is unlikely to turn vegetarian overnight, the most important agenda item at this point should be to make the deaths of all animals, when death is necessary to impose, as stress-free and painless as possible. In New Zealand, even salmon are sedated before they are killed. Some animal shelters have begun anæsthetising animals before they are euthanised. Slaughterhouses could do the same. Their employees would benefit as well. Note:The movie Soylent Green, produced in 1973, was set in the year 2022 when earth had completely changed. New York had 40 million hungry people; the greenhouse effect had caused temperatures to soar until the world outside was nearly unbearable. The wealthy among the population lived segregated in luxury apartments, occasionally paying $150 for a cup of real strawberries. The Soylent Corporation fed everyone with a type of cracker which came in flavours: Soylent red, yellow, or especially green (considered by all to be best). What was the source of Soylent Green? Well, let’s just say it was no longer soybeans or plankton... Works CitedAddyman, Caspar. "Linguistic Superabundance." 31 August 2000. <www.onemonkey.org/history/000831.html>. Allen, Colin. "Animal Consciousness." The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2004 Edition). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). <plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2004/entries/consciousness-animal>. Antonetta, Susanne. "Language Garden", Orion Magazine, March/April 2005. 19 March 2005. Carter R. Exploring Consciousness. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. Grandin, Temple, PhD. "Consciousness in Animals and People with Autism." October 1998. <www.grandin.com/references/animal.consciousness.html>. Hanna, Robert. "What Is It Like to Be a Bat in Pain?: Kinds of Animal Minds and the Moral Comparison Principle." <spot.colorado.edu/%7Erhanna/bat_in_pain_dft1.htm>. Leake, Jonathan. "The Secret Life of Moody Cows." The Sunday Times, 27 February 2005. <www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2087-1502933,00.html>. Pepperberg, Irene. "That Damn Bird." 23 September 2003 <www.edge.org/documents/archive/edge126.html>. Video source <www.alexfoundation.org/alextheparrot.mov>. Reaney, Patricia. "Elephant Learned to Mimic Truck Sound - Study." 23 March 2005. < today.reuters.com/news/newsArticle.aspx?type=scienceNews&storyID=2005-03-23T190816Z_01_N23178204_RTRIDST_0_SCIENCE-SCIENCE-ELEPHANTS-DC.XML> Staff Writer. "Beastly Behavior." Washington Post, 5 June 2004. Walling, Peter T., MD, and Kenneth N. Hicks. "Dimensions of Consciousness." Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings Volume 16 Number 2, April 2003. Walton I. The Compleat Angler; or, the Contemplative Man’s Recreation. London: JM Dent and Sons Ltd, 1962.

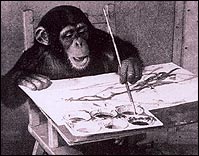

Bidders Go Bananas for Chimp's Paintings

Congo the chimp creates a masterpiece Paintings by a chimpanzee netted more than £14,000 today after going under the hammer alongside works by Renoir and Andy Warhol. The 3 abstract pieces up for auction at Bonhams in London were painted by Congo in 1957 and were estimated to fetch between £600 and £800. But bidders went bananas for the pieces - which were sold as one lot for £14,400, including buyer's premium. A spokesman at Bonhams said there had been a "fantastic" amount of interest in the chimp's artworks. They were bought by an American man named Howard Hong, who described himself as an "enthusiast of modern and contemporary painting". The chimp produced about 400 drawings and paintings in the late 1950s after being encouraged by animal behaviourist Desmond Morris. He was a regular guest on Dr Morris's television programme Zoo Time. The experiment convinced Morris - who achieved fame for his television series and best-seller The Naked Ape - that chimps could understand some of the elements behind human art. Dubbed the Cezanne of the ape world, Congo caused a stir among artists at the time, with reactions ranging from scorn to scepticism. Picasso is thought to have framed one of Congo's works on his studio wall after receiving it as a gift. Howard Rutkowski, director of modern and contemporary art at Bonhams, previously said: "I would sincerely doubt that chimpanzee art has ever been auctioned before. I don't think anybody else has been crazy enough to do this. I'm sure other auction houses think this is completely mad." Source: telegraph.co.uk

Bonhams handout photo of a painting by Congo the Chimp. Paintings by the chimpanzee

Can Jumbo Elephants Really Paint?Intrigued by Stories, Naturalist Set out to Find the Truthby Desmond Morris Is it true that elephants are artists? Can they really paint pictures of flowers, trees and even other elephants? Are they the only animals on earth, apart from human beings, that can create pictorial images? Last summer my friend, the scientist Richard Dawkins, asked me to look at a video clip on the internet, taken in Thailand, that showed a young female elephant called Hong painting a picture of an elephant running along, holding a flower in its trunk. He wanted to know if I thought it was a fake. The internet is notoriously awash with fakes of one kind or another, but this particular video appeared to be genuine. I could hardly believe my eyes as the elephant with a paintbrush inserted in the tip of its trunk started to place lines on a large white card. Slowly, without anyone touching the animal's trunk, the image emerged. And it was an elegant image, too, something a human artist would not be ashamed of. From time to time, the elephant's keeper, or mahout, took an empty brush and replaced it with a loaded one, but that was apparently the only form of human intervention. I was amazed and puzzled by what I saw and decided that I really must find out more. Back in the '50s I had myself made a serious study of the artistic abilities of chimpanzees, but they had never achieved anything like this. My favourite chimp, called Congo, had shown remarkable abilities, creating favourite patterns of lines and then varying them from picture to picture. But all his paintings were abstract compositions. He never managed to produce a recognisable pictorial image. He had a creative ability because I never influenced the position of his lines and he himself made all the decisions about where each mark should go. He balanced his patterns and, over a long period of time, he made them more complicated, showing he contained within his brain the first germ of artistic creativity. It may have been primitive, but it was there. I was witnessing what amounted to the birth of art. If elephants could really paint flowers and trees, then they were, of course, in a different league. But I had a nasty feeling there was a catch in it somewhere, so when I was visiting Thailand this year I decided to find out the truth. I knew that Hong was living at an elephant conservation centre up in the far north of the country and that I would not have time to reach it during my brief stay. But inquiries revealed there are now at least 6 elephant centres in Thailand where painting is done. One of them, at Nong Nooch, was near enough for a brief visit. These centres originally developed because, 20 years ago, logging by elephants was outlawed in Thailand and all the domesticated elephants suddenly found themselves out of work. Their future looked bleak and there was no hope of returning them to the wild. Then someone had the bright idea of setting up elephant sanctuaries where the animals could be shown to visitors for a small fee. Out of this grew staged performances and, about 8 years ago, the painting sessions.

Tourists gasp as the animals paint detailed pictures in front of their eyes The centre I was visiting, the Nong Nooch Tropical Garden, is a large recreation park 9 miles from the thriving seaside resort of Pattaya. In addition to its exotic tropical gardens and orchid nursery, it boasts an impressive theatre where Thai boxing and highly sophisticated local folklore shows are performed. Next to this theatre there is a large, square arena for the daily elephant displays. These displays, it turned out, are far too reminiscent of old-fashioned circus acts, but they do differ in 2 important respects. First, each animal has its own personal keeper, whose whole life is devoted to his particular elephant. Second, much of the performance is designed to make the audience marvel at the skills of the elephants, rather than laugh at them as overgrown clowns. As part of the elephant show, I was able to watch 3 young female elephants painting pictures of botanical subjects and see for myself exactly how it was done. So are these endearing mammals truly artistic? The answer, as politicians are fond of saying, is yes and no. Let me describe exactly what happens. A painting session begins with 3 heavy easels being wheeled into position. On each easel a large piece of white card (30 inches x 20 inches) has been fixed underneath a strong wooden frame. Each elephant is positioned in front of her easel and is given a brush loaded with paint by her mahout. He pushes the brush gently into the end of her trunk. The man then stands to one side of his animal's neck and watches intently as the brush starts to make lines on the card. Then the empty brush is replaced by another loaded one, and the painting continues until the picture is complete. The elephant then turns towards its audience, bows deeply and is rewarded with bananas. The paintings are then removed from their frames and offered for sale. They are quickly snapped up by people who have been astonished by what they have just witnessed. To most of the members of the audience, what they have seen appears to be almost miraculous. Elephants must surely be almost human in intelligence if they can paint pictures of flowers and trees in this way. What the audience overlooks are the actions of the mahouts as their animals are at work. This oversight is understandable because it is difficult to drag your eyes away from the brushes that are making the lines and spots. However, if you do so, you will notice that, with each mark, the mahout tugs at his elephant's ear. He nudges it up and down to get the animal to make a vertical line, or pulls it sideways to get a horizontal one. To encourage spots and blobs he tugs the ear forward, towards the canvas. So, very sadly, the design the elephant is making is not hers but his. There is no elephantine invention, no creativity, just slavish copying. Investigating further, after the show is over, it emerges that each of the so-called artistic animals always produces exactly the same image, time after time, day after day, and week after week. Mook always paints a bunch of flowers, Christmas always does a tree, and Pimtong a climbing plant. Each elephant works to a set routine, guided by her master. The inevitable conclusion, therefore, is that elephants are not artists. Unlike the chimpanzees, they do not explore new patterns or vary the design of their work themselves. Superficially, they do appear to be more advanced, but it is all a trick. Having said this, what an amazingly clever trick it is! No human hand touches the animal's trunk. The brain of the elephant has to translate the tiny nudges she feels on her ear into attractive lines and blobs. And she has to place these marks on the white surface with great precision. This requires considerable intelligence and a muscular sensitivity that is truly extraordinary. So all is not lost. We can still marvel at the paintings these animals make, even if their skill is to do with muscle control rather than artistic ability. Perhaps one day, a more scientific approach will be applied to elephant painting and one of these animals will be allowed to express itself spontaneously and perhaps start making new images of her own devising, and varying them at will. If that happens, we will have to think seriously about opening an elephant art gallery. Although only 3 elephants at Nong Nooch paint pictures, there are 16 others there that perform other remarkable feats. To give just one example, two of them are able to rear up and throw a large dart through the air with breathtaking accuracy. The dart is placed in the tip of the trunk, they then tilt their head right back, take slow and careful aim, and fling the dart at a distant archery target that is covered with balloons. The target is about 60 feet away, and with its first shot, the elephant I was watching burst the balloon that was in the bull's eye position. In the wild, no elephant is ever required to make a trunk movement of this kind, or with such accuracy, so what is being witnessed here is an impressive learning ability on the part of these enormous mammals. And although playing darts is a human activity the elephants are mimicking, there is nothing demeaning in the act. It does not make the elephants look like clowns, but rather reveals to us their muscular brilliance and adaptability. Unfortunately, not all the performances in the Nooch elephant show are demonstrations that increase our respect for elephants. An elephant riding a tricycle, for instance, may be clever, but it appears ridiculous. Instead of looking magnificent, the animal looks silly. The organisers of Thai elephant shows do not seem to have caught up with the change in attitude towards performing animals that has swept through the western world in recent years. As a zoologist, I have to admit that I deplore comic acts of this kind, acts that do little more than exploit the cooperative nature of these huge mammals. If they wished to do so, they could easily kill their mahouts with a single blow, but for some reason they seem content to play along and entertain their audiences. It is up to the designers of these shows, in the future, to become sensitive to the fine line between a vulgar circus act that demeans the animals, and a serious demonstration of skill and intelligence that increases our admiration for them. With a little ingenuity, it should be possible to present a whole elephant show that does nothing but amplify the high regard that we now have for these extraordinary animals. As I mentioned, one of the most remarkable aspects of elephant behaviour is just how helpful they are. And I am extremely grateful to them for their level of co-operation. Organisers of the Nong Nooch elephant show discovered that I was there to make a special study of them and asked if I would like to participate in the finale of the show. I declined, but they insisted that I would not have to do anything, just lie on the ground and let one of the elephants give me a massage. It crossed my mind that, if I did agree, here was a test in which, if anyone was going to look silly, it would be me rather than the elephant. And I would be helping to demonstrate to the audience just how restrained and delicate the giant animal could be. After all, a massage performed poorly by an elephant's foot could see me ending up in intensive care in a Thai hospital. An Englishman abroad hates to look like a coward in such situations, so I allowed myself to be taken into the centre of the arena, where I was instructed to lie down on a piece of matting. A large cloth was draped over me to protect my clothing and out of the corner of my eye I saw one of the largest elephants approaching with what I swear was an eager gleam in her eye. She proceeded to give me my massage, first with her trunk and then with one of her front feet. I experienced what hospitals euphemistically call "a certain amount of discomfort", because gentle as the elephant was, bless her, she was being encouraged by her mahout to overdo the massage in order to amuse the audience. It was at this point that I became acutely aware of the subtle distinction between hamming it up for circus laughs and the scientific demonstration of an elephant's true capacity to restrain itself from squashing a large Englishman beneath her foot. Before I allow myself to get involved again, I think I will await the hoped for evolution of these Thai elephant shows into a more scientifically controlled demonstration.

Elegant: A painting of an elephant by Hong the elephant Source: dailymail.co.uk 22 February 2009 "Human-Brained" Monkeys

Monkey magic ... one day you really may be able to talk to the animals, if a human/monkey "chimæra" develops a human-like brain. by Nick Buchan Scientists have been warned that their latest experiments may accidentally produce monkeys with brains more human than animal. In cutting-edge experiments, scientists have injected human brain cells into monkey fœtuses to study the effects. Critics argue that if these fœtuses are allowed to develop into self-aware subjects, science will be thrown into an ethical nightmare. An eminent committee of American scientists will call for restrictions into the research, saying the outcome of such studies cannot be predicted and may in fact produce subjects with a "super-animal" intelligence. The high-powered committee of animal behaviourists, lawyers, philosophers, bio-ethicists and neuro-scientists was established 4 years ago to examine the growing numbers of human/monkey experiments. These procedures, known as "human-primate chimeras", involve the combination of human and monkey cells, tissue and DNA to observe any effect and examine the possibility that such combination could actually exist. Chimeras are mythical monsters from Greek literature, which combined various bodyparts from lions, goats and snakes. This team will soon publish its conclusions in leading journal Science. In the report the committee will address such unsettling questions as whether introducing human cells into non-human primate brains could cause "significant physical or biochemical changes that make the brain more human-like" and how those changes could be detected. The committee will also examine how detectable differences in the monkey's brains, for example emotional or behavioural changes, or if the monkeys developed "self awareness," could be measured - and dealt with. "What we were trying to do was anticipate - recognising that if science were to take that path there might be some different kinds of moral challenges." said committee co-chairman Dr Ruth Faden, a professor in biomedical ethics. Source: news.com.au 11 July 2005

Many years ago (1984) I read a science fiction novel by an unusual author named John Crowley called Beasts that dealt with this possibility. The animal/human blends who might be born would not otherwise have the chance to live. Would they prefer a chance at life than never to have lived at all? (I expect so.) What, exactly, is the ethical nightmare the author speaks of? That you couldn't eat these creatures or kill them at will? That they might want to vote? To be covered by Medicare? I personally think this would teach us a lot about what it means to be "human". Or "animal".

Gorilla Dies in Cincinnati after Spending Years at Pensacola Zoo

Pensacola - Colossus, the magnificent, 500-pound silverback gorilla who awed visitors at The Zoo and Botanical Gardens near Gulf Breeze has died at the Cincinnati Zoo. The 40-year-old gorilla was caught when he was a baby and grew up in private zoos with no other gorillas. He never learned breeding behaviour. Colossus arrived at The Zoo near Gulf Breeze in 1988 after spending more than 20 years caged indoors at Henson's Animal Park in New Hampshire. The ape had never felt grass or seen another gorilla until he moved to the Gulf Breeze facility. He quickly became a star attraction at The Zoo, where he spent several years with a lone female - but he never sired an offspring. Colossus was transferred to Cincinnati in 1993, where he lived with a group of three females. Again, he never mated. Today, fewer than 75 thousand western lowland gorillas survive in the wild, and only 346 live in captivity in North America. Source: wpmi.com 14 April 2006 © The Associated Press all rights reserved photo credit Cincinnati Zoo

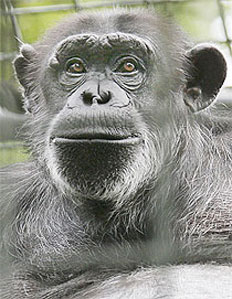

It's No Tea Party for Janieby Tim Hume

"What's she doing in there?" a boy asks his mother. "Just sitting around, getting old ... poor thing," comes the response. "Come on, let's go." It's all a far cry from her heyday, when, with Bobby, Josie, and Minnie, who died in 1964, Janie played to packed houses as a star of the chimp tea parties of the 1950s and '60s. The hand-raised quartet, who arrived in Auckland from London's Regent's Park Zoo in 1956, would dress up in Sunday best, pull faces, fling scones and generally goof off to the delight of the crowd. Times changed, the chimps grew too big to safely continue with the schtick, and the parties fell out of favour. The faded celebrities found these wilderness years difficult. "They became very aggressive," says curator Maria Finnigan, who has known Janie since the early 1980s. "It's the same as a child having incredible amounts of attention and then it just stops." Efforts to integrate the trio with the regular chimpanzee community failed, because they did not understand the rules of chimp society. They hated the natural-style habitat of the main enclosure, preferring the roofed security of the concrete den where they lived together. In a reversal of chimp social order, Janie, a moody, capricious prima donna, always dominated the trio. "She's just bolshie, she's an interesting chick," says Finnigan. "If Janie did understand chimp society, she would have respected the fact Bobby was the male. She used to allow him to display but if she got sick of it she would just go up and tell him to stop. Her dominance meant they had a dysfunctional sex life and never bred. He would have copped a whack if he tried it on when she didn't feel like it." Finnigan says despite the loss of Bobby, Janie does not appear unhappy in her solitude, as she had always been self-reliant. "She doesn't exhibit the behaviours she would display if she was depressed: self-plucking, general agitation." Six months ago, Janie was given a toy cellphone which immediately became a prized possession, and something of an emotional security blanket. She constantly carries it with her, cradled between her thigh and her sizeable potbelly. "She's a big lady," says Finnigan. "But the one thing you don't do with Janie is call her fat. She probably had a keeper at one stage who called her fat a little too often, and she gets a little distressed by the word." Finnigan says Janie's health is "definitely in decline"; she is in worse condition than Bobby was when he died. Her wellbeing is constantly monitored. Chimps live to about 45 in the wild. While Janie's treatment by humans has given her life the contours of a Hollywood tragedy, Finnigan takes comfort from the fact they're giving her a good retirement. "It's a shame. She turned out to have such a different personality because of this early intervention. It's an example to everyone; let's never go back to those times." Source: stuff.co.nz 9 April 2006 photo credit Sunday Star-Times

She Needed a Hand...

Photo by William West

Dolphins "Know Each Other’s Names," Whistles Used for Individual Recognitionby Jonathan Leake Dolphins may be closer to humans than previously realised, with new research showing they communicate by whistling out their own names. The evidence suggests dolphins share the human ability to recognise themselves and other members of the same species as individuals with separate identities. The research, on wild bottlenose dolphins, will lead to a reassessment of their intelligence and social complexity, raising moral questions over how they should be treated. The research was carried out by Vincent Janik of the Sea Mammal Research Unit at St Andrews University, who has found bottlenose dolphins to be among the animal world’s quickest learners of new sounds. He said: "Each animal develops an individually distinctive signature whistle in the first few months of its life, which appears to be used in individual recognition." The research has its origin in the 1960s when dolphin trainers first noticed that captive animals each had their own personal repertoire of whistles. This prompted speculation that dolphins had their own language and might even have individual names. However, the theory was controversial among whale and dolphin researchers, and until now, there had been no means of testing it. Janik’s work was based on a group of dolphins living in Sarasota Bay, Florida, who have been studied for more than 30 years. Over that time researchers have built up a detailed picture of individual dolphins, their family ties and their social interaction. They have also made extensive recordings of the noises made by individual dolphins and isolated the sounds thought to be their signature whistles or names. In the study some of the Sarasota Bay animals were corralled in a net. The researchers then played synthetic versions of the signature whistles of other dolphins through underwater loudspeakers to see if they would evoke a response in the captive animals. The use of synthetic whistles ruled out the possibility that the animals might simply be recognising the sound of each other’s voices. They found that dolphins responded strongly to the whistles of their relatives and associates while generally ignoring those of dolphins to whom they had no link. Janik said: "Bottlenose dolphins are the only animals other than humans to have been shown to transmit identity information independent of the caller’s voice."

A bottlenose dolphin swims with a youngster. The findings are supported by other authorities. Denise Herzing, research director at the Wild Dolphin Project at Florida Atlantic University, said it was already clear that many of the 77 known cetacean (whale and dolphin) species had rudimentary languages. "We know that dolphins’ brains are nearly as large and complex, relative to body size, as those of humans. They have evolved to be intelligent and that implies being able to communicate," she said. Dolphins may, however, be just the first of many species where individuals are found to have their own names. Other researchers have already found evidence for highly developed language skills in parrots, crows and primates. Great apes, such as chimpanzees and orang-utans, have been a popular subject for research because they are so closely related to humans. Their limited vocal apparatus means they cannot speak but researchers at Georgia State University have taught chimpanzees to communicate in English via computers equipped with customised keyboards and voice synthesizers. The African grey parrot is another renowned linguist, able not only to learn words but to use them in the right context. Even some rodent species may have developed a rudimentary language. Con Slobodchikoff of Northern Arizona University recently found that prairie dogs, a large rodent found in the western United States, shared a language of at least 100 words. Donald Broom, professor of animal welfare at Cambridge University, said species living in large groups all had advanced communication skills. "They have a complex social structure where they have to live with others, negotiate friendships and find mates. If dolphins are using names I expect we will find the same in other species with similar lifestyles." Jonathan Leake is the Science editor Source: timesonline.co.uk The Sunday Times 7 May 2006

Pyow Pyow Pyow ... Hack Hack Hack Hack! Let's Get out of Here (in Monkey Talk)by Mark Henderson It seems that human beings are not the only ones who are able to string sentences together. Monkeys are able to string together a simple "sentence" according to research that offers the first evidence that animals might be capable of a key feature of language. British scientists have discovered that the putty-nosed monkey in Nigeria sometimes communicates by combining sounds into a sequence that has a different meaning from any of its component calls, an ability that was thought to be uniquely human. Although many animals communicate with one another using calls that have a particular meaning - usually a warning signifying the presence of a certain predator - none has been known to combine these alarm calls into sequences similar to those of human language. The findings suggest that the rudiments of syntax, a basic component of human language, may be more widespread among primates than is generally thought, and could ultimately shed light on the evolution of this most distinctly human of traits. The putty-nosed monkeys, Cercopithecus nictitans, of the Gashaka Gumti National Park, have two main alarm call sounds. A sound known onomatopoeically as the "pyow" warns other animals against a lurking leopard, and a cough-like sound that scientists call a "hack" is used when an eagle is hovering near by. Kate Arnold and Klaus Zuberbühler, of the University of St Andrews, have now observed the monkeys using these sounds in a new way. A particular sequence of pyows and hacks appears to mean something entirely different. The monkeys live in groups consisting of a single adult male accompanied by several adult females and their young. When the male utters this "sentence", consisting of up to three pyows followed by up to four hacks, it seems to be a command telling others to move, generally to find safer, less exposed terrain. They use the signal not only when predators are around, but also during ordinary activities such as foraging. It seems to mean "let’s get out of here". The research is published in the journal Nature. Dr Arnold said: "These calls were not produced randomly and a number of distinct patterns emerged. One of these patterns was what we have termed a pyow-hack sequence. This was either produced alone or inserted at certain positions in the call series. Observationally and experimentally we have demonstrated that this sequence serves to elicit group movement in both predatory contexts and during normal day-to-day activities such as finding food sources and sleeping sites. The pyow-hack sequence means something like ‘let’s go’ whereas the pyows by themselves have multiple functions and the hacks are generally used as alarm calls. The implications are that primates, at least, may be able to ignore the usual relationship between an individual call and any meaning that it might convey under certain circumstances." Dr Zuberbühler said: "To our knowledge, this is the first good evidence of a syntax-like natural communication system in a non-human species." A separate study, also published in Nature, has shed further light on human evolution, suggesting that early human ancestors may have interbred with the forerunners of chimpanzees for hundreds of thousand years after the two species branched out from their shared family tree. A comparison of the genetic codes of humans and chimps has revealed that the split between the two probably occurred much later than is generally thought, and in a much more complicated fashion. According to previous estimates, the last common ancestor of both species lived about 7 million years ago. The genetic study, however, sets 5.4 million years ago as the most likely date for the split, and shows that it cannot have happened more than 6.3 million years ago. The analysis also indicates that after the split both branches initially interbred, before they ultimately diverged into distinct species. "The genome analysis revealed big surprises, with major implications for human evolution," Eric Lander, of the Broad Institute at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said. Source: timesonline.co.uk The Times Online 18 May 2006

For more on animals, including reptiles, crustaceans, arachnids, insects, fish, birds, pets, livestock, rodents, bears, primates, whales and Wellington's waterfront, click "Up" below to take you to

the Table of Contents for this Animals section. |

Animals

Animals Animation

Animation Art of Playing Cards

Art of Playing Cards Drugs

Drugs Education

Education Environment

Environment Flying

Flying History

History Humour

Humour Immigration

Immigration Info/Tech

Info/Tech Intellectual/Entertaining

Intellectual/Entertaining Lifestyles

Lifestyles Men

Men Money/Politics/Law

Money/Politics/Law New Jersey

New Jersey Odds and Oddities

Odds and Oddities Older & Under

Older & Under Photography

Photography Prisons

Prisons Relationships

Relationships Science

Science Social/Cultural

Social/Cultural Terrorism

Terrorism Wellington

Wellington Working

Working Zero Return Investment

Zero Return Investment

Chantek asks Lyn what's wrong with her hand, which has a scratch on the knuckle. I did it

cleaning, she tells him, and he makes a grimace of sympathy, then asks to touch and kiss it... Chantek has had surgery recently on his laryngeal flap, the long black fold under

the chin that makes orangs look like some kind of colonial barrister, and she asks him how he's feeling, if the suture's healing okay. Yes, says Chantek, he's fine. He

has missed Lyn and wants to play ball. Oh, and there's poop on the other side of the habitat, presumably left there by his companion, Sibu; it's dirty and he'd like it removed

(Chantek uses a toilet)... Chantek calls himself an Orangutan Person. Presumably this term would refer to any orang who'd been acculturated and given

language. Untaught orangutans, like his cagemate Sibu, he's given the rather snide name of Orange Dog. He uses words plus gestures to speak: He might tell Lyn "I you

talk," indicating the other side of the cage, when he wants privacy from me - from my keen and almost predatory listening - as he does several times when I'm there. (He insists

on privacy to discuss the poop situation.) ... "Sad," Chantek says when ... Lyn leaves (Antonetta).

Chantek asks Lyn what's wrong with her hand, which has a scratch on the knuckle. I did it

cleaning, she tells him, and he makes a grimace of sympathy, then asks to touch and kiss it... Chantek has had surgery recently on his laryngeal flap, the long black fold under

the chin that makes orangs look like some kind of colonial barrister, and she asks him how he's feeling, if the suture's healing okay. Yes, says Chantek, he's fine. He

has missed Lyn and wants to play ball. Oh, and there's poop on the other side of the habitat, presumably left there by his companion, Sibu; it's dirty and he'd like it removed

(Chantek uses a toilet)... Chantek calls himself an Orangutan Person. Presumably this term would refer to any orang who'd been acculturated and given

language. Untaught orangutans, like his cagemate Sibu, he's given the rather snide name of Orange Dog. He uses words plus gestures to speak: He might tell Lyn "I you

talk," indicating the other side of the cage, when he wants privacy from me - from my keen and almost predatory listening - as he does several times when I'm there. (He insists

on privacy to discuss the poop situation.) ... "Sad," Chantek says when ... Lyn leaves (Antonetta).

In a drab concrete room in an Auckland suburb, a former child star is seeing out her autumn years in tragic

fashion. Crotchety, socially maladjusted, as bloated as Elvis in his twilight, Janie, the last of Auckland Zoo's famous tea party chimps, cuts a sorry sight. Since the death of her life

companion Bobby and relocation of the zoo's main chimpanzee colony to Hamilton in 2004, the 52-year-old has become the only chimpanzee in Auckland. Battling diabetes and a heart condition, she

whiles her days away alone in her enclosure, with a tv and reading material - Monkeys and Apes - for stimulation, and a cellphone that never rings. The reaction from passersby is invariably

one of pity.

In a drab concrete room in an Auckland suburb, a former child star is seeing out her autumn years in tragic

fashion. Crotchety, socially maladjusted, as bloated as Elvis in his twilight, Janie, the last of Auckland Zoo's famous tea party chimps, cuts a sorry sight. Since the death of her life

companion Bobby and relocation of the zoo's main chimpanzee colony to Hamilton in 2004, the 52-year-old has become the only chimpanzee in Auckland. Battling diabetes and a heart condition, she

whiles her days away alone in her enclosure, with a tv and reading material - Monkeys and Apes - for stimulation, and a cellphone that never rings. The reaction from passersby is invariably

one of pity.